The Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies has put together “Turath,” a digital exhibition to understand and celebrate the history of Arab American contributions to art, literature and press. The exhibit is the culmination of a year of attempts at understanding the historical impact of race in America as well as a divisive conversation about immigration for at least the past three presidencies.

Headed up and curated by Akram Khater, the director of the Khayrallah Center and a history professor; Marjorie Stevens, senior researcher; Mandy Paige-Lovingood, an NC State public history Ph.D. candidate; and Samantha Aamot, an NC State public history M.A. candidate, the exhibition marks the centennial celebration of the re-establishment of al-Rabitah al-Qalamiyya, an early Arab American literary society, in 1920. According to Stevens, the exhibition focuses on Arab Americans between 1880 and 1940.

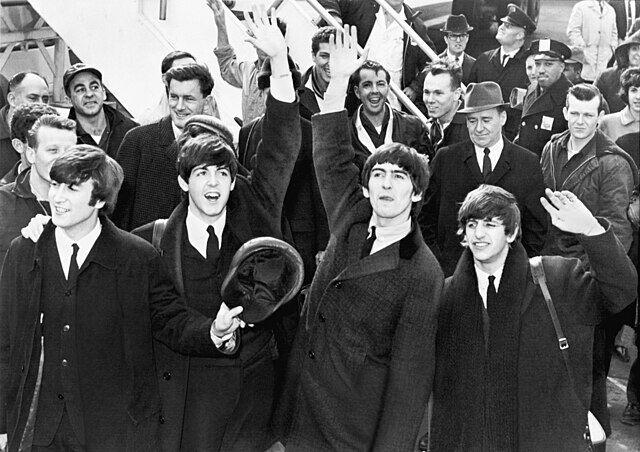

“The time period, 1880 to 1940, coincides with the first major wave of Arab immigration to the U.S.,” Stevens said. “During this period, Arab immigrants drew from their experiences in the Middle East and their new experiences in America, the Mahjar, [a literary movement based on the Arab American experience in America,] to usher in a new wave of Arab culture. This was especially true in literature, where authors in the U.S., such as Kahlil Gibran and Ameen Rihani, incorporated Western Romanticism in their poetry and novels, and used literature as a platform for gender, religious and political reform.”

The exhibition has five individual sections — art, literature, music, performance and press — that work to piece together the lives of a group of people who have largely been ignored or reduced to two-dimensional stereotypes in conventional historical studies.

“I think what you find with Arab Americans as an immigrant community is they really have been kind of kept out of the history of America, and whenever they appear, either in culture or political discourse — they never appear in history books — they appear as the other,” Khater said. “They appear as people who are alien to America and its values, at best, and more often than not they appear as the kind of menacing other, the terrorist, the violent extremist. They certainly appear as if they just arrived here yesterday, after 9/11.”

Khater and his team wanted to break this stereotype and document the rich history of Arab Americans and their impact on American society and culture. This led to the title, “Turath.” Turath is an Arabic word meaning heritage that Khater feels represents this project as a whole.

“A lot of times, especially young Arab Americans, find themselves under attack by the representation they are given about who they are as a community,” Khater said. “In a way, it’s to give them a sense of, ‘Look, there’s this richness to who you are.’ To give them a sense of roots — deep roots — that are positive, engaging and that hopefully will encourage them to go on their own journey and create new heritage moving forward.”

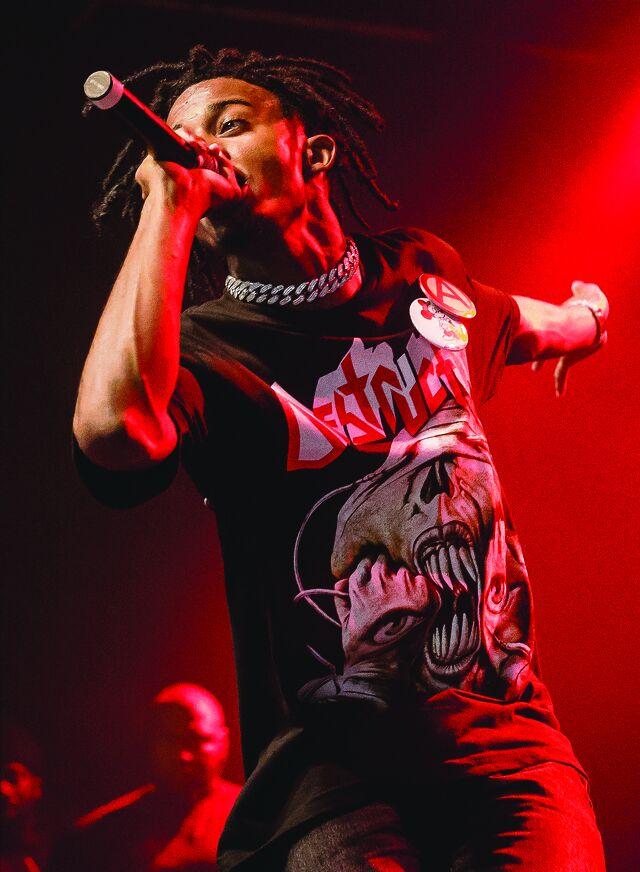

As part of this exhibition and to further this idea of a cultural lineage for Arab Americans, the Khayrallah Center will be hosting five webinars with contemporary Arab American artists who use their cultural history in the creation of their art. The first will be held on Jan. 13 at 7 p.m. and will feature Syrian American hip hop artist, designer and activist Omar Offendum. Artists featured at future webinars will include Lebanese American painter Helen Zughaib, Sudanese American poet Safia Elhillo, Lebanese American novelist Rabih Alameddine and Lebanese American pianist and composer Tarek Yamani.

According to Stevens, this exhibition was originally supposed to be a physical exhibit that toured museums in New York City, Houston, Detroit, Los Angeles and Raleigh. However, due to the pandemic, the exhibition was moved online for safety purposes. Khater said this kept them from having to worry about whether or not the museums had enough space or the right kind of space for the exhibit and allowed them to include more interactive elements.

“We could include more video interviews, more images, and more detailed and layered text delving into topics,” Stevens said. “Instead of developing physical interactives, we worked with a computer programmer to develop three digital interactive games. During the pandemic, we could not travel or conduct in-person interviews with experts, so we used a combination of high definition audio/visual devices and Zoom to conduct socially-distanced interviews. The entire process was a great learning experience in how to use technology to our advantage and adapt effectively in trying times.”

Overall, Khater hopes this exhibit sheds new light on an old conversation that is rooted in hate and ignorance.

“When we were doing this research, we were very conscious of the moment in which we were doing the research,” Khater said. “All the rhetoric and very virulent at times anti-immigrant rhetoric that we see coming from certain corners of America. That was a very vital element of how we looked upon this through that particular lens. That’s the power of public history.”