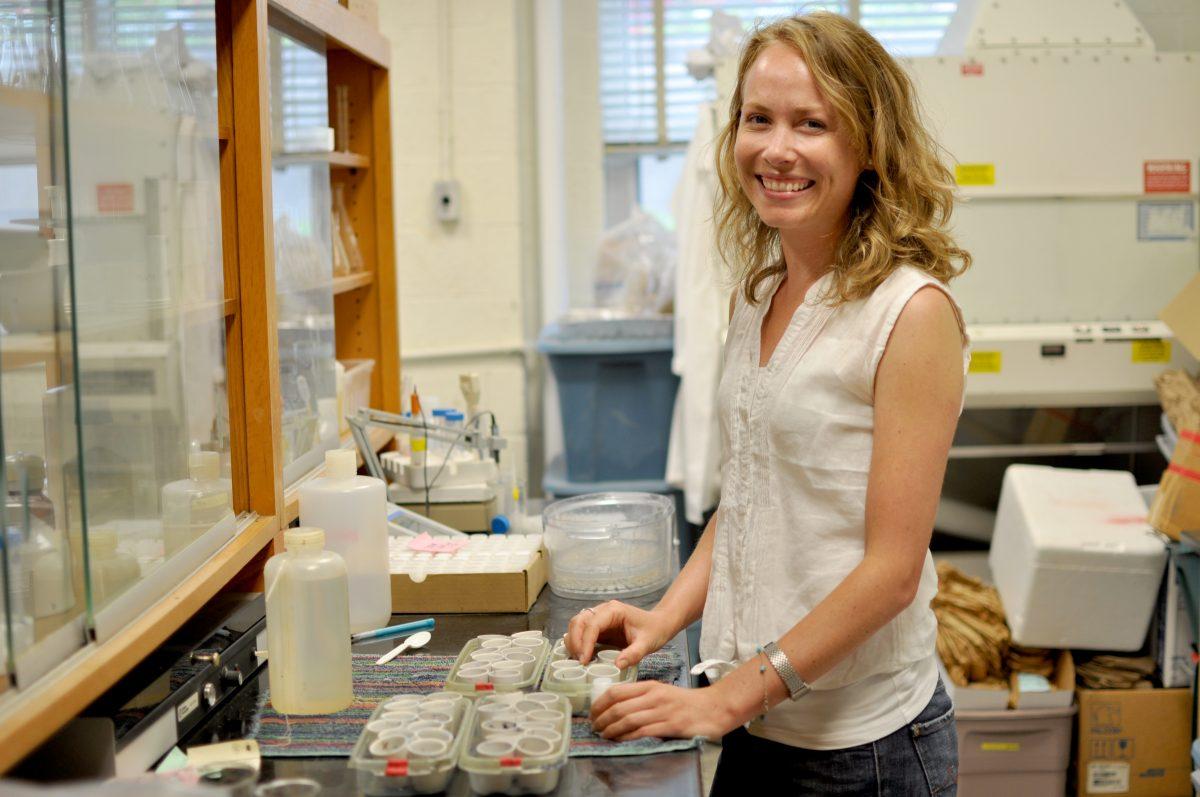

At the rate of producing 10 to 15 tons of strawberries per year, North Carolina ranks third in the nation in strawberry production, but the state may one day become even more successful through the work of N.C. State crop science doctoral student Amanda McWhirt.

McWhirt’s project emphasizes the use of summer-cover plants, vermicomposting, which is the practice of using worms to naturally improve the soil, and inoculants, which can improve overall soil health in a sustainable way and lead to better strawberry yields.

The National Strawberry Sustainability Initiative funds McWhirt’s research through the University of Arkansas.

McWhirt is conducting the research at the Center for Environmental Farming Systems, the largest facility in the region dedicated to sustainable agriculture research, outreach and education. It’s run jointly by N.C. State, N.C. A&T and the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Michelle Schroeder-Moreno, an assistant professor of crop science who serves as McWhirt’s adviser, said the work is based on eight years of previous work in organic strawberry production.

Strawberry farmers previously relied on methyl bromide fumigation to rid the soil of unwanted pests that killed the strawberries, according to Schroeder-Moreno. However, the issuance of the Montreal Protocol called for the phasing out of the fumigant due to its effects on the ozone layer in countries participating to the treaty, which includes 196 countries, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

In 2005, methyl bromide reached “100 percent phase-out” status, though the phase-out exempted strawberries under the critical-use exemption because strawberry growers didn’t have many alternatives when compared to other crops, according to the EPA. The state has since halted production of methyl bromide, according to Schroeder-Moreno.

“It was banned completely in the U.S., but strawberry growers could keep using it for a few years, and now it’s where no one should be using it, but there is still some out there where people are using it kind of under the table,” McWhirt said.

McWhirt adds organic matter and diversity to the soil, and because the technique already worked for other crops, it made sense for it to work with strawberries, according to Schroeder-Moreno.

“Amanda’s research is really, I think, the pinnacle of it because we’ve researched these sustainable soil management practices, but we haven’t really done it separately and with or without fumigation,” Schroeder-Moreno said. “Change is hard for producers, it’s costly, and so we really not only wanted to show the yields, but also the economics of what it would be to take on some or all of these practices.”

McWhirt said she takes charge of running the field studies at CEFS, which will entail two years of data collection and lab analysis.

Once the field studies are complete, McWhirt said the project would move to on-farm trials. She will be working with three different producers: an industrial-scale producer, an organic producer and a small grower.

McWhirt tries to communicate with strawberry growers and the community through articles, a Facebook site and hosting a webinar, according to Schroeder-Moreno.

“We’ve done a lot of outreach with potential growers,” McWhirt said. “We made a video that kind of explains the vermicomposting and how we incorporate the vermicomposting into the production system.”

Schroeder-Moreno said the research also serves the community, as McWhirt delivers some of the strawberries to the N.C. Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program.

McWhirt said she still has to balance her classwork with research. That’s especially challenging during strawberry season when she spends more than 40 hours a week working on the project.

“Besides eating a lot of strawberries, I’ve actually enjoyed doing a lot of the field stuff,” McWhirt said. “It’s a lot of work, but I have a lot of people who help me that are really great, and so it’s fun to go out and get out of the office and dig in the dirt and do that kind of thing every once in a while.”

McWhirt said she also works with undergraduate student workers Sarah Wiebke and Austin Wrenn.

“I know I was a student worker when I was an undergrad, and so that’s probably what got me thinking about graduate school originally and thinking about doing research,” McWhirt said. “So it’s interesting now to be kind of full circle and have student workers working for me because I can see them start to get interested or decide if they like it and they get the same experience. I think it just adds to your education because otherwise you’re just taking classes and, you know, professors have this other side that they’re doing. You don’t really know what they’re doing, and so it’s good to actually participate in that part of the University.”