If you ever wondered what your family members or roommates do all day when they are not home, by now you probably know. We can sit in the living room and watch our housemates struggle over homework or conduct a meeting at the dining room table, view unobstructed. In spending so much time in such close quarters, the question begins to be asked: Why do our homes look the way they do in the first place?

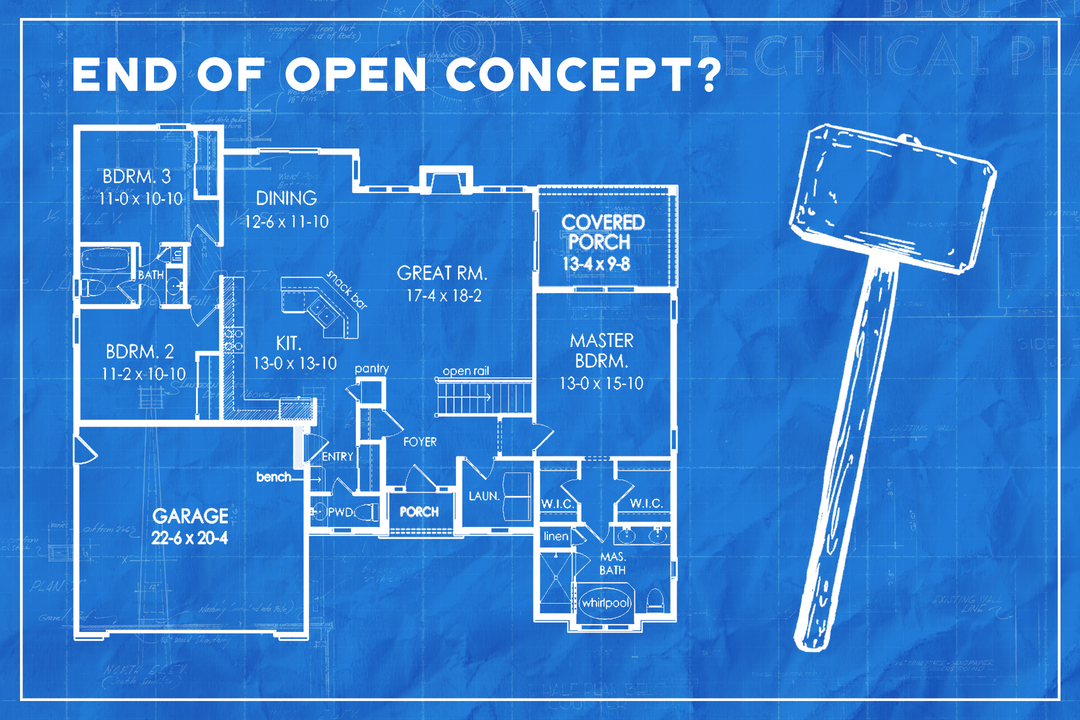

Open-concept homes have many rooms, such as a kitchen, living room and dining room, that all flow into each other, not clearly separated by walls or doors. They have been popular in America in recent years. Initially, the open-concept became popular on the claim that it would allow family members to spend more time together by doing different things while remaining in each other’s proximity, as described by Robin Abrams, head of architecture at NC State.

“I think it reflects changing lifestyles, particularly where the homemaker (male or female) doesn’t want to be stuck in an enclosed kitchen but can participate in the life of the family while preparing meals and cleaning up, etc,” Abrams said in an email. “It represents a general breaking down of social constructs from before the 20th century and was made possible by innovations in construction technology.”

The open-concept house popularized the idea of a family sitting together in one common area while doing separate activities. However, as people have been forced to spend more time together, the concept has faced newfound criticism due to the lack of privacy it grants. Abrams said architects are already seeing trends of people requesting areas of privacy, such as home offices.

“Yes, it is pretty difficult to work from home in a one-bedroom apartment, so we are beginning to see more elaborate home offices incorporated into plans, and also we now see the necessity of having semi-private open space (balcony, patio) attached to every dwelling unit,” Abrams said in an email.

According to The Atlantic, the combination of the open-concept house and the pandemic have also weakened this idea, as many complain that a house without walls lays bare household inequities.

According to Karey Harwood, associate professor of women and gender studies at NC State, the inequity that exists inside the home is often euphemized as “The Second Shift,” a term popularized by feminist Arlie Russell Hochschild. This forced idea of shelter-in-place has prompted even more parents to take on intensive “second shifts” of childcare and housework, alongside their professional jobs, and the majority of such work has often fallen to women within the home.

“The unpaid labor that women often do that has only doubled or quadrupled during the pandemic,” Harwood said. “Women are doing all that they normally do and also helping kids with homeschooling and also cooking every meal, whereas in normal times the family would go out.”

In reflection of her own situation, Harwood said she was thankful to have an office space of her own outside of her home throughout the pandemic, noting her non-tenured colleagues are not always as lucky.

“Sometimes [non-tenured faculty] are combined together; sometimes they share an office, or they take turns, or before the pandemic they might both be there at the same time,” Hardwood said. “I think that’s unfortunate because, in this type of work, I think it’s important to concentrate and have quiet space, and how it’s designed often does say a lot about the values of the institution and can reveal points of inequity and who gets to have space of their own and who doesn’t.”

Abrams also elaborated on this theme of the societal attitudes that are often embedded within physical spaces

“Well, there is a lot to say about architecture, but in relation to everything going on today, including COVID and political tension, we are perhaps more aware than ever of disparities in living environments, and how those affect performance in the workplace and at school,” Abrams said in an email.