Few assertions are more aggravating than, “This is America; we speak English here.”

One summer afternoon, as we ate at a pizzeria, my mom mentioned occasionally feeling uncomfortable speaking in Spanish because she thought it attracted attention. At restaurants, my parents and I tend to speak Spanish to one another at the table. When the waitress or waiter comes near, we order in English, say please and thank you. Back in our own conversation, we revert to Spanish.

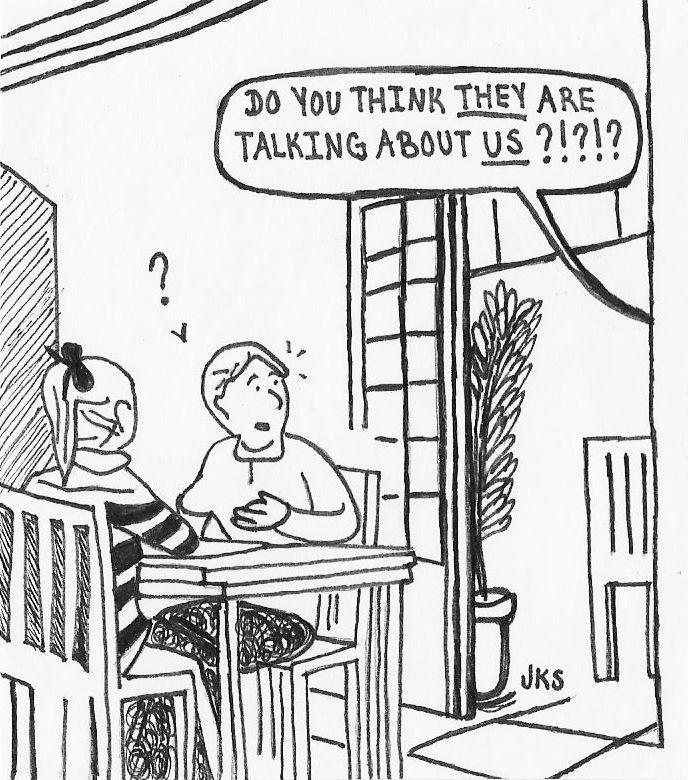

Perhaps due to my oblivious nature, I had never felt uncomfortable speaking Spanish in public, but as she said that, I looked up and noticed for the first time the faces of those surrounding us.

For the most part, they looked uninterested, conditioned to ignore the conversations of those around them. Some smiled politely. A small fraction looked back at me with a sort of quiet resignation.

I understand that at times it’s uncomfortable to hear people speak in another language. It’s not out of the question that we may be plotting your extinction and are speaking in another language to conceal our plans. Plus, why should you be the only one who has to whisper to have a private conversation in public?

Valid points. I get it, I really do. It’s irritating to have something unfamiliar in the place you call home and have it become normal without you having a say. I guess you could say that because we chose to be here, we have the option to leave if things aren’t the way we like them.

Though it’s only superficially true that most immigrants decided to come to the United State of their own free will, it’s hardly true that we did so because we wished to forget our native cultures. It’s even less true that we want to cause you discomfort where you feel at home.

This isn’t an argument about immigration or assimilation or anything of the sort. It is a plea for all of us to grant others space and consideration to keep a part of themselves—whether it be their language, gender-identification, music taste, sexual orientation, whatever—intact, regardless of how we personally feel about it. That is the only way we’ll coexist happily. My plea is about recognizing that “they” are only “they” because we have chosen to separate ourselves from “them.”

I had the chance to hear Dr. Ophelia Garmon-Brown tell a story of how she became the first North Carolinian African-American female to graduate from medical school. I was touched by a simple piece of advice she offered us minority students: Stand tall only because you stand on the shoulders of those before you.

When I speak Spanish to my parents at Angelo’s Pizzeria, it’s not to leave you out. It’s to retain some sense of my culture, to stand more proudly on the shoulders of those before me, so that we can all stand together.

Not something terribly complex, it’s a piece of advice that can really change the way one regards oneself in relation to others. If you do not allow others to stand tall too, you stand alone.

Consider that in asking us to abandon part of our identities: We become less of a “we,” and more of two opposing forces pulling at each other. “You” and “I” both attempt to drag the other to the opposite side, when it would be more pleasant to just agree that “we” can share in being different.

So yes, this is America. But to claim that “we” speak any language only makes sense if we start thinking and acting as a communal and united “we.”