N.C. State solar cell research has led to an entirely new theoretical model about how solar cells are manufactured. However, critics caution that real-world benefits are a long way off.

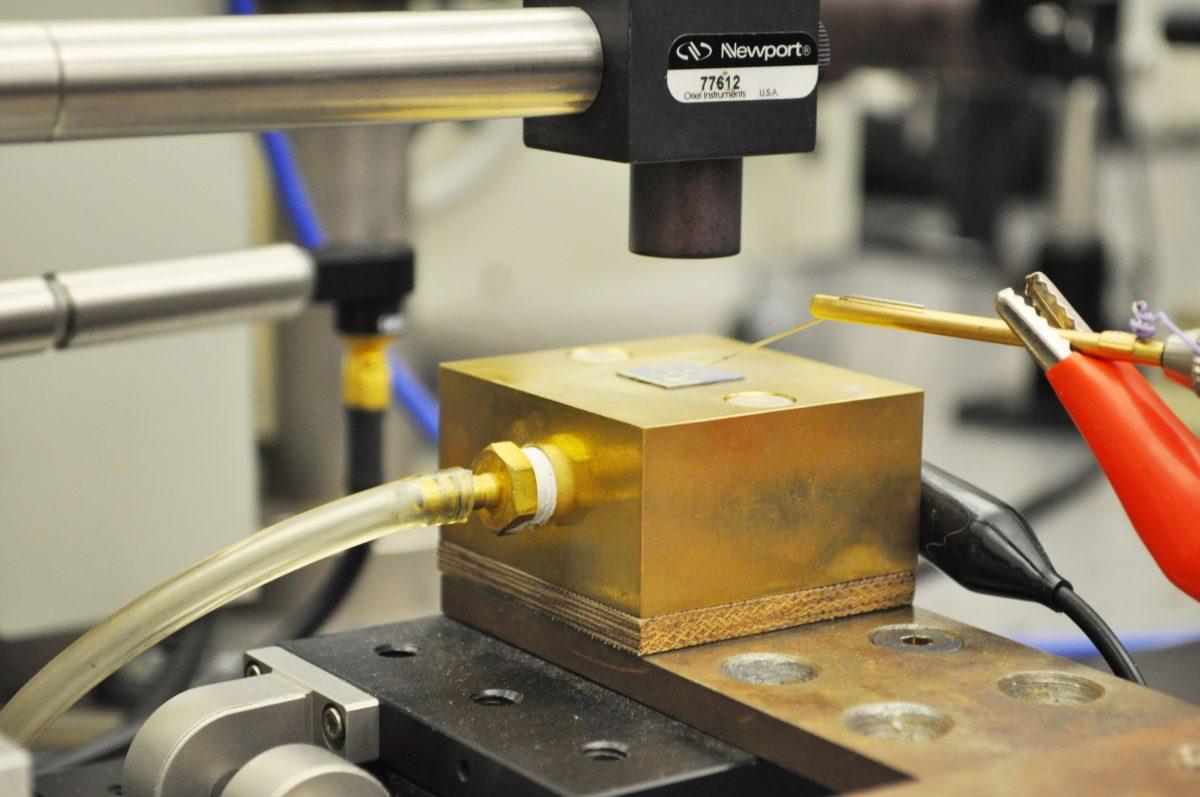

Linyou Cao, assistant professor in the department of materials and science engineering, published a paper last month in Scientific Reports detailing a new solar cell manufacturing model that, if developed, could drastically reduce costs and increase efficiency.

“In solar-cell creation and manufacturing, a key challenge is that the cost is too high,” Cao said. “To decrease cost, we need to optimize the manufacturing process, which makes up the majority of solar cell cost.”

The “super-absorbing” design could decrease the thickness of the semiconductor materials used in thin film solar cells by more than one order of magnitude without compromising the capability of solar light absorption.

“The structure we’re proposing can absorb 90 percent of available solar energy using only a 10 nanometer thick layer of amorphous silicon,” Cao said. “The same is true for other materials. For example, you need a cadmium telluride layer that is one micrometer thick to absorb solar energy, but our design can achieve the same results with a 50 nanometer thick layer of cadmium telluride. That’s a huge advance.”

Cao said this research is a step forward from current solar-cell manufacturing processes because it’s an entirely new design model. After researching similar solar-cell related issues as a Ph.D. student, Cao said he continued after becoming an N.C. State faculty member.

“When I started at N.C. State, I started thinking about the more basic questions—what is the final upper limit for solar absorption,” Cao said. “It can’t be infinite. The existing theory couldn’t answer that question, so I had to come up with an entirely new theory.”

At this moment, it’s all still theoretical, Cao said. But because of the design, it should be easy to commercialize, as it can fit current thin-film manufacturing facilities. Right now, Cao is looking for an industrial partner to implement the design.

However, thin-film solar cells are not widely manufactured in the U.S., said Tommy Cleveland, a Solar Center engineer.

“A fairly small percentage of solar cells fall into this category, and right now, the majority of solar today is made of crystalline silicon panels, which is not the same thing as thin film,” Cleveland said.

However, Cleveland said the solar community should receive this research as a “theoretical success.”

“They haven’t yet built their idea,” Cleveland said. “It’s designed to minimize costs in the manufacturing process, which is a great thing and important for the continued growth of solar energy. But, it won’t have a direct impact on the panels you can buy and install until it’s manufactured at low cost.”

Also, thin film hasn’t lived up to the promise of providing cheaper solar energy in the past, Dan Lezama, owner of Sun Dollar Energy of Raleigh, told the Triangle Business Journal in February.

“Thin film has been around for a long time, and we have always hoped it would provide cheaper solar, but it has not delivered as of yet,” said Lezama, who did not return the Technician’s requests for comment. “Up until now what has happened is that anything more efficient is more expensive. Anything cheaper is less efficient. Any new technologies will ultimately be measured by the yardstick of the existing silicon-based PV technology, and it will have to compete on a cost-power-watt basis, which up until now thin film has had a hard time doing.”

Cao declined to comment about skepticism about his research.

Cleveland said skeptics have to remember current solar cell technology took decades to produce cheaply. The challenge is now to use Cao’s design in high volume low cost manufacturing, he said.

“Whenever there’s a dramatic change to the manufacturing process, it takes a long time to fine-tune the details,” Cleveland said. “But I still think this research is a great thing that has the potential to have a big impact on solar energy generation around the world.”