A friend of mine has a father who served in the military during the Vietnam War. Both she and her father wish to remain anonymous. Her father once told her he doesn’t wear “Vietnam Veteran” hats, unlike some of his fellow vets, because he is not proud of his time in Vietnam. He doesn’t tell many people that he served at all for the same reason.

Though my friend’s father may not fit the norm, he surely is not alone. Many veterans have organized Veterans For Peace, a global organization intent on putting an end to war and reclaiming the anniversary of the armistice of World War I on Nov. 11 as Armistice Day—a day of peace as it was originally intended.

Instead, Veterans Day is just another reminder of his darkest years and the mental anguish they caused him.

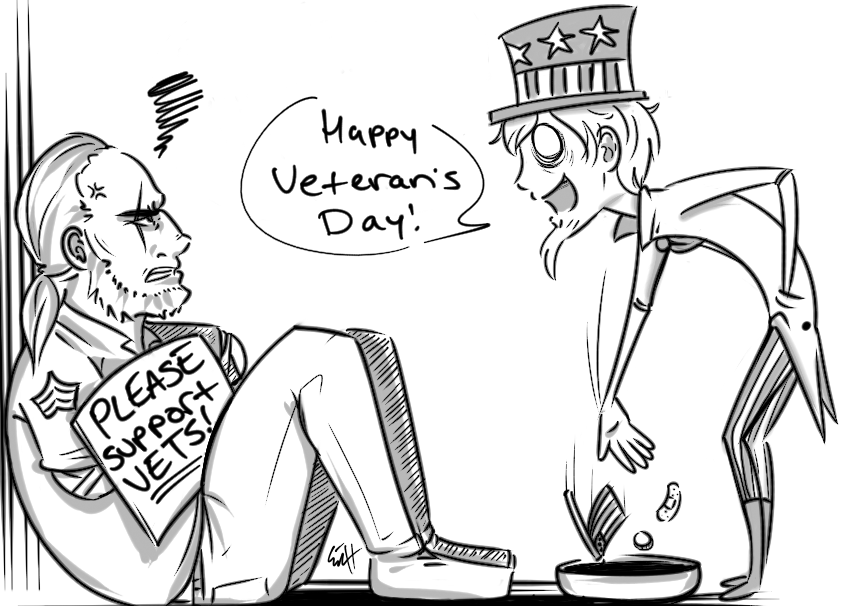

In the context of a government that does next to nothing for returned soldiers, Veterans Day comes as nothing more than a consolation prize for a contest no one signed up for.

Merely waving around a United States flag, shouting, “I support the troops!” is not only in bad taste, but is entirely vain, self-promoting and appropriating. Sure, if someone donates money regularly to veterans’ funds or volunteers to help with post-war treatment, that person can absolutely wave that flag and shout whatever mantra desired.

As it is celebrated now, Veterans Day is nothing more than a fraying and cheaply made United States flag ready for no one in particular to wave around. The nation as a whole has more in common with someone who doesn’t give two thoughts about the troops except to wave a flag on Veterans Day and Memorial Day. Our federal and state governments are the biggest hypocrites of them all (what a surprise).

The Veterans For Peace site features a counter demonstrating the fiscal cost of war since 2001. It suggests war has cost the United States more than $1,586 billion—and counting. The organization proposes, instead, we spend this money toward peace efforts and treating veterans.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs claims it offers treatment for PTSD and other combat-related injuries to all veterans who completed active military service, active duty for training, inactive duty training or were discharged “under other than dishonorable conditions,” as well as to National Guard members who completed deployment to a combat zone.

Though Veterans Affairs offers these services, they are not enough. Across the country, veterans receiving treatment were victims of malpractice, faulty or contaminated equipment, and have sometimes died due to medical neglect, according to Michelle Malkin of the National Review.

Likewise, veterans often encounter unemployment upon returning home. CNN reported 77 percent of veterans have dealt with problems of unemployment in their lifetime, reaching up to 15.2 percent at a time. Currently, 7 percent of veterans face unemployment—as opposed to the national unemployment rate of 5.8 percent.

Beyond that, more than half of the soldiers returning from Iraq will face homelessness for at least two years, according to Veterans For Peace.

All of these problems and statistics paint a grim picture for veterans. But at least they get a whole day to reflect on their time overseas and all the horrendous things they encountered.

It would be remiss of me to propose a problem with no solution. The US Veterans Initiative recommends donating money to pro-veterans associations. Some well-established associations include Disabled American Veterans, which offers myriad ways to help soldiers who have been disabled, and Homes For Our Troops, which utilizes volunteers toward building and adapting homes for injured veterans.

The Wounded Warrior Project, too, is a phenomenal organization that helps veterans receive rehabilitation and counseling. This Thursday, NC State’s chapters of Sigma Alpha Epsilon and Alpha Delta Pi are partnering with Groucho’s Deli to raise funds for the Wounded Warrior Project.

Helping can be as simple as stopping by a deli. It is important we all do our part to support United States veterans before we appropriate their day for the sake of empty patriotism.

Erin Holloway is a senior in English and anthropology