Software designers, computer engineers, programmers, web designers, network system administrators, data analyzers and more jobs make up the ever-growing computer science field. However, the U.S. education system rarely starts teaching the basics of computer science until students are well into high school or even college. To improve this situation, a team of researchers at NC State and the University of Florida has developed the perfect tool to teach middle school level kids the basics of computer science: a video game.

The game is Engage, a narrative puzzle-solver where players must navigate a series of increasingly difficult challenges in order to progress through the story. The game has been in development since January 2012.

“When the grant was first funded, we were really tasked with developing a computer science curriculum that could go into a middle school classroom,” said Megan Frankosky, a research psychologist with the project. “That’s a pretty open-ended task. We had to figure out how to fit this curriculum into a game, something that was fun and engaging for the students.”

The premise of the game is that the player is being sent down to an underwater research station to investigate why the station has stopped communicating its ocean research data. Once there, the player learns that an evil villain named Dr. Murdock has commandeered the station. The player must stop Murdock and restore communication in order to win.

“We based our curriculum off of an AP Computer Science Principles course, thinking about what that looks like at the middle school level,” Frankosky said. “We tried to stay away from teaching just syntaxical information, so it’s more learning to think computationally. That can evolve into abstraction, programming itself, writing algorithms and deconstructing problems into smaller parts in order to figure out the steps to solve a problem.”

Players interact with a computer interface in the game to create programs. They then use these programs to assist them in the game by performing actions like moving a platform across a room or operating a crane.

“It’s a very visual connection between what program they wrote and what is happening in the world,” Frankosky said. “Also, there is some level of agency because you are now riding this platform and looking at how the data visualization plays out. It’s visual feedback to what you have written.”

In one room, students have to convert binary from decimal numbers into letters in order to cross a maze. The maze is made from a grid of letters. Stepping on the correct letters allows the students to pass, while incorrectly choosing the wrong letter causes the character to fall through the floor and start over.

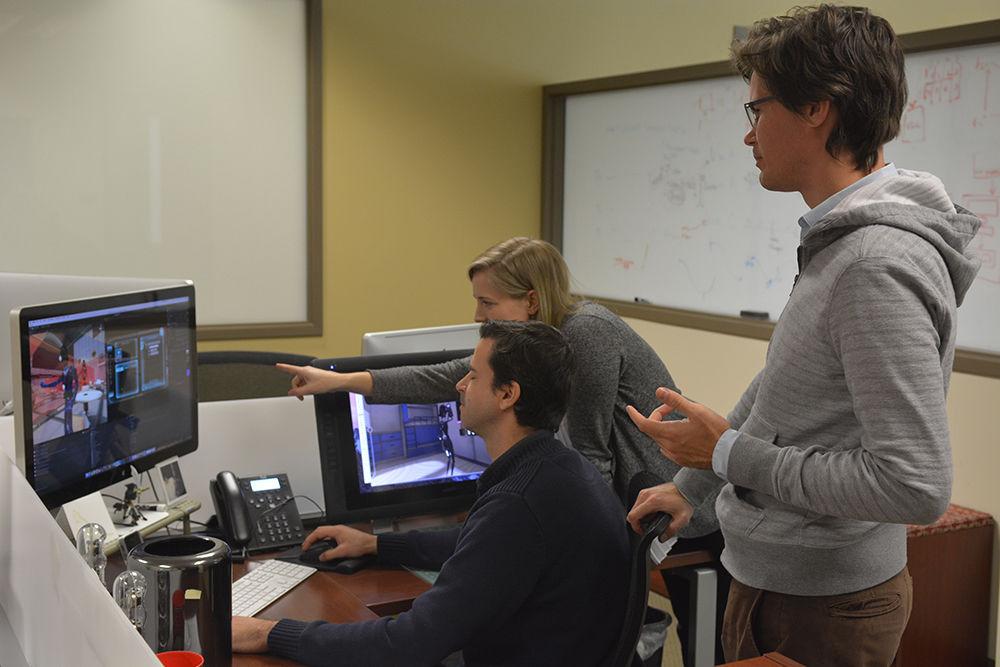

“We met with middle school science teachers so that we could integrate what we want from a curriculum standpoint and work with them to see what is actually possible for what these students already know and are capable of doing at their level,” said Philip Buffum, one of the game’s designers. “It’s appealing because it engages [the students] and it’s appealing to the teachers also because it’s like a built-in curriculum. They can have the students log into the game and go for it rather than having to do so much lesson planning. It acts as a good scaffolding for the teachers.”

Both Frankosky and Buffum have been with the project since the beginning, developing puzzles, workshopping with students and teachers, and refining the curriculum. According to Buffum, the game’s core mechanics are inspired by Portal, a video game where players must solve room-based puzzles to progress through a story.

The game is currently being used as a teaching tool in magnet middle schools around Wake County, including Ligon, Carnage, Zebulon and Reedy Creek.

One student plays the role of a navigator and one student plays the role of the driver. They are distinct roles where one student is manipulating the character and performing the actions while the other is providing guidance on what to do, what to try and where to go next. And then there are points in the game where the players flip roles.

“Collaboration is an overarching computer science principle, but more than just learning how to work together,” Frankosky said. “You are able to bounce ideas off of one another and help bolster each other up. If one is weaker in an area than another, you’re able to work together to solve the problems, which can be more encouraging and effective than if you were to work alone.”

A secondary goal for the program is to bolster diversity in the computer science field by broadening computer science participation in computer science careers earlier in life.

“That [diversity] is an objective of the AP Computer Science Principles that we based our curriculum on, but we want to bring it down to the middle school level,” Buffum said. “One of the reasons we use that curriculum is because it is focused on appealing to students who are traditionally underrepresented in computer science.”

The project recently received a new round of funding from the Natural Science Foundation for three more years of development. Frankosky and Buffum said they hope to get Engage into more middle schools around the state, including non-magnet schools.