When learning about passive voice, most English-language, writing classes will get a quick history lesson. That lesson is really just a shout out to the most prominent example of passive voice in American political rhetoric.

The example, “Mistakes were made,” might as well have been Richard Nixon’s catchphrase. But the mantra has been and is still used by many politicians.

In 2007, social psychologists Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson published a book, Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me), which explored how we rationalize our behaviors on personal and social levels.

Most importantly, they explored the importance of how we use rhetoric such as that three-word, political catchphrase to deflect fault and blame from ourselves. Get it?

N.C. State students may recall the controversy surrounding the student body president election last spring, as one of the candidates was revealed to have posted several homophobic, sexist and Islamophobic remarks online. He dealt with the situation by diverting the blame from himself, claiming the remarks were the works of his meddling friends on all of his social media accounts.

We, as a people, have difficulty admitting our faults. We have even more difficulty owning the mistakes that arise due to these faults.

The past two Mondays saw headlines in which someone owned up to his mistakes.

Dan Cathy, CEO of Chick-fil-A, said he regrets having spoken about his personal and religious-based views regarding homosexuality. More specifically, he said he regretted the entire ordeal that followed and led to a significant decline in sales for his fast-food chain.

Cathy said he would be a fool for not learning from his mistakes.

Though his reasoning for recanting his statements seems a bit lucrative, he does seem to have grown from the experience—even if that just means he will no longer donate to conservative, anti-gay organizations.

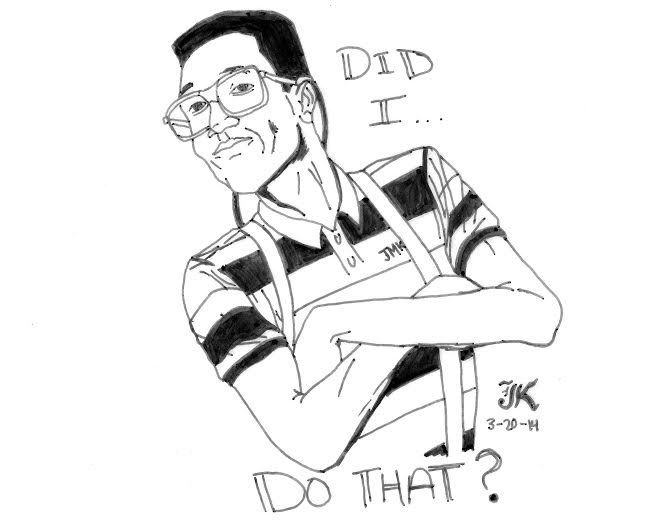

Angus T. Jones, known for his role as Jake Harper on Two and a Half Men, urged his audience to stop watching the show, as it fills our heads with filth. Jones said he was a “paid hypocrite” and does not agree with the messages or jokes the show puts out.

Jones cited his newfound faith in Christianity as the source of his guilt, claiming additionally that he would prefer to act in “Bible-based stories.”

Cathy and Jones both identified the detrimental effects of their actions and decided to make a change.

Though Cathy said he wished he could retract his statement because of the damage to the company’s image, he still understood the implications his words had on the LGBT+ community. He was able to rise above personal beliefs and demonstrate that a company (composed of many workers with vast political affiliations) and its CEO don’t have to support the same values.

Jones had no reason to deter audiences from the show other than his own guilt. He didn’t try to rationalize his involvement with the show, arguably taking more blame than deserved.

These are only two examples, but they exemplify taking responsibility incredibly well. We learn from Cathy that sometimes it’s best to put personal biases aside for the sake of fostering a welcoming environment. From Jones, we learn to take notice of how we contribute to a system of oppressive attitudes and behaviors.

I urge everyone to take notice of Cathy and Jones’ examples. People must understand that owning up to our mistakes yields far more respect and far better results than attempting to deflect blame.

Everyone makes mistakes. They are an integral part of learning, as well as personal and social growth. In the script that is human nature, it is written on every page that we must err. Let’s together evolve this species of ours into one that can, with love, own our mistakes.