We Americans are lovers of the underdog story. The very conception of our nation is a classic example of our quest to prove wrong the detractors of our visions and dreams for a better existence. Since our revolution, the idea of “pulling oneself up by their bootstraps,”—of achieving the unthinkable through sheer willpower—has permeated our national ethos, galvanizing our greatest accomplishments and defining our most valiant defeats.

The notion that exceptionalism drives success is a compelling one, brought to the attention of our national dialogue as recently as last weekend in The New York Times’ Sunday review.But while the outcomes of many-a-story and victorious conquest leave little doubt to the necessity of unrelenting obstinacy for achieving greatness, the belief that we may all achieve our most treasured fantasies threatens not only our self-esteem, but our ability to redefine greatness as something within the reach of any human being. One need not look further than today’s generation of college students, the millennial generation, to comprehend the implications of an unwavering belief in the possible.

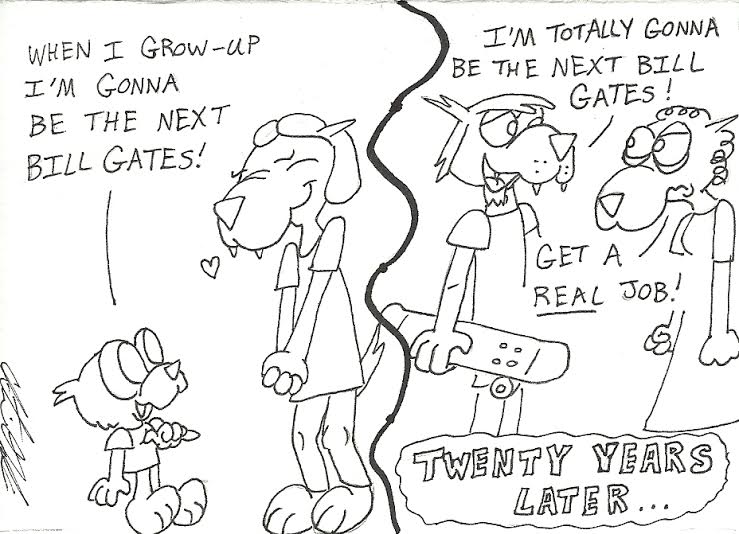

The millennial generation faces the unique difficulty of being caught between the lofty promises of their youth and the unfortunate circumstances of today’s economic reality. Told that they could be “anything they wanted to be” by parents and caretakers from a baby-boomer generation that experienced the empowering economic upturn of the late 1990s, millennials were given the seeds of inspiration to not only follow their dreams—but also to genuinely believe that their dreams would materialize when given enough perseverance and dedication to their pursuits.

The limitations of today’s job market remind us that such possibility is far removed from our American convictions of an unbound self-determination. An undergraduate diploma is no longer enough to secure the beginnings of a promising and stable career for young graduates. The Pew Research Center reports that since 2010, the share of young adults ages 18 to 24 who are currently employed has been its lowest since the government began collecting this data in 1948. Forbes echoes this sentiment, noting that some 36 percent of young adults between 18 and 31 are still living at home with their parents. Numbers like these foretell a dismal job market for undergraduates, dashing remaining hopes of following dreams in lieu of pursuing studies that guarantee more realistic job prospects.

NDN Fellow Mike Hais observed the consequences of students’ vision for the future in a recent USA Today article, acknowledging that “younger people do tend to be more stressed than older people do…they just don’t know where they’re going in life.” Without much economic certainty on the horizon (as if there ever was), collegiate millennials must come to terms with the increasingly unrealizable expectations of their former youth, or face the anxieties of falling short of their many aspirations for greatness.

While I would never be one to tell a friend that they aren’t special, a dose of humility can prove useful in recognizing the limited extent to which one can actually achieve their dreams of becoming president—especially if they lack an interest in political participation. Accepting some limitations as reasonable barriers to envisioned successes can be empowering if done in the correct light. Every road that we choose to forego is one less road to worry about when charting a course for the future, even if it means renouncing certain childhood dreams.

The stereotype of defying all odds to achieve greatness is inspirational, but not relatable to most of our everyday lives. Many of us can achieve our own versions of greatness if we define the concept of success as something other than celebrity or limitless affluence. While college is a sacred time to think big about one’s possibilities in the world, completing today’s small tasks proficiently—like being kind to one another—secures an immediate greatness that is foundational to continued future success.

Send Neel your thoughts at technician-viewpoint@ncsu.edu.