When Rachel Powell began teaching SOC 304, Women and Men in Society, in the fall semester of 2013, she wanted to create a classroom environment that broke down the barriers of patriarchal language to create an inclusive and nonsexist learning environment.

“We associate men with power when we use words like ‘chairman’ instead of ‘chairperson,’” Powell said. “It’s not just anyone in an organization, it’s someone at the top, it’s the way we demarcate a male nurse or a female doctor. We’re attaching gender to a particular status.”

At the start of the semester, each student received a document written by Powell, a sociology graduate teaching assistant, titled “Language Matters! Sensitivity and Inclusion Tips” describing appropriate and inoffensive ways to talk about gender, sexuality and ethnicity.

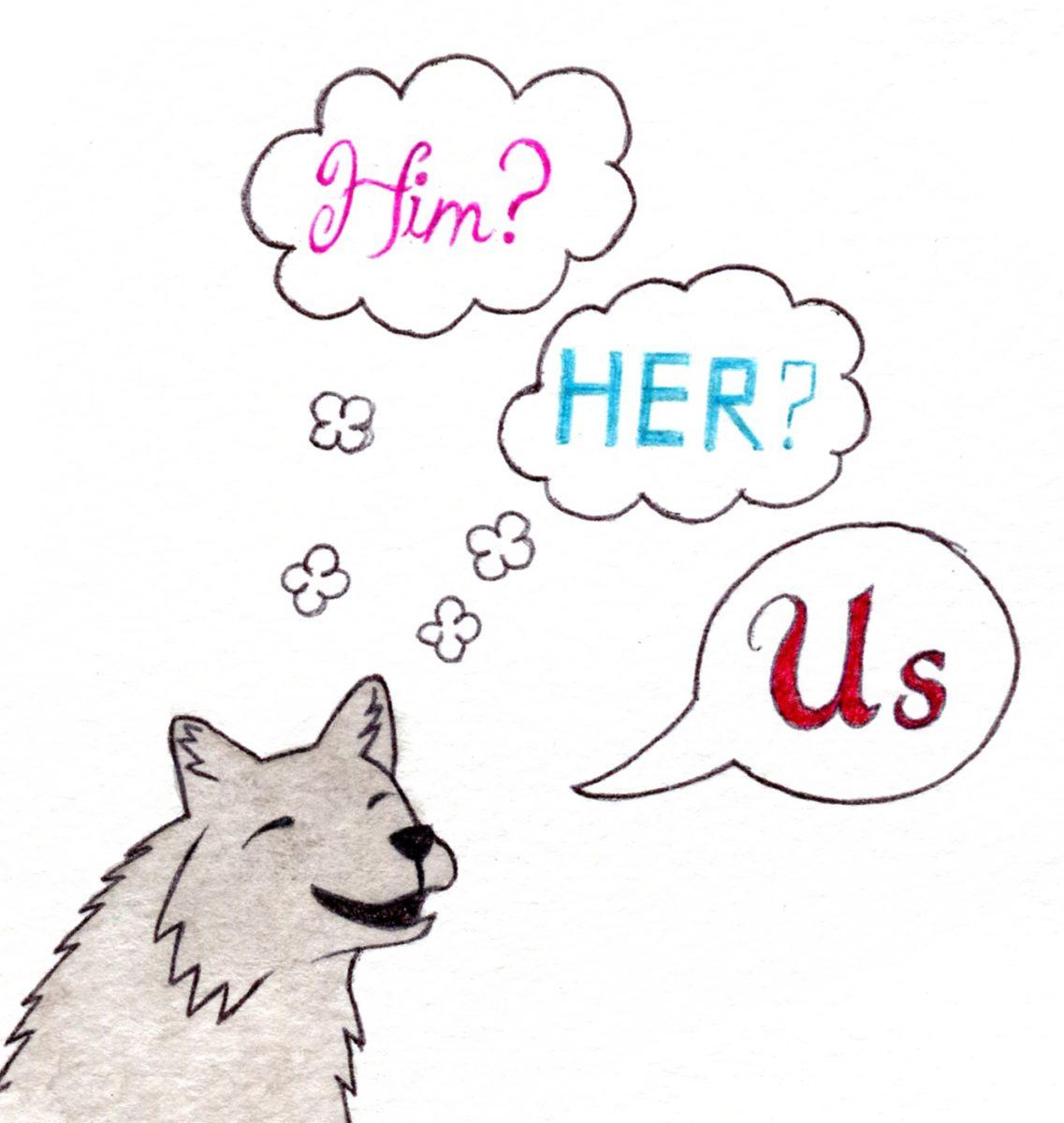

For example, she discourages the use of gender-specific pronouns and outdated terms such as “hermaphrodite” or “colored people.” She suggests words such as “partner” to replace “husband/wife” and “boyfriend/girlfriend” in order to avoid language that implies gender or marks a status.

Though the new language in Powell’s class could be something to get used to, it seemed to positively affect class discussion, according to Marshall Chappell, a senior studying sociology, who took the course last fall.

“I think Rachel [Powell]’s lack of gendered language aided discussion by not alienating anyone from it, which created an environment where everyone could feel included and comfortable to contribute regardless of gender identity,” Chappell said.

When language was misused during class discussions, it was not punished, but instead the class would stop and discuss the word or phrase, its origins, what it means, why it is important to avoid it and find a suitable alternative.

“Students were reaching for language that wouldn’t offend their classmates, but not knowing what to replace it with,” Powell said. “It was a matter of integrating male generics into instructions on how to have a conversation using language that was inoffensive and got to the point.”

Powell’s interest in gender studies stemmed from the intersection of family and inequality in sociology. She said she learned a lot about issues for women when she worked at an abortion clinic and realized that despite our advances in gender equality, these issues still persist. She also found that gender issues are especially relevant on college campuses where usually over half the population is made up of women.

“There’s not nearly as much resistance now to the idea that women should have equal access to reproductive healthcare, to the idea of gay marriage,” Powell said. “Ten years ago, it would have been a different conversation in the classroom.”

During the first semester, students were not as receptive to these tips as Powell had hoped, so at the start of the second semester, she put more emphasis on the importance of the document by discussing it with the class and allowing students to personalize it according to their own preferences and experiences.

As new words become popular and the meanings of old words changed, Powell said she saw the necessity for occasional revisions and edits. For instance, the first version of the document included how to address Native Americans. A student in Powell’s class pointed out that this group preferred to be called American Indian or “part of a nation.”

“Getting that feedback from students, and growing the document and changing it over time has helped because now it’s even more accessible,” Powell said. “The attitude of the students has improved each time as they’ve gotten to own the document and put in their input.”

As an English major, Claire Healey, a 2015 alumna of NC State, noticed the dichotomy of language even before taking Powell’s class during the fall 2015 semester. One example that she said stood out to her was the big orange signs at construction sites that say, “Caution, men working.” In Powell’s class, she became more cognizant of students’ efforts, as well as her own, to use gender-neutral language.

“People were very conscientious about what they were saying because there are touchy subjects, and you never wanted to offend anyone, so I think that people were more thoughtful about the specific words they used when we were having a discussion,” Healey said.

At first, Powell was worried that students would be resistant to the idea of integrating non-gendered language into their everyday lives, but she has been impressed with how willing they have been to consider these ideas. She said she has found that most students, including Healey, were engaged and open-minded.

“This class certainly reinforced my desire to be more aware of how I speak about things and to understand how a lot of times people’s ideas about gender are created based on gendered language,” Healey said. “It has made me want to be more inclusive and more considerate when I choose words.”

Chappell said he noticed a similar effect as Healey did after he took SOC 304 with Powell. He specifically noted how he could utilize this kind of inclusive language in future discussion.

“The class reaffirmed and deepened my pre-existing understanding of gender and gave me the tools to better participate in discussions about important gender issues,” Chappell said.

Powell said she believes that language should be all-inclusive, non-offensive and move toward gender-neutrality, but that we will probably not see the demise of sexist language.

“Our language is so ingrained in how we think and there are real obstacles standing in the way, but that doesn’t mean that we aren’t making progress,” Powell said. “It just means that we have to be aware of the fight in front of us.”

- Print edition

- Sex: It’s not that weird

- Playlist: ‘Let’s talk about sex’

- Amazon’s top 10 best-selling sex toys for online shoppers

- Sexual com class to host ‘kinky science fair’

- NCSU provides resources to promote sexual health

- GLBT Center offers safe space, counseling for all

- Greek Life works to prevent sexual assault through education

- Professor Crane-Seeber talks male feminism, rape culture

Opinion columns: