You are nothing.

Wellesley High School teacher David McCullough’s now-infamous graduation speech was titled “You are not special” for good reason.

Will McAvoy’s famous monologue from The Newsroom paraphrased this sentiment thus: “ … you, nonetheless, are without a doubt a member of the WORST period GENERATION period EVER period.”

Goading young people with these sorts of taunts is nothing new. Our parents do it to us just as their parents did it to them, et cetera, et cetera. Some would argue that it’s even necessary. Without these reminders, the thinking goes, young people would develop too haughty a sense of self, too much self-importance, too much of a sense of entitlement.

And therein lies the heart of the problem: entitlements. “Nothing” that is entitled to a free education is still “nothing.” “Nothing” that is entitled to free healthcare is still “nothing.” Entitlements serve only to aggregate a nation of spoiled nothings. The Greek philosopher Parmenides argued correctly that “… something cannot originate from nothing,” and the evidence is plain enough. People who believe they are entitled to something will do exactly nothing to earn it (otherwise, it would be an earning and not an entitlement).

I had a conversation with a young man in my computer class some weeks ago about this very subject. He prefaced our discussion with a disclaimer: “I believe everyone is entitled to a free education and free healthcare,” he said. Sounds good, I suggested, but “free” doesn’t actually mean “free.” Nothing is free. “Free,” I said, is simply a code word for “someone else should pay for this.” Or better yet, “I feel entitled to take that which someone else has earned and keep it for myself.”

I suggested to this young man that he is, in fact, a supporter of guns and slavery. Wild-eyed and with his face twisted in rage, he told me he was nothing of the sort. I reminded him of what slavery is; it is to be wholly deprived of the fruits of one’s labor. It is to be held in this sort of perpetual servitude. Professors and administrators don’t spontaneously organize themselves into universities by divine conception or some innate sense of duty; they do it because they expect compensation for their labors; services rendered for fees paid. And if the young man receiving this education isn’t going to pay for it, then it suggests that someone else will.

This young man, by virtue of his “free” education, would receive the fruits of someone else’s labors for absolutely nothing in exchange.

Worse yet: those “someone else’s” won’t have a choice in the matter. If they choose, for instance, not to surrender part of their income to pay for the entitlements of others, then this young man would eagerly sanction the use of the government to confiscate those moneys, by force, if necessary. And they will, most assuredly, use the most powerful tools of their trade to execute this coercion. Guns, ironically, that were paid for by even more funds coerced from the fruits of those who have labored.

This young man predictably guffawed at my logic and started to lecture me about “the public good” and “democracy,” how “the majority” have chosen these things.

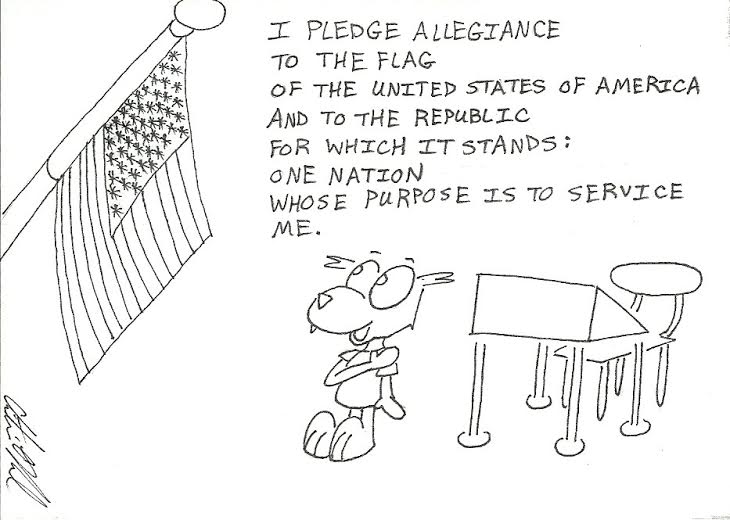

To which I reminded him that never in the history of this country have we pledged allegiance to the flag and “to the democracy for which it stands.” And just because the majority wants something doesn’t make it morally or ethically right.

The conversation sputtered at this point. Bewildered and breathless, he grasped at every last straw he could. And I smiled at him, because now he was working for his point of view, fighting hard to defend himself.

In not yielding to his sense of entitlement, I stirred the very best in him; a willingness to work for his position. I encouraged him to refocus this energy not on me, but on his own life. I told him he needs to have nothing handed to him because he has everything he needs inside of himself to generate the wonderful and prosperous life he is undoubtedly capable of — that by earning his way, he would free himself from the perpetual state of servitude that a culture of entitlements sentences us all to.

He still hasn’t spoken to me since, and that’s fine. I, too, resented the people around me who reminded me that I was nothing. I resented them as I worked hard to prove I was, indeed, something.

And in that, those people who taught me such an important lesson gave me something more valuable than any entitlement I could have possibly imagined for myself. I wish nothing less for that young man.