Between some researchers and farming advocacy groups, there remains a strong difference of opinion regarding the effects of Genetically Modified Organisms. In addition, many advocacy groups fear the threat of superweeds and they argue the patents on the technology create socioeconomic disparities.

Although the scientific implications of GMOs are still being researched (and debated), Keith Edmisten, professor of crop science, said much of the information the public has about GMOs is either framed out of context, or inherently incorrect.

Currently, there is debate about whether the use of GMOs has created a new kind of superweed resistant to herbicides.

According to a May 2013 edition of Nature, since the late 1990s, U.S. farmers have used GM cotton engineered to tolerate the herbicide glyphosate, which is sold as the Monsanto product Roundup. The herbicide–crop combination was extremely efficient in managing weed growth until it stopped.

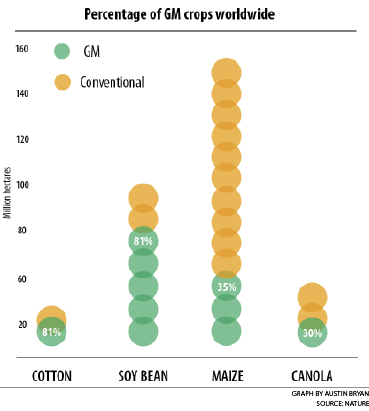

Advocates said GMOs have increased agricultural production by more than $98 billion and saved an estimated 473 kilograms of pesticides from being sprayed, Nature reported.

In 2004, the herbicide resistant weed grass, Palmer amaranth, was found in one county in Georgia, and by 2011, it had spread to 76, Nature reported.

According to Edmisten, contrary to much of public opinion it is not the introduction of GMOs that caused the explosion in weeds but rather the lack of chemistry rotation.

“The resistance was in the Palmer amaranth population,” Edmisten said. “We selected for [the gene] by using Roundup. It has really nothing to do with cotton per se. Roundup was used on multiple crops, often with multiple applications, so we selected for the resistant individuals.”

Edmisten said that opponents who blame massive weed resistance on GMOs fail to understand the chemistry of resistance. He said that if any crop is continually exposed to a single herbicide, as the amaranth was, the crop would become resistant to such herbicides.

Viewpoint from Farming Advocacy Groups

Roland McReynolds, executive director of the Carolina Farm Stewardship Association, an advocacy group for small and organic farms, said large biotechnology companies such as Monsanto have made the playing field that of a “get big or get out” atmosphere for smaller-scale farmers.

“Great talk has been made about the importance of GMO technology to treat seeds that are more resistant and helping populations get the food they need,” McReynolds said. “The reality has been commercialization of GMO technology, which has been resistant to herbicides and pesticides, adds the effect of increasing sales of those herbicides which enforces a policy that hurts smaller farmers.”

McReynolds said the dominance of large biotechnology companies such as Monsanto, which own patents on the GM seeds, makes it difficult for the small farmer who must pay royalties on that seed to use the technology.

“That concentration reduces farmer choice, increases farmer cost and reinforces a 50-year trend that tells farmers to get big or get out. We don’t think this has served rural America or farmers well,” McReynolds said.

McReynolds also said that because of this growing tendency, the state of North Carolina has followed national trends in the loss of agricultural farmland for use by small farmers.

Patents for Seeds

In May, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that Vernon Bowman, an Indiana farmer, infringed on Monsanto’s patent when he planted soybeans that had been genetically modified by Monsanto without buying them from the agribusiness giant.

The decision, written by Justice Elena Kagan, stated that the nine justices ruled that “patent exhaustion does not permit a farmer to reproduce patented seeds through planting and harvesting without the patent holder’s permission.”

Edmisten said that this decision was made due to the precedent set by the Supreme Court in 1980 in the case Diamond v. Chakrabarty.

In that case, the Supreme Court laid the legal foundation that would establish the United States as the global biotech patent leader. In a five to four decision, the Court articulated that the threshold question for patentability of an organism was not whether it was inanimate, but whether it was a product of nature or of human invention. The Patent Office has stated that it “consider[s] nonnaturally occurring, nonhuman multicellular living organisms, including animals, to be patentable subject matter.”

“It is my opinion that it is no different to violate this patent than it is to violate a patent on computer software or medicine,” Edmisten said.

Edmisten said one thing the public is aware of is the fact that when one farmer is not paying royalties for the seeds he uses for his crop, he is taking away from all growers who do pay large biotech firms to be able to utilize their products.

“One thing that I don’t think the public realizes is that the majority of the growers don’t appreciate farmers who try to circumvent the system and plant crops in violation of patents,” Edmisten said. “They resent it when growers try to use a technology for free that they are paying for.”

McReynolds said that biotechnology still has the ability to make many beneficial contributions to agriculture outside of transgenic modification.

“The ownership of that technology by a particular company limits choice and opportunity in the marketplace for innovation,” McReynolds said. “Until the early 1980s, you couldn’t put a patent on the seed, and that provided a lot more variety and a lot more development in the area of classical breeding of seeds and crop varieties. That system was a beneficial one to farmers. “

McReynolds said the more interesting case to consider will be the Supreme Court ruling on the Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics case. In June, the Supreme Court ruled that companies cannot patent naturally occurring human DNA.

McReynolds said that if all naturally occurring genes are held to this standard, the agricultural biotechnology business model will have to evolve.

N.C. State has had a long research relationship with Monsanto, which awarded the University a $500,000 research grant in 2011.