When Neal Hutcheson found himself contributing to his roommate’s film projects, he realized film was the outlet he was searching for. Shortly after, Hutcheson transferred from Appalachian State to NC State, which had recently established a film program. Studying film as a creative discipline, Hutcheson grew fond of documentaries.

After graduation, the 1992 alumnus worked as a freelancer for English linguistics professor Walt Wolfram.

“I was interested in culture, and once I recognized that language is a projection of people’s cultural identity, it became pretty fascinating,” Hutcheson said.

Studying the dialects around the North Carolina coast and Appalachia, he developed an interest in Southern culture and folklore. Growing up, he frequented the mountains for camping and hiking trips.

“In hindsight, I’d pass these little towns and wonder about the people living there,” Hutcheson said. “I only had a vague curiosity then; I had no clue I’d one day learn about mountain culture.”

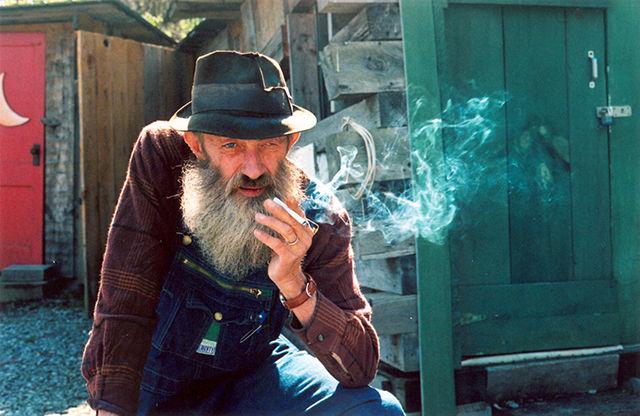

According to Hutcheson, mountain residents are notorious for presenting themselves in a particular way. This held true for Maggie Valley-native and possibly Hutcheson’s most complex and interesting subject to date — Marvin “Popcorn” Sutton, an expert moonshiner and star of three of Hutcheson’s documentaries — “Mountain Talk,” “A Hell of a Life” and “The Last One.”

“People projected onto him that he was a simple guy who wanted to play banjo by the creek and make a little moonshine,” Hutcheson said. “That wasn’t the case; he was brilliant and calculating. That’s why I used the footage I recorded to make that second film, ‘The Last One.’”

“The Last One” complicates the distinction between authenticity and performance, according to Hutcheson.

“If you’re performing your own culture and accentuating it, is that authentic, or fake?” Hutcheson said.

In 2002, Hutcheson made Popcorn a version of the footage to sell along with his self-written book. However, the television-appropriate version wasn’t available until 2008. After its debut, “The Last One” received an Emmy and inspired the Discovery Channel show “Moonshiners.”

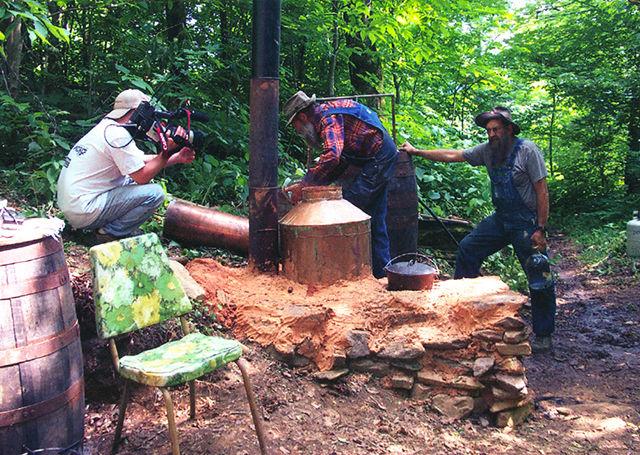

The pretense of the film was to safely capture his “last run” of moonshine. Initially, it wasn’t for the purpose of sharing; in fact, Popcorn only let Hutcheson film on the condition that it wouldn’t be shown before his death. Yet, after viewing the footage, Popcorn liked what he saw.

“I think it was at that point it cemented our friendship,” Hutcheson said. “It was only after he watched it that he allowed me to see his place in Tennessee and film his actual moonshine operation.”

On a coastal filming trip they took together, Popcorn requested to stop at every thrift shop along the way, spending the roll of money in his overalls. He was known to self-promote, charming strangers into buying his merchandise.

“Popcorn had complete faith in the universe to carry him through,” Hutcheson said.

Even though the dialect is so different, Hutcheson found that the isolated fishermen and people living in remote mountain communities had similar personalities. However, after removing Popcorn out of his environment, he grew extremely uncomfortable.

“We planned on staying three days and only stayed for 30 minutes,” Hutcheson said. “The color drained out of his face, and he stopped talking; it was a culture shock. Popcorn had lived in the mountains his entire life.”

By 2009, the law had caught up to Popcorn. With a prison sentence and looming health complications ahead, Popcorn committed suicide. Lighting a cigarette on his way out, he died of carbon monoxide poisoning in his beloved car, the “Three-Jar-Ford,” named for being traded for three jars of liquor. Popcorn took pride in rescuing items that were on the verge of being tossed in the landfill.

Prior to his death, Popcorn signed off his likeness, name and recipe to a Tennessee whiskey label, likely to take care of his wife posthumously. Retrospectively, it was an indicator that his life was coming to a close, according to Hutcheson.

“Popcorn told people he grew up in Maggie Valley, but he also had a home in Parrottsville, Tennessee, where his moonshine operation was,” Hutcheson said. “He tried to deflect attention away from that by spending time in both areas. He claimed that he had dual-citizenship.”

When filming, subjective decisions are made that aren’t always conscious. According to Hutcheson, the final product is a highly selective portrait of the film subject.

“Popcorn allowed me to go deeper into his world so I could see behind the ‘stage,’” Hutcheson said. “To me, that’s the most interesting documentary experience that I will ever have.”

Hutcheson’s latest project, “First Language: The Race to Save Cherokee,” in collaboration with Danica Cullinan, received an Emmy nomination, which will be decided at the awards ceremony in Nashville Saturday. The film concerns the efforts of the eastern band of Cherokee to preserve the endangered language, which was twice as old as English.

For more on Hutcheson’s films, see talkingnc.com and suckerpunchpictures.com.

Filming at Popcorn’s moonshine still in the Appalachian Mountains of Tennessee. The pretense of the film was to safely capture his “last run” of moonshine. Initially, it wasn’t for the purpose of sharing.