The Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies received a $476,483 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to support its project of digitizing and making accessible archival materials from Lebanese immigrants.

The mission of the Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies is to preserve the history of Lebanese immigrants in the United States and other parts of the world and to share their stories and histories with the public.

Akram Khater is the director of the center and a professor of history. He said the center has been collecting and preserving archival materials since it first opened.

“For the past seven years from when the center was established, we have been building an archive of these memories, stories and histories,” Khater said. “The archive includes anything from the first Arabic newspapers published in the United States, in North and South America really, to letters — family letters back and forth to Lebanon — to photographs, audio recordings, home movies, objects, books, textiles, clothes, anything you could think of that was really a part of their lives and experiences as people who left the Eastern Mediterranean, the Middle East area.”

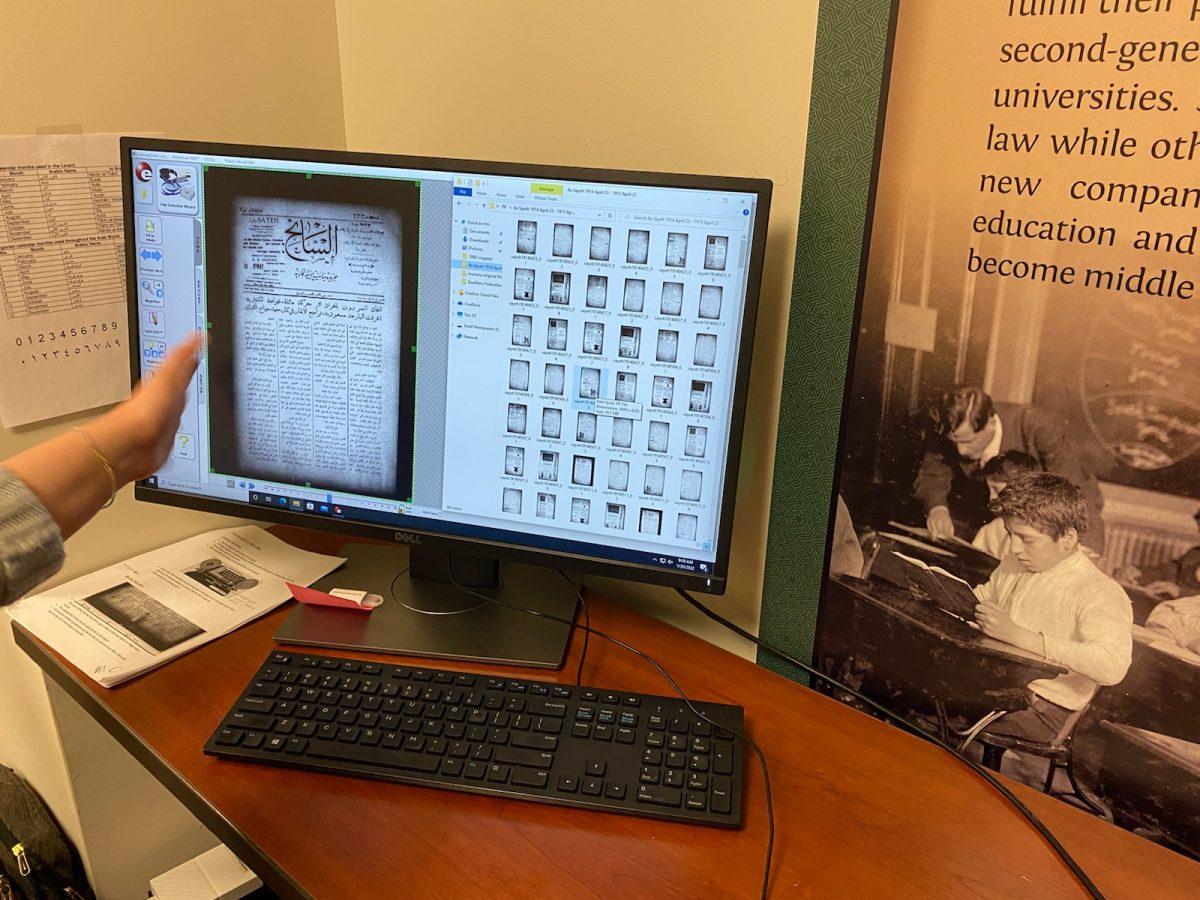

The grant the center received will go towards a phase of an ongoing project using a character recognition system developed by the center. The project addresses the challenge of going through digitized PDFs and not being able to search for specific words and phrases in Arabic like one could for a document in English.

“When we digitize things, we make an image of them,” Khater said. “The problem is because they are in Arabic, you cannot really search through them. For us to have, let’s say, a quarter million pages and to try and go through those quarter million pages becomes a chore, so one of the first things we want to do was to create something called Optical Character Recognition System (OCR). So, we developed our own system here, and we started working on this project about three years ago. So, I can take an image of a newspaper and turn it into a searchable text. Rather than just an image, this becomes a text, and I can search within the text.”

Khater said OCR makes doing research a lot faster.

“Just to give you an idea, when I did my first book, I sat at the New York Public Library using Arabic paper microfilms for about six weeks,” Khater said. “I’m a terrible researcher. I lose my patience very quickly. But, I would sit there going page by page looking for material that I wanted for my book. When we developed this, I typed in some of the search terms that I used at the New York Public Library and in 30 seconds, it pulled up everything. So, six weeks to 30 seconds.”

Once the OCR was set up for documents in print, Khater said the people at the center realized a lot of the material they were adding to the archive was handwritten. The center applied for the grant with the intention of furthering the recognition system to identify handwritten words and phrases.

“You can tell this is very different than print,” Khater said. “Human beings when they write, they write in very eccentric ways. We all have our different ways of writing ‘hey’ in English. … We thought that the next logical step for us was to go from newspapers and books that are printed to handwritten text recognition. In other words, to develop a system that takes this image, processes it and then recognizes what each word is and then you can search them. When we applied for the grant, we applied to do exactly that from the National Endowment for the Humanities. I think, for us, it will really revolutionize research in Arabic.”

The Arabic OCR project is reliant on student participation.

“Students have always been integral to this,” Khater said. “We’ve had about three or four generations of students that have been employed and working at the center in computer science. We also have history students who work with us and undergraduates as well. Their work entails collecting material so that we can process it. A lot of the research we do here is dependent on student participation and work.”

Rachel Acker is a third-year studying history and Arabic studies. She is also an intern at the Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies.

“My job as an intern, specifically, is to make the archives a little bit more accessible, make them easier to understand,” Acker said. “So, [Amanda Forbes], who is my boss, she is the archivist here, but I do a lot of work trying to organize information. We worked on several different projects trying to do that. Just trying different spreadsheets with death certificate records and whatnot. For this specifically, what we’re doing is taking microfilm that has been uploaded. We’re trying to edit it to make it a little more legible because the microfilm is not the best.”

Acker said receiving the grant is important for the center as many of the workers there are grant funded.

“Funding is so important for this type of work,” Acker said. “In order to continue doing this work, we have to be able to have funding so that I can have my position. I’m actually a grant funded position. A lot of positions here are grant funded and so in order to make the information accessible, we have to have capital. So, this is so incredible that we were able to receive this.”

Acker said she wants the NC State community to know about the Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies.

“I’d like the NC State community to know that we’re here,” Acker said. “Unless you’re involved in Arabic Studies and the Middle East, nobody knows we’re here. And I think what we do is important work. I am just a small part of the work and, even on a large campus, we’re a piece of the puzzle and so, if people stop by and just say, ‘Hey, what do you do?’, we’d love to talk to them.”

Khater said the center is likely to be looking for students to translate Arabic soon to further develop the recognition system.

“We will probably need a lot more students that know Arabic real well, or well enough, to transcribe,” Khater said. “Basically, not only do you have to divide the image into segments, but then you have to tell the computer what’s in each segment. The only way for the computer to know is if you give it training. In other words, we will need students to take let’s say 1,000 lines of Arabic and transcribe them manually so then the computer knows ‘Ah, okay, I know what you’re saying to me. This equals this.’”

Those interested in getting involved at the Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies can get in touch with Khater or stop by the center in Withers Hall, Suite 332. Learn more about the center at its website lebanesestudies.ncsu.edu and about the Arabic OCR project through arabicarchives.org.