The last two months have seen the death of Michael Brown, 18, killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri; Ezell Ford, 25, who was killed by a police officer in Los Angeles; Frank Alvarado, 39, killed by a Salinas police officer;Eric Garner, 43, killed by a New York police officer. Marlene Pennock, 51, was brutally beaten by a California Highway Patrol officer. These incidents all have two things in common: all of these victims were unarmed and of color.

Of course, the majority of police officers has honorable intentions and earned the utmost respect for carrying out their duties as justly as possible. However, recurring headlines in recent years suggest there is a growing problem of abuse of enforcement power.

USA Today carried out an analysis of FBI data from the last seven years, which concluded that approximately a quarter of the 400 annual deaths delivered to federal authorities by local police departments were white-on-black shootings. Compare this to almost two black suspects killed a week by white police officers, averaging 96 accounts per year. Undoubtedly, this is an alarmingly high statistic, and real change needs to be put in place or the protests in Missouri will only continue to escalate.

One option that has the potential to be implemented nationwide is the use of video cameras for police officers to wear on duty. This has already been successful in Rialto, California, where they conducted a controlled study requiring officers to wear a small camera that filmed all their interactions with the public on a daily basis. After one year of recording, complaints against the Rialto police decreased by 88 percent. Additionally, the use of force by officers on duty fell by almost 60 percent.

Although the results are indisputable, it may be too expensive to supply entire forces with devices. The excessive costs come from the storage and management of the data they generate.

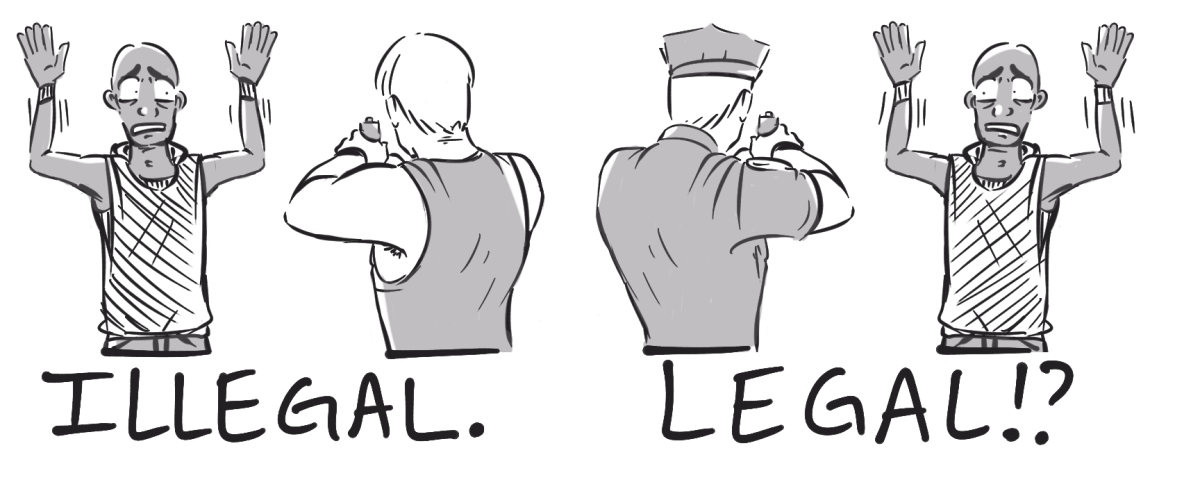

An alternative solution that perhaps does not involve as many resources is the expansion of the legal definition of reasonable use of force. The U.S. Supreme Court defined reasonable use of force in 1989 as force “judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene, and its calculus must embody an allowance for the fact that police officers are often forced to make split-second decisions.”

The problem arises when law enforcement agencies narrowly interpret that definition to mean the rationality of the force is restricted to an assessment of only the amount of force used in the moment. This means that the behavior of the officers in question immediately beforehand is never taken into account, and, therefore, the behavior of officers who provoke their victims is excused.

There have already been instances of broadening this definition as to hold officers more accountable for their actions. Earlier this year, the Seattle Police Department and the Los Angeles Police Department did just that.

The updated law in Seattle now prohibits officers from engaging in physical force “against individuals who only verbally confront them unless the vocalization impedes a legitimate law enforcement function or contains specific threats to harm the officers or others.”

Similarly in Los Angeles, the practice of deadly force now requires “consideration of not only the use of deadly force itself, but also an officer’s tactical conduct and decisions leading up to the use of force when determining its reasonableness.”

Both of these measures are necessary to prevent more senseless acts of violence against unarmed black people. It certainly seems like the time to be policing the police, lest the protests carried out in Missouri are a taste of bigger things to come.