Let’s face it: As much as we love to waste time on it, Facebook is a pretty offensive place. Sexism, racism, homophobia and general animosity seem to flourish behind the anonymity of a computer screen. So among all of the potentially objectionable material that floats unchallenged on social media, what perplexes me most is the magnitude of offense the Facebook community took to a certain Texan cheerleader with an unapologetic enjoyment of big-game hunting in Africa.

With that perfectly practiced cheerleader smile eerily juxtaposed against the bodies of slain Savannah creatures, you cannot deny the unsettling quality of the trophy pictures, which once populated Kendall Jones’ now vanquished Facebook page. But as the late writer and filmmaker Susan Sontag wrote in her infamous essay about the rhetoric of war photography, we shouldn’t underestimate the inflammatory effects violent images have on us.

As mortal beings, we don’t like to acknowledge the truth: Pain and death are natural and inescapable parts of life. So, when confronted with images of such things, we “are sure that the right is on one side and injustice is on the other,” as Sontag wrote.

But the divide between good and evil seldom exists as clearly in the real world as it does in Disney movies, for instance. As Sontag points out, we can’t allow the emotions aroused by graphic images to supersede logic and distract us from probing deeper into the issues underlying such photographs.

I’ve been an animal science student for too long to suppose that there is ever a straightforward position regarding animal welfare issues. Though I don’t hunt, I recognize that hunting, when done responsibly and with respect for the animal and its environment, helps keep wild populations at manageable numbers. Often, hunting prevents famine and disease, which overpopulation can foster. In Jones’ case, however, we aren’t talking about bagging a few ducks or bucks — we’re talking about the trophy hunting of critically endangered African species.

Though one would think that every life is critically important to the conservation of threatened species, the reality is actually much more complicated. In wild populations isolated by human development, it is often necessary to remove animals strategically to maintain sufficient genetic diversity and to protect limited resources.

This is where trophy hunters come in. Currently, 23 African nations permit sport hunting, which, through the sale of permits to an estimated 18,000 hunters, cumulatively collect more than $200 million per year. For comparison, the non-profit World Wildlife Fund only takes in $685 million per year to divide among conservation projects globally, according to James Delingpole of The Telegraph. Furthermore, the ecotourism dollars generated from such hunting trips are credited for breathing life into otherwise isolated rural economies, which can help to reduce dependency on bush meat and curb the loss of wildlife to illegal poaching.

But have we seen results? Again, the answer is complicated. Mismanagement in the allocation of hunting permits has been implicated in the significant decline of Tanzania’s lion population. However, when applied correctly, the progressive effects of trophy hunting cannot be ignored. A 2005 paper from the Journal of International Wildlife Law soundly accredits the legalization of White Rhino hunting in South Africa for the restoration of the species, and since elephant hunting was legalized in Zimbabwe the amount of land dedicated to wildlife management has more than doubled.

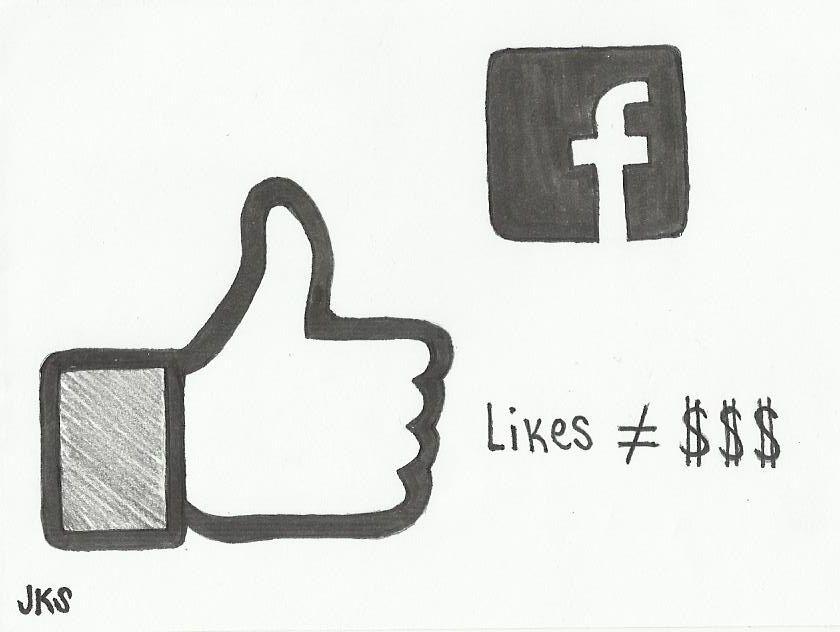

Shaming hunters on Facebook has done nothing to support endangered species. So, before we join the call to arms to eradicate such unsettling images from your Facebook feed, we must not forget: Likes or comments on social media platforms don’t save these species from extinction, but cash, including blood money from trophy hunts, has and will continue to do so.