Will you choose to settle down in the big city, the calm country or somewhere in between? Your preference is based on a variety of different factors, but do you ever consider the sounds of these places? Oysters do.

Ashlee Lillis, a post-doctoral research fellow, researched how sound affects where oysters choose to live — even though they don’t have ears, as she stated in a N.C. State news release written by Tracy Peake.

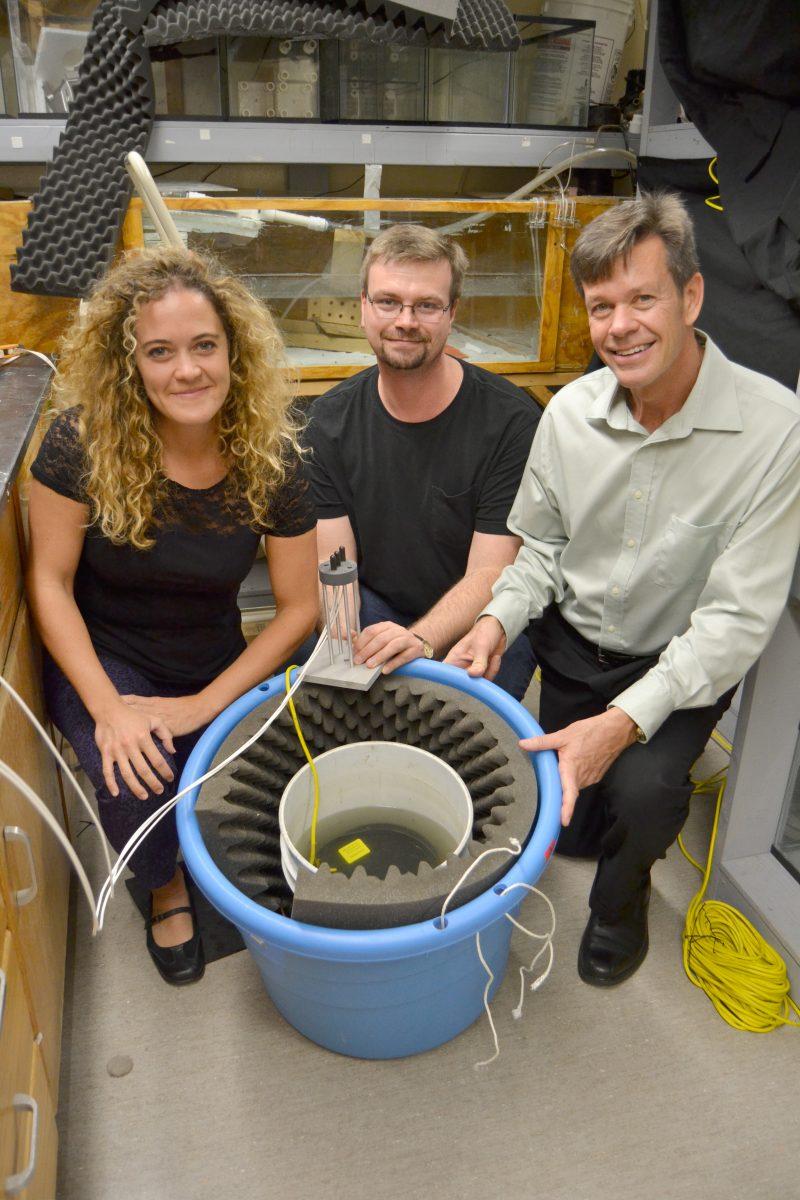

Lillis does this research with her professor, David Eggleston, and in collaboration with geophysicist Del Bohnenstiehl, beginning in summer of 2010 and ending in summer of 2012.

“The ocean has different soundscapes, just like on land,” Lillis said in the release, “Living in a reef is like living in a busy urban area: There are a lot of residents, a lot of activity and a lot of noise. By comparison, the seafloor is more like living in the quiet countryside.”

Lillis studied larval settlement cues for her undergraduate thesis and as a master’s student. She said that soundscapes “seemed like an avenue of research that is not only fascinating but relatively unexplored.”

To test the effects of ocean soundscapes, Lillis and her professors put oysters from hatcheries from the University of Maryland and a hatchery in North Carolina into cylindrical tanks, capable of holding 20 liters, with speakers at the bottom playing sounds that would be heard in different locations in the ocean. They then measured how many oysters chose to settle.

At first they waterproofed computer speakers, but then gained funding to purchase underwater speakers, which Lillis said “can better reproduce the sounds.”

N.C. State’s The Abstract put some of the recordings they used, both from reefs and soft-bottom habitats, online. The reef creates more noise; almost a crackle. Students can listen to them at http://web.ncsu.edu/abstract/science/snap-crackle-pop/.

According to Lillis, there are more sounds coming from the reef due to a “higher density of sound-producing organisms (i.e. fish, shrimp).”

The researchers recorded the amount of settlement, which Lillis defines as the “attachment to hard substrate,” when they played each of the sounds. The result was that more oysters chose to settle when the sounds of the reef were played.

However, sound is not the only factor in oyster settlement. Surface characteristics, physical cues and chemical cues are all factors in choosing where to live.

“Sound is one of many signals that may be used, and is potentially used over broader scales than some of the others because it can travel farther than other cues and may be more consistent,” Lillis said.

According to Lillis, the research is far from over. They will test other behaviors based on sound, such as sinking and swimming. Lillis said they also plan to play the recorded sounds in the natural environments in order to test if the initial results “have an ecologically significant effect on natural settlement rates.”

All in marine, earth and atmospheric sciences, Ashlee Lillis, a doctoral candidate, DelWayne Bohnenstiehl, an associate professor and Dr. Dave Eggleston, a professor research whether habitat-related sounds cause the settlement of marine larvae. Lillis said, "being on the leading edge of a new field is really fun, interesting and exciting," as she explained that the bucket serves as an experimental tank to replay underwater sounds to oyster larvae cultures.