Researchers from NC State and Pitzer College in southern California recently discovered that many Disney films have a major problem — the number of female speaking roles and percentage of words spoken by female characters has been on a decline.

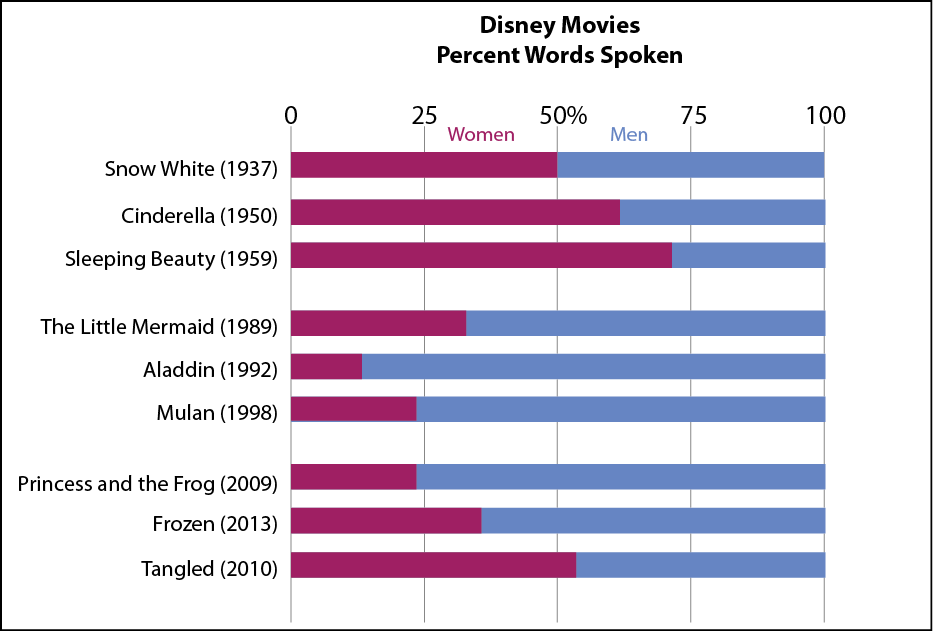

In Disney princess movies released in 1937 and the 1950s, where women’s roles weren’t necessarily empowering, the amount of words spoken by men and women were about equal. However, starting in the late 1980s, that changed with the release of “The Little Mermaid,” where the percentage of words spoken by women went down to 32 percent.

Although “The Little Mermaid” is a movie about a princess who literally loses her voice, that trend continued with women having only about 25 percent of words spoken until 2010, when “Tangled” was released and the percentage of words spoken was about even again.

In movies following “The Little Mermaid,” women spoke only 29 percent of the time; in “Beauty and the Beast,” 10 percent of the time; in “Aladdin,” 24 percent of the time; in “Pocahontas,” 23 percent of the time; in “Mulan” (including when Mulan was impersonating a man) women spoke 24 percent of the time.

However, when it came to speaking roles assigned to cast members, researchers found that it tended to be heavily skewed toward men.

Starting with “The Little Mermaid,” the number of speaking roles assigned to men rapidly outgrew women’s. Even in “Tangled,” in which men and women had about an equal representation in words spoken, less than a quarter of speaking roles were actually women’s. In “Frozen,” the most recent Disney princess movie released, only about a third of speaking roles were women’s.

Karen Eisenhauer, a graduate student studying linguistics at NC State and one of the researchers on the project, hypothesized that growing casts played a part in speaking roles favoring men.

“The animated cast of the films grows by a lot in the 1990s, whereas the originals had 15 characters, the newer films have 40 or 50 roles,” Eisenhauer said. “The guards and shopkeepers, most of those roles, if not all, are assigned male parts. When you add up all those tiny speaking roles it gives the overwhelming speaking majority to men.”

Eisenhauer was surprised by the findings.

“The information that we saw there was in some ways surprising in that we knew Disney films weren’t doing as good of a job at fairly representing women, but we didn’t expect the discrepancy to be as large as it was in some cases,” Eisenhauer said.

Eisenhauer worked with Carmen Fought, a professor of linguistics from Pitzer College on the project.

“This was originally her project that I signed on and expanded,” Eisenhauer said. “Her motivation, which is also mine, is that there is a lot of discourse, academic and nonacademic, about the Disney princess movies and other Disney films about how sexist they are at representing gender to young children. There wasn’t really a quantitative voice being added to the discussion, so we wanted to employ some of the sociolinguistic methods that are used in our fields to back conversations people were having about these Disney movies.”

Eisenhauer said that she has since expanded to topics related to advertising, different movies, and also conducting research as to how Disney operates in order to contextualize films on the company and on the reception side as well as the cultural environment that the movies are released into.

“I would like people to know that this is barely the start of what we are looking at and that we were looking forward to publishing more results as we find them,” Eisenhauer said. “I hope these topics and findings can open more conversation about linguistic representation because we talk about how people look, but there are few conversations about how people sound. How people sound, how much they talk, it’s just as vital as how people look in their representation in the media.”

Students expressed surprise about the findings of the study.

“I find that extremely shocking,” said Amanda Mosely, a senior studying supply chain and marketing. “When I looked at Disney movies when I was a little girl, I always thought that females were the main roles in the films. As a little girl it felt empowering that I wanted to grow up to be a princess. It’s shocking to see movies like ‘Frozen’ and ‘The Little Mermaid’ that women have fewer speaking roles than men.”