According to a recent Technician news article, NC State has enrolled, for the first time in its history, a freshman class with a roughly equal proportion of those who identify as men and women. Without a doubt, this is a promising development for the university, which began as a male-only institution and has been disproportionately male ever since.

Gender equality at NC State is something we should all be excited about. When the proportion of women and men is not roughly equal, it indicates a systemic bias in favor of one group succeeding academically to the point of attending higher education. Historically, and still to the present day, that bias has worked in favor of men, granting them the prestige and economic advantages relating to a university education.

Not only is this fundamentally unfair, it also puts our society as a whole at a disadvantage by excluding the intelligence, hard work and creativity of half of the population from reaching its fullest potential. A large community of innovators helps spur innovation, so we must remain alert to any societal influences that would reduce the size of that community.

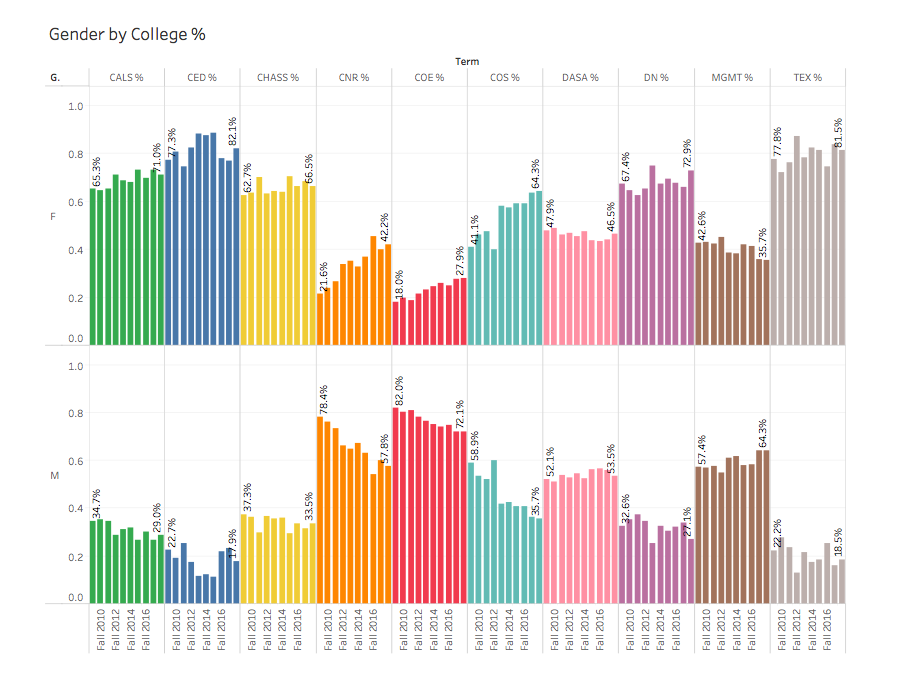

As promising as these new numbers are, looking more closely at them reveals details that aren’t quite as rosy as the big picture. In the College of Engineering, for instance, women make up just slightly more than a quarter of the population, whereas in the College of Education, men don’t even compose a fifth of the population.

This huge discrepancy between the sexes is one of the key factors contributing to the gender pay gap. According to Money magazine, while average engineering graduates earn around $65,000 a year, education majors will earn just over half of that, at $35,000 a year. Consequently, when we see a huge number of male engineers and female educators, it inevitably leads to a stark difference in pay.

There are a number of other issues with celebrating this statistical milestone too vigorously — including, but not limited to, the intersection between gender and race or the failure to account for gender-nonconforming students in these data — but all in all it demonstrates a commitment on the part of the university to ensuring an open environment for all students.

The upside of these finer details is that they provide a road map for how to work towards a deeper gender equality at NC State.

Programs such as WISE must continue to provide support for women in male-dominated fields. Male students in these disciplines should monitor the behavior of themselves and their peers to ensure they aren’t delegitimizing or excluding female students. We as a society must collectively fight the stereotypes of the straight, white, male engineer to prevent sending the wrong message to people of other identities who have talents in science and math.

On the flip side, we must also work to remove the stereotypes surrounding “pink-collar” jobs, such as primary school educators. We should encourage men to break from rigid norms of “maleness” and feel free to express personality traits traditionally attributed to women, like emotional sensitivity, that lend themselves to such work. Finally, society could stand to reconsider the value of pink-collar jobs to better account for their often central roles in modern life.

We should be encouraged by the progress we’ve made since 1899, when NC State first opened its doors to female students, but we must not fall into complacency, thinking that we’ve achieved true gender equality. This goal is a worthy one, and we have the tools to achieve it, but we will only be successful if we commit ourselves to working for positive change in our community.