Graphic by Devan Feeney

Go to college for four years directly out of high school, get your diploma and immediately join the workforce. That has been the status quo and the supposed key to social mobility and financial wellbeing.

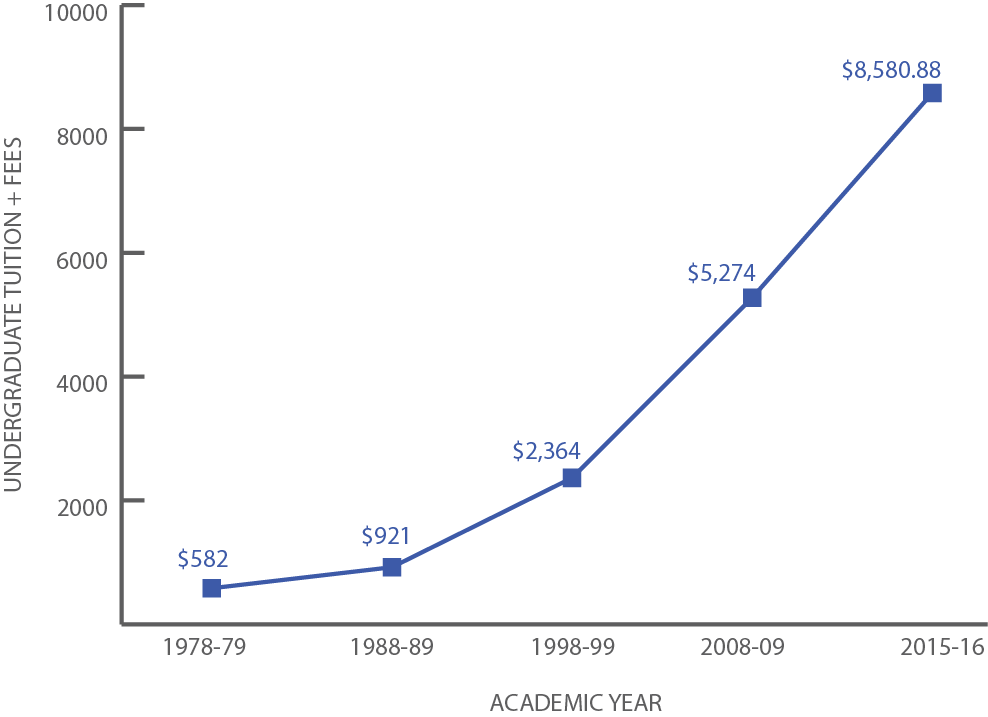

However, rising tuition costs over the past 30 years have made it harder and harder for Americans to uphold this golden standard.

Tuition prices at American universities have increased 600 percent between 1980 and 2010, more than any other product or service, according to The Atlantic. Even if a student were to work full time at minimum wage, they would not begin to cover the price of tuition, fees and textbooks.

At NC State, more than 60 percent of undergraduate students rely on financial aid to help pay for tuition, according to Maria Brown, director of the Cashier’s Office.

However, the university ranks fairly well compared to the national average of student loan amounts and default rates, according to Brown. The average loan debt for an NC State student is around $17,000, compared to the $35,000 national average. The average default rate for NC State students is 3.4 percent, compared to the 17 percent national average default rate.

Tuition hikes

Between the 2004–2005 academic year and the 2015–2016 academic year, in-state tuition has nearly doubled from $3,205 to $6,220. In the 1977–1978 academic year, tuition was a mere $364, according to the Cashier’s Office.

“It’s going up because things cost more, and we’re getting less from the state,” Brown said. “There is a conscious level to keep tuition affordable. There’s not this bigger person who says, ‘We still want students to pay this crazy amount.’ But the reality is we still want you to have a good education.”

For the 2015 – 2016 academic year, the North Carolina General Assembly cut $18 million from NC State’s funding in what is called a “management flexibility reduction.” Next year, the General Assembly will cut another $28 million from the university’s budget, according to Andrea Poole, associate vice president for finance & university budgets for the UNC System.

These reductions are cuts from the legislature to higher education, in which the Board of Governors must decide how each campus in the UNC System will take the hit, Poole explained.

“It doesn’t allow us to cut specific campuses, but they tend to be smaller campuses, and it doesn’t allow us to cut certain programs,” Poole said. “At NC State, we’re not allowed to cut the Future Farmers of America program.”

Yong Park, a senior studying sport management, said the increasing tuition creates a huge burden.

“You have to either take out more loans or work longer hours to make up the money,” Park said. “It can also affect your life as you can’t go out as often even though you’re trying to maximize your college experience.”

John Bradner, a senior studying economics, also described his experience with rising tuition.

“Looking at the cost go up just in the time I have been at State is staggering,” he said. “Every time I see the e-bill increase, it makes me thankful for a single-parent father who has invested in my education since I was born.”

In the past decade, NC State has received management flex reductions of $161 million, Brown said.

This past year, with the management flexibility reductions, the General Assembly appropriated $409 million to NC State, which provided $17,147 toward the cost of education toward each in-state student.

To maintain operations and its budget, NC State must raise tuition in order to compensate for the cuts to higher education. However, they are necessary, according to Davis.

“We have to keep pace with the needs and desires of college students while maintaining quality education,” she said.

Low-income students

Statistically, the hikes in tuition hit minority and low-income students the hardest. However, the university takes pride in closing the gap between enrollment and graduation rates for majority and minority students, according to Mary Lelik, senior vice provost for the Office of Institutional Research and Planning.

“One of the things that has happened over time is that there’s been a gap in the graduation rate between minority and majority students. The university is proud of the fact that over time they have been able to close that gap,” Lelik said.

For low-income students, tuition can sometimes be more than half of the average pre-tax family income, according to The Atlantic magazine. This sort of financial burden can put a strain on families.

“A lot of times in low-income families, there may be more than one person providing for the family,” Davis said. “When a student wants to go full time, that may be taking a key breadwinner out of the household.”

She also explained the guilt some parents may feel in not being able to financially help.

“There are students where these families want them to graduate college, like they want to support them, but they just can’t financially — that whole thing of guilt and not being able to be there financially,” Davis said.

Student loan debt

More than 40 million Americans owe a combined total of $1.2 trillion in student loan debt, exceeding the national credit card debt. At NC State, the average graduate in 2015 borrowed $17,461 and nearly 55 percent of graduates took out a loan, according to Brown.

In order to help pay off loans, graduates are now working part-time jobs on top of their full-time jobs, if they can find one after graduation.

“Students who came to college expected to come out and get a really good job and then six months after they graduate, they’re like, ‘I’m going to need my money back,’” Davis said. “They’re living paycheck to paycheck, and they’re not able to do all of the things they thought they were going to be able to do in terms of having extra money for vacations, living, traveling — living that good life that they were promised. A lot of them end up getting part-time jobs to lessen the burden and create some extra money.”

Park said he is very stressed about paying off his student loans.

“It’s like an annoying weight I can’t get off my shoulders,” he said.

However, there are bigger societal issues from the impact of student loan debt on the economy, Davis said. Graduates are putting off getting married, having children and obtaining graduate degrees. Debt affects credit scores, which can impact peoples’ abilities to finance large purchases, such as cars and homes.

Consequences and solutions

The increasing costs of tuition and student loans begs the question of whether or not a college degree is worth it. However, Davis said she firmly believes a college degree is still valuable.

“I think if you look at the value of a college degree in terms of earnings, development, positive life outcomes, wellness and mental health stability, it’s still higher for folks that go to college versus those that don’t,” she said.

Another consequence of rising tuition and student loan debt is students choosing their majors based off of money instead of their interests.

“People are like, ‘If I take out loans of $15,000 a year, I need to know I’m going to be able to make that back,” Davis said. “If you’re thinking about starting out and you’ve amassed $50,000–$75,000 of student loans once you’ve graduated, and your salary is only $45,000 before taxes or even lower, how do you even imagine to start paying them back?”

Both Davis and Brown said they don’t see tuition prices coming back down anytime soon. As a cheap solution, Davis suggests that informing students about financing college prior to coming.

“I think we need to talk about and have real conversations about financial literacy, around financial aid, around education debt, costs,” Davis said. “It starts with families, parents, students, but it won’t start when they’re a senior. That’s why it’s important that college counselors exist in high schools. Someone has to do it and we have to start earlier so we can plan accordingly because costs can be quite the shock.”