Sadlack’s Heroes, Schoolkids Records, The Groom Room Barbershop and other businesses currently inhabit the block between Enterprise Street and Maiden Lane. However, in just more than a month, by Dec. 31, they will have to pack up and leave. Their replacement? A 125-room luxury hotel.

N.C. State, the owner of that plot, awarded a contract to build a hotel and ground-floor retail and restaurant center to Bell View Partners of Raleigh and The Bernstein Companies of Washington, D.C. (Of the businesses located in that complex, the Bell Tower Mart and Soo Cafe plan on returning to that ground floor.) In 2011, the owners of the businesses that would be displaced found out about the finalized deal not through the University, but through affected customers and media phone calls; i.e., only after the news went public.

Sadlack’s Heroes has been on Hillsborough Street since 1973. Sadlack’s is a sandwich shop (with notable vegetarian options) and bar and music venue (the only one on Hillsborough Street). It’s also dog-friendly. But most importantly, it’s a community hub. Not too much of a student community (like Mitch’s), but community nevertheless: From the down-and-outers that refined college students are supposed to feel ill-at-ease associating with, to Zach Galifianakis, who said he tries to stop by there whenever he’s visiting town, Sadlack’s is where real culture — expression and experience by the broad community of outside institutionalization and commercialization — still resides.

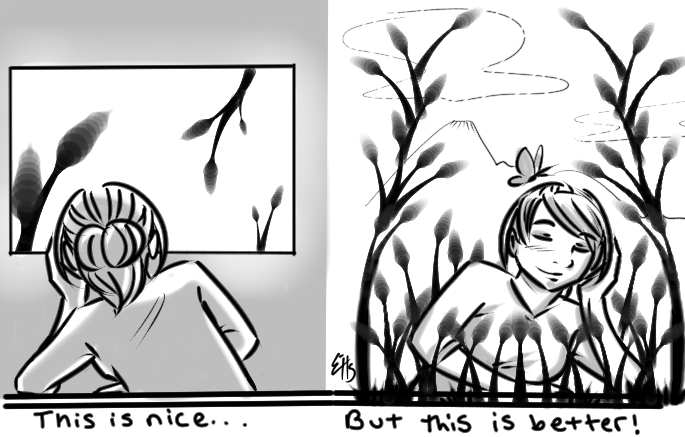

Places such as Sadlack’s are the ones that connect us to our culture; they have an atmosphere exuding a gritty-yet-warm genuineness reminding us there’s more to the world than what’s reflected off our glossy college degrees. But they are being done away with.

There’s a word for this: gentrification. This is the process by which an area is renovated and improved so as to conform to middle-class taste. It’s been happening on Hillsborough for quite some time now, and sadly, much of the sentiment for this on campus has been positive.

It hasn’t always been happening, though. In his story “Keep Hillsborough Street funky,” Bob Geary, writing for IndyWeek in 2009, traced the street’s history as being the epicenter of Raleigh’s identity and culture — “the place where Raleigh’s disparate parts are joined in an authentic urban whole” — and recalled its heyday. But by the 1980s, he lamented, “Raleigh had moved on,” Hillsborough Street declined and “[s]oon N.C. State turned away, shutting the street entrance into its main library, D.H. Hill, and hiding other buildings, including the chancellor’s residence, behind tall shrubs.”

And N.C. State, as it is today, became fragmented from the urban whole, and as education became more and more a thing of privilege, it rejected — through its administrative initiatives and students’ own recreational choices — culture that was more than a mere commodity for students’ restrictedly socialized tastes. As N.C. State became more disconnected, that created more disjunctions in the culture and community around the area, it led to more purely commercial setups on Hillsborough Street. And today, to me, Sadlack’s and the Reader’s Corner down west are the last vestiges of authentic, vibrant culture in the N.C. State-Hillsborough Street area. (Apart from Cup A Joe and Global Village perhaps, but coffee shops are meant to be community spots by definition. Mitch’s is another contender, but its mainly exclusive N.C. State atmosphere, and its contemporary university detachment curbs the kind of messy equilibrium with its surroundings to qualify it as a producer of real culture.)

But gentrification isn’t bad just because of the value of authentic culture — connected to its place and native residents and free to unfold outside of the directedness of capital. It deals tangible consequences upon many. As property values in and around a newly renovated hub increase, lower-income people are displaced, and soon, the city is neatly divided into haves and have-nots. This isn’t completely the case yet for the area behind Hillsborough Street, which is still remarkably diverse, but if luxury hotels and redevelopment initiatives have their effect, it will be.

Raleigh has already been tremendously affected by gentrification though. As Ryan Thomson wrote about downtown in his column in September in lieu of the incident of police threatening to arrest community group members for feeding homeless people at Moore Square, “The block … situated on S. Pearson and E. Hargett St. (once referred to as “Raleigh’s Main Black Street”), is currently worth around $7.7 million … (but is being appraised much higher). In light of this process, the city’s recent relocation of the Salvation Army begins to paint a picture of gentrification.”

His description of the downtown “redevelopment” efforts can stand for Hillsborough Street as well: “The history books will likely reflect a similar narrative to that of Fayetteville Street having now been “beautifully restored,” but in doing so we neglect the communities and cultural nuances of the Oak City … The redevelopment narrative and would ultimately seek to create yet another Brier Creek or Glenwood South by expanding the commercial district.”

In the nick of time, this September, Sadlack’s announced that it had found a place downtown on Martin Street to relocate. Schoolkids Records is moving to Mission Valley. But Hillsborough Street won’t be what it used to be. Katmandu and Shakedown Street won’t ever be back. Sadlack’s will be somewhere else, and won’t be the same thing. We’ll celebrate the polished floors and characterlessness of Saxby’s Coffee and a Starbucks in the new Talley, we’ll drive-by, smirk at Cup A Joe’s griminess, and we’ll continue to exercise our finely honed, upwardly mobile sense of good and bad. We’ll cease to experience the world in a rich way, and worse, we’ll annihilate its richness. Some of us might even live our white-picket-fence fantasies, but on the other side of the fence, there won’t be a sandwich place left to go to when the cash flow has fizzled out to redevelop our side.