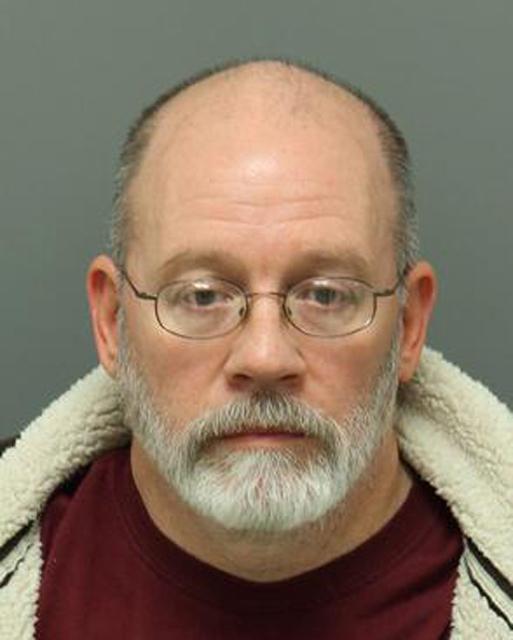

Tardigrades are one of the only animals on Earth that can die and come back to life, and Harold Heatwole, a professor of biology and tardigrade expert, has collected thousands of them.

Tardigrades, also called ‘water bears’ and ‘moss piglets,’ are microscopic creatures. Only the largest tardigrades can be seen by the naked eye. They do look a bit like minuscule bears with eight stubby little legs—three on each side and two on the back. Their skin is translucent and one can see the all of their organelles and everything they’ve eaten inside of them as they waddle around.

The thing that makes tardigrades so exceptional is their ability to go into dormancy whenever conditions are too extreme—for example, if there is too little water or too much salt. This is called cryptobiosis, which means “hidden life.”

“They lose almost all of their body water. That of course is something that most animals can’t do. I mean, if we lose about 12 percent of our water weight it’s lethal,” Heatwole said.

What baffles scientists is that when tardigrades go into their dormant state, they completely shut down their metabolism.

“By any biological definition or any legal definition, they are dead,” Heatwole said, laughing. “But they don’t know it.”

They can last for years in this condition, shriveled up into a state scientists call tuns, and all it takes to revive them is a little bit of warm water.

“If you could understand how they go in and out of that, you’re really getting at the essence of life,” Heatwole said.

Scientists do understand the drying process – to preserve themselves, tardigrades substitute their body’s water for glycerol and also modify their sugars. Still, they do not yet understand how tardigrades can come back to life or why water begins the process.

While they are in tuns, tardigrades are resistant to adverse conditions that would kill any other known life form. They can survive temperatures down to nearly absolute zero up and to 300 degrees Fahrenheit. They can be irradiated, fumigated and even exposed to toxic chemicals, and they’ll be fine.

The European Space Agency even sent some of them into space during a mission called Tardigrades in Space (TARDIS for short), which left them in the vacuum of space for 10 days. They were perfectly healthy when they were recollected and rehydrated, and they even went on to reproduce normally.

There are two main types of tardigrades. One group lives on the film of water on the surface of moss and lichens, while the other lives in the wet sands of beaches. These marine sediment tardigrades are very hard to find and study, so not much is known about them. Heatwole studies the tardigrades that live in mosses—nearly a thousand species have been discovered.

Over the past few years, Heatwole and one of his Ph.D. students, W.R. Miller, have been studying tardigrade distribution.

Tardigrades may be most abundant in extreme conditions, but they live all over the world. Heatwole and Miller have been working together to collect tardigrades on an international scale. So far, Heatwole has collected tardigrades from places such as Antarctica, Serbia, Tristan de Cunha, China and several locations in Africa.

Tardigrades are one of the larger microorganisms—and virtually indestructible—so they aren’t too hard to find. Miller has written a pamphlet describing tardigrades and how to research them so they can be studied in high school classes. It has been translated into many different languages, including Russian and Japanese, and students who use it often send back specimens that they discover to the researchers.

“One of these students found an undescribed species in his backyard,” Heatwole said. “These high school students are sending in moss and tardigrades from all over the world.

With all the tardigrades pouring in, Heatwole and team are currently working on research papers.

“The nice thing about tardigrades is when you collect them, all you have to do is put the moss in a paper bag… and if you’re busy just put it on the shelf and a couple years later you can pull it down and pour some water on it and they’re still there,” Heatwole said. He and his team do have preservation methods, but they have collected many tardigrades that are yet to be studied.

“Like any animal, we want to know as much as we can about them, understand the life around us and its diversity and preserve it,” Heatwole said. He paused and then laughed. “Well, these things, of course, are fairly easy to preserve.”