Though the computer science and English departments may not be known for their collaborative efforts, one professor has been working to break down the barrier between the “hard sciences” and the humanities.

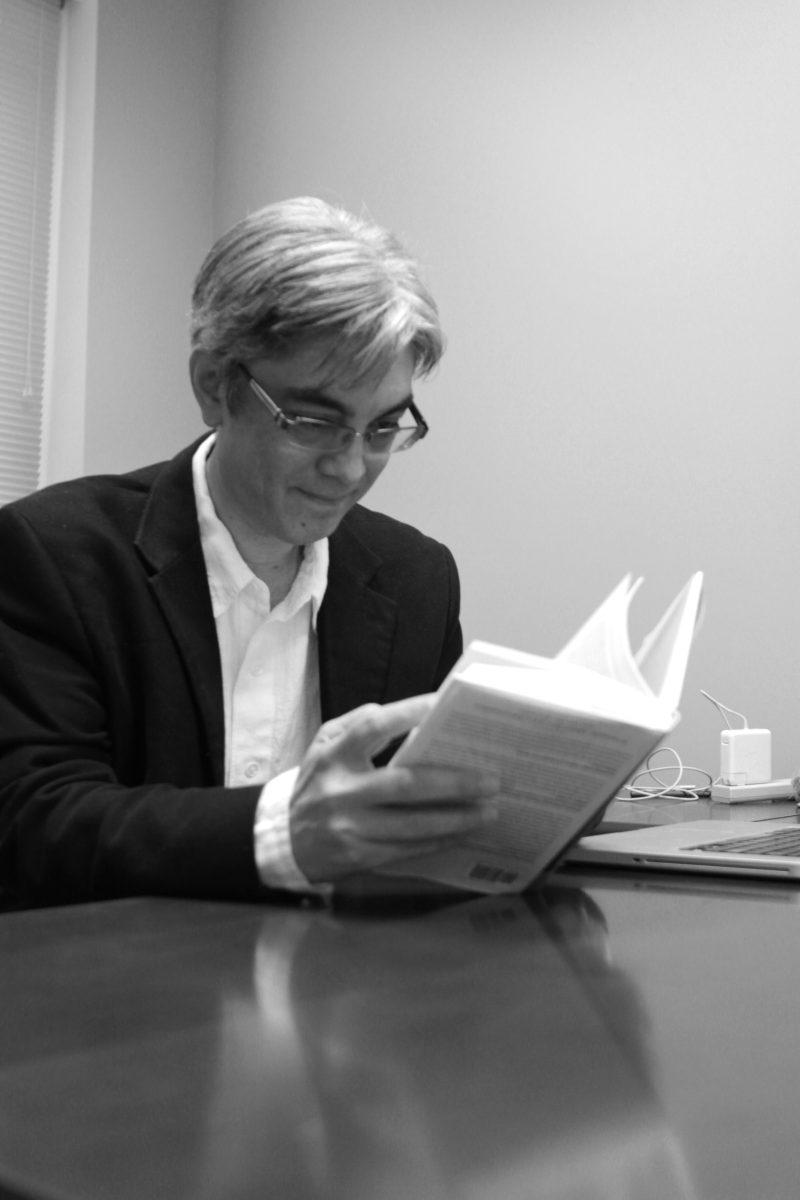

In October 2012, Robert St. Amant, professor of computer science, released his first book, Computing for Ordinary Mortals, which illustrates from areas of computer science and ultimately provides a look into what drives the field of computing forward.

Though he had always wanted to write, St. Amant never saw it as a true probability.

“I’ve always thought, ‘I’d like to write a book some day,’” St. Amant said. “So it’s always been in the back of my mind.”

However, writing an instructional book on computation was not his initial goal. While taking a graduate writing workshop at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, St. Amant opened himself up to the world of writing.

“I originally wanted to write fiction, but in the end I decided to write about what I know there’s less of that than what I don’t know,” St. Amant said.

Computing for Ordinary Mortals began as a side project, but St. Amant soon found his work could be much more useful than he had expected.

“As I wrote the book, I gradually realized that what I was writing about computing is really important,” St. Amant said. “There are lots of books out there about how to use computers and program computers, and they give you just enough conceptual background so that what you’re doing makes sense.”

What sets his book apart, he said, is the fact that it details the human interaction with the machines that society has embraced so ardently.

“The goal of my book is to bring those concepts into the foreground, because to me they’re the most interesting part,” St. Amant said. “They give you a way to think about computing. They help you understand why computers work the way they do, what’s possible and what’s impossible to do with them.”

To do this, St. Amant sends his readers on a journey living vicariously through situations in which different characters must solve problems with the help of computers and computer programming. Some situations, he said, have come from real experiences within the classroom.

Because these situations can be so familiar, St. Amant plans to use examples from Computing for Ordinary Mortals in his classes as an alternative to the typical textbook.

While computer science doesn’t appeal to everyone, St. Amant said his target audience is largely those who want to learn more about the field but may be intimidated by the “unforgiving nature of the modern computer.”

“A lot of people are still intimidated by computers,” St. Amant said. “When you do the slightest thing a computer system doesn’t expect, it describes what’s happened with phrases like ‘fatal error’ and ‘illegal instruction’ and ‘kernel panic.’ It might ask whether you want to ‘abort,’ ‘terminate’ or ‘kill’ a process. All this jargon makes computers seem less forgiving than they really should be. I wanted to bring across ideas about computing in a way that wasn’t so demanding and critical.”

In the future, St. Amant hopes to expand upon his writing portfolio with a genre not totally removed from the technological.

“I spent a few days last summer plotting out a science fiction/fantasy book for teenagers the kind of book I liked to read when I was growing up that involved computer concepts, but I have no idea whether it would be readable or even whether I’d be able to write it,” St. Amant said.

According to St. Amant, readers do not have to be in a computer science related field to enjoy Computing for Ordinary Mortals, though he imagines his main audience is one that already likes to read popular science pieces about how the world works.

“I think you can get some good intuitions about computing with a few hours of casual reading,” St. Amant said. “You won’t have the same background that someone with a degree in computer science has, but that’s ok no one reads A Brief History of Time [by Stephen Hawking], for example, and expects to come away being a professional physicist.”

No matter what literary genres find their way onto your bookshelves, St. Amant hopes the general public will take a step out of their comfort zone to look at the interactions between mankind and arguably one of the most influential inventions in history.

“Computing happens in a world of information and information processing, and learning about computing is something like finding out that at the microscopic level biology looks very different from our everyday experience,” St. Amant said. “Computing is something like that familiar on the surface but interestingly different underneath.”