The most expensive games

The most expensive games

Julie Smitka, junior in physics and philosophy

" />The most expensive games

Julie Smitka, junior in physics and philosophy

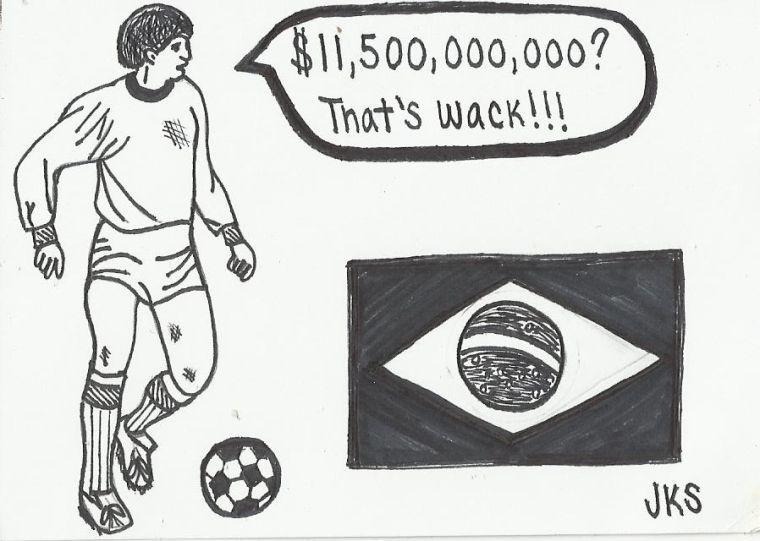

The World Cup is well underway in Brazil. As well, there is much unrest spreading throughout the country. There have been protests for the last year about government priorities and the spiraling costs of the tournament, which is estimated at $11.5 billion. Many Brazilians have demanded “FIFA standard” hospitals, schools and public transportation, rather than just stadiums.

The government foolishly anticipated that the population would forget about its woes once the tournament began. The error of its way was exposed when activists from the Homeless Workers Movement marched on the São Paulo stadium, where the hosts kicked off the tournament against Croatia. Riot police used tear gas against the indigenous dissidents. The hacktivist group, Anonymous, has threatened cyber-attacks against World Cup corporate sponsors, and public transport workers in São Paulo have carried out strikes that gridlocked the city.

The objections of the people are reasonable, as despite Brazil’s progression into a major economic super power, social development has been depressingly slow. About 35 percent of the population lives on or below the poverty line, on less than $2 a day, a disconcerting statistic for a country attempting to prove itself as a developed society.

The 2000s saw an economic boom that mainly affected two groups. The very wealthy experienced an immense increase in their wealth, whilst the lives of Brazil’s poorest were also transformed. Despite this, the last 10 years have included a string of poverty and hunger-reduction programs as part of the Bolsa Família social welfare program that has resulted in the greatest decline in hunger and absolute poverty the country has ever seen. The increasing help for the poor raises the question as to what has triggered the huge scale of protest that is evident during the tournament.

The unrest has stemmed from the middle classes, who believe they have not profited at all from Brazil’s economic development. Social policy has been controlled by the macroeconomic conservatism of the administration so that public healthcare and education have persisted to be drastically underfunded.

The protesters in Brazil have expressed that the $11.5 billion spent on the World Cup should have been more sensibly used toward improving vital public services. According to a Pew Research Poll, 61 percent of Brazilians do not think hosting the World Cup is worthy of celebration. Instead the people of Brazil view hosting the tournament as a perfect opportunity to protest against a vast range of issues affecting the country.

The situation in Brazil indisputably links politics to sport, as great sporting events so often do. There is a lot of frustration from the people at the government’s lack of will power to tackle corruption and the “entrenched elite” that dominate Brazilian politics and business.

As demonstrated in Sochi, global attention as a result from a sporting competition brings to light concerns that affect the country as a whole. It also raises speculation as to whether it is appropriate to abandon spending on vital public services to instead devote large amounts of money on sporting events.

There is no simple answer. The long-term benefits of a World Cup and the Olympic games are unpredictable. Regardless of Brazil’s dominant economic position in the world, in terms of globalized popular culture, Brazil’s presence is negligible. The government hopes to expand the brand identity of Brazil in the global tourist market by hosting the two major sporting tournaments.

The World Cup has allowed Brazil the chance to reform whilst presenting its people an opportunity to express their resentment at the regime in the spotlight of the world. Undoubtedly, the level of funding for the World Cup is excessive, but perhaps the great power of sport will help the people of Brazil get their message across to the government. As a spectator, it would seem that the protesters, too, make up a team worth rooting for.