From my earliest days in the United States public education system, the concept of the American dream was touted as the country’s calling card. I, like many of my peers, had grandparents or great-grandparents who had left other nations in search of something better. My own grandfather’s family left Russia prior to the Russian Revolution, knowing that life in the U.S., in many ways, would be more difficult than the place our family had lived for hundreds of years. But what made the move a reality was the hope that even through the language barrier and unspoken segregation into cities and towns supporting similar populations of people, there was an opportunity to change social status and financial standing through hard work. In Russia, my family’s fate was largely predetermined. In the U.S., the possibilities were, in theory, endless.

A little less than 100 years after my great-grandparents left Europe, by almost all accounts, my family had achieved the dream. Both of my parents are wage earners, and I am attending a four-year university. My education offers me the chance for upward mobility, and if it were not for the hard work of my elders throughout the entire 20th century, I would have a more difficult time attaining the education that, for the most part, is so vital in today’s society for prosperity and quality of life. The concept of the American dream is still meant to hold true, however, for those immigrating to the U.S. today. What’s changed in 100 years?

The U.S. has never been a socialist state, and is not one today. Capitalism has driven the U.S.’s economy since its conception as a nation, under the pretense that a capitalistic nation does not stifle the business giants, job creators and creativity that are crucial to the expansion of an economy. This is true—to a point. Completely unregulated capitalism is not an American value. Regulations exist for the purpose of not allowing gains to be made by one person or corporation at the expense of another. Yes, corporations exist to make money, but when they do so as entities protected by the U.S. government and allowed to pay meager amounts in taxes while becoming bloated with unfairly accumulated capital, the poor get poorer. I am continually amazed by political candidates, from both sides of the aisle, who claim to stand for the small businesses and independent innovators, while failing to address legislation that allows massive corporations to pay mere slivers of their determined income taxes. Small businesses aren’t getting these tax breaks, and neither are the families who run them.

What does this have to do with those working to achieve the American dream today—those new immigrants to the U.S. and families trying their hardest to break out of poverty? It boils down to whom our current system favors in its design. Over the previous century, the U.S. quickly passed through the so-called “golden age of capitalism” following World War II into the age of Reagonomics, which loosened the reigns of regulation in the name of free enterprise. The socioeconomic gap between wealthy and poor has widened to the point of no return. The Economist reported this week that a whopping 95 percent of gains from the economic recovery post-2010 crash have gone to the richest 1 percent of earners, meaning the divide between wealthy and poor is at its highest level in a century. The magazine phrased it best: “Although some degree of inequality is good for an economy, creating incentives to work hard and take risks, the recent concentration of income gains among the most affluent is both politically dangerous and economically damaging.” We have passed the point of inequality being good for the growth of our nation’s wealth. Now, we are in a constant loop of feeding the monster of income gap.

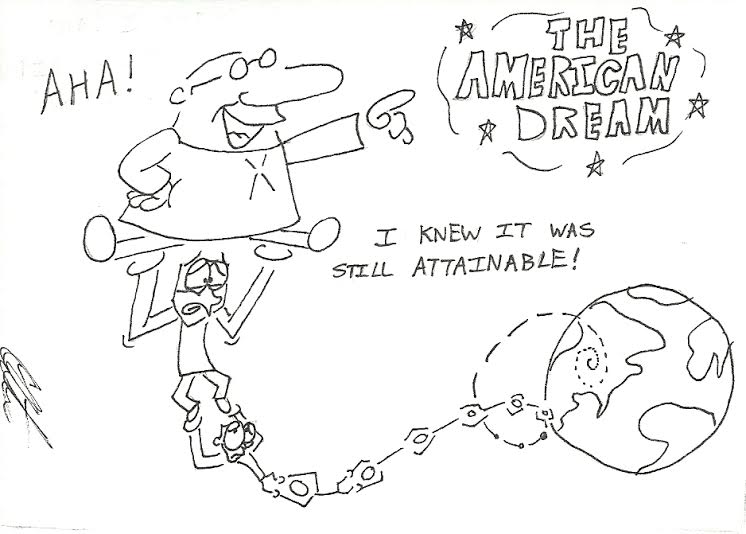

The idea that those born poor are destined to be poor, and are always poor by their own fault, is, quite frankly, disgusting. The system is flawed. Those who scoff at the fight to close income inequality and cry out in the name of unregulated economic enterprise, it seems, are almost always doing well financially. It is all well and good to make sweeping generalizations about those struggling to break out of the mold the failed system has built around them from a position of relative economic stability. It is easy to say that those failing to move upward are simply not trying hard enough, or that they do not possess the skills necessary to succeed. Some do not. Equality of outcome is not guaranteed, nor should it be. Equality of opportunity, however? Absolutely. The ugly honest truth is that for many, many people, their cards were marked in the name of unregulated American capitalism years before their birth. Those who have been cheated by the system know the American dream isn’t attainable by virtue of our economic values, at least not in the same context it was 100 years ago.