Flyers posted around Wood Hall urge students to help keep the Rocky Branch Creek clean by being cautious about what materials they flush down the toilet.

After reading the flyer, Zack Ellerby, a sophomore in aerospace engineering, said there was something about the thought of students’ waste ending up in a creek that distressed him.

“Yeah, I worried about it,” Ellerby said. “I even lost sleep thinking about it.”

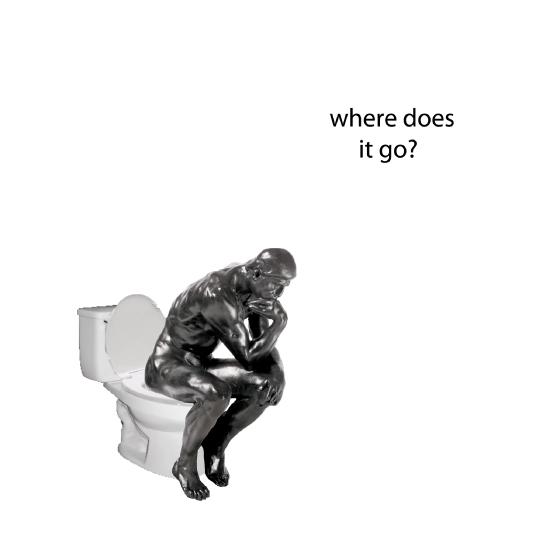

The flyers, though straightforward in meaning and instruction, prompted Ellerby and other students to ask: “After I flush, what happens to my poop?”

Considering that you have no control over the fate of your discarded biological waste or insight into the impact your stool may have on the environment, you might reasonably develop a sort of post-flush anxiety.

“I wonder what happens to it, but I don’t worry about it. I trust that it is going to the right place,” junior in psychology Campbell Dean said concerning the fate of his feces.

The right place Dean mentioned is the Neuse River Wastewater Treatment Plant located in Raleigh at 8500 Battlebridge Road, to which N.C. State sewage finds its penultimate home.

Tim Woody, division director of Wastewater and Reuse, said the Neuse River Wastewater Treatment Plant services about 45 million gallons of water a day. Though the permitted capacity for the plant is currently limited at 60 million gallons, the City of Raleigh expects to expand its permit to 75 million in the near future, Woody said.

Under normal circumstances on campus, solid and liquid waste are flushed through N.C. State sewer pipes and emptied into a sewer system that carries the wastewater all the way to the treatment plant.

At the plant wastewater undergoes a three-step treatment process. This process, combined with a biological nutrient removal process, allows for purified sewage to be separated into two reusable categories; biosolids and recycled water.

“Biosolids are a valuable resource to add nutrients back into soil and adjust the pH of agricultural lands, and more than 95 percent of the biosolids we produce are sent east of Raleigh to be used on agricultural lands,” Woody said.

Recycled water, or reuse water as it is often called, is an efficient means of limiting the drinking water we use for industrial purposes. Recycled water, which is non-potable, is used for irrigation in parks, golf courses and cemeteries city-wide. This water is even used to keep the grass green on the Lonnie Poole Golf Course, which is located on N.C. State’s Centennial Campus.

Any person interested in reclaiming recycled wastewater can contact the Raleigh Public Utilities Department and make an appointment to pick up the reuse water in bulk.

But only under proper disposal protocol does your waste end up the benefactor of fairways, greens and cemetery plots. There are limits to the things you can flush. While grease and oil are the most common causes of constipated sewer systems, food scraps, paper towels and tampons can be just as destructive to the natural flow of sewage through the city’s bowels.

Students can avoid any awkward reencounters with their biological byproducts at the Rocky Branch Creek or elsewhere by adhering to this general rule: If it didn’t come out of you and you didn’t wipe with it, don’t flush it.