Diagnostics is probably the most non-medicinal subject in medicine.

Diagnostic Handbook, written by Esagil-kin-apli, the most extensive medical text of the last millennium B.C., introduces empirical deductions and logic in the field of medicinal diagnosis. Diagnosis of an ailment is wrought with ambiguities such as incomplete medical history of a patient, dynamic environment that the patient lived in, a many-to-many relationship between symptoms and ailments, etc.

A skilled diagnostician, likely a veteran in the field, is often like a blind man, touching, smelling and watching reactions of his movements on the subject to deduce the true nature of his quarry. Often in that process, the diagnostician employs treatments that are incorrect solutions, which results in undesirable side effects.

Hence, diagnostics holds a unique description: the study of finding problems.

Once you know the problem, the treatments are a simple matter of reading textbooks. If only technologists could learn from diagnosticians.

Information technology, if it has to become a ubiquitous problem-solver, must learn to respect geography. To understand that, one must first understand existence of problems.

A rough categorization will help me prove my point. Most problems arise out of social, economic, physical and geographical environment of the problem-bearer. Problem-bearers are either single or plural. Problems ailing a community or a state are often social, economic or cultural in nature; for example, poverty, illiteracy, and, for that matter, even rape and racism. The physical and geographical ones are often distinct, such as communication, knowledge, locomotion, etc.

The problem of lack of instant information was solved by the advent of the smartphone and the Internet. The smartphone was a solution to a universal problem. Hence, it thrived everywhere. This is a problem that was well-addressed by technology. The solution was born in the United States and spread across the rest of the world. Everyone welcomed it because it solved a fundamental problem, but traffic planning should have been addressed differently.

Here in the U.S., roads are filled with cars, and a two-wheeled vehicle is a rare sight. Hence, lanes are elegant, simple and solve the problem very nicely.

Yet, in other geographies, which make up the majority of the world, there are more two-wheeled vehicles than four-wheeled ones. Lanes cannot be structured the same way they are structured in the U.S. When two-wheeled vehicles are the majority, lanes cannot be structured for cars. Traffic planning demands originality and innovation. Few governments recognize this mismatch in problem, space and solutions, and thus, diagnose this problem incorrectly.

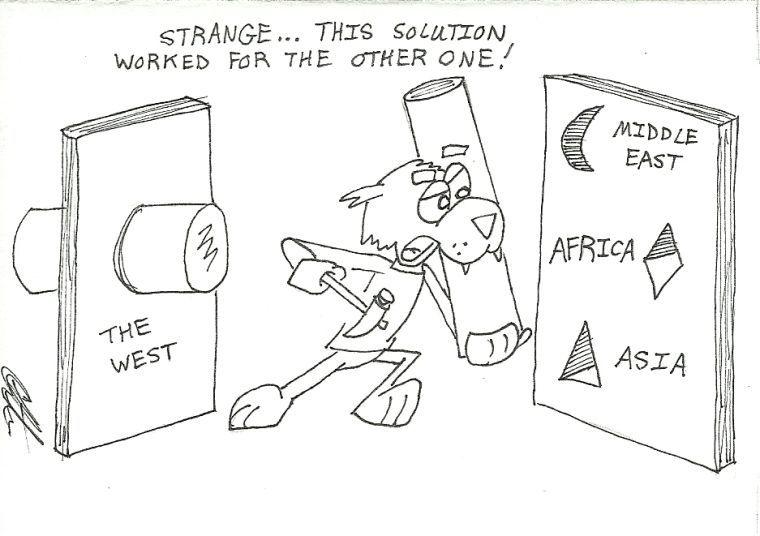

Technology must innovate. Most of the technological solutions are invented in the West, for the West. Blindly porting them to the East might help prevent some problems, but they cannot become cures.

For example, the modernization of a city into a metropolitan is a favorable trend in the West. Yet, most of the developing countries in the East are a distributed populace. The typical Eastern country consists of millions of smaller, rural communities. Metropolitanization of cities results in villages, drained of their intellect, migrating to the cities. But the cities are too small to accommodate the growing population and result in side effects such as lack of traffic sense, hygiene and space.

These are only the more visible side effects that are apparent to a skilled diagnostician. But there are other hidden ones that take their toll slowly, like rusting of iron. In the above context, this refers to the psychological adjustments that villagers who migrate to cities must go through, the pain of separation and exploitation by the hands of the rich and powerful.

I am not against development. But technology needs to understand the difference between the development models of the East and that of the West.

Problem spaces change drastically across hemispheres, too. Africa has problems that need a kaleidoscopic viewing. Multifaceted and intricate, the societal structure is not like that in the West. Religion, caste and color hold unequal weights as opposed to the uniformity found across the U.S. and Europe.

Technology cannot represent a master key. It will not fit into all the locks in the world, and it will take time and effort for technologists to understand the rises and troughs that open locks across different countries and continents.