Out of all the voluntary services one can perform, very few compare to the act of giving blood. Every year, 4.5 million people nationwide need a lifesaving blood transfusion, including patients with cancer or traumatic injuries. The decision to give blood is also a decision to protect lives, and a single donation can save up to three people.

In January of this year, the American Red Cross declared a national blood crisis, which the organization attributed to decreased donor participation and mass blood drive cancellations. Despite the ongoing need for blood in the U.S., one group is consistently denied the opportunity to donate: men who have sex with men (MSM), and it’s high time for that to change.

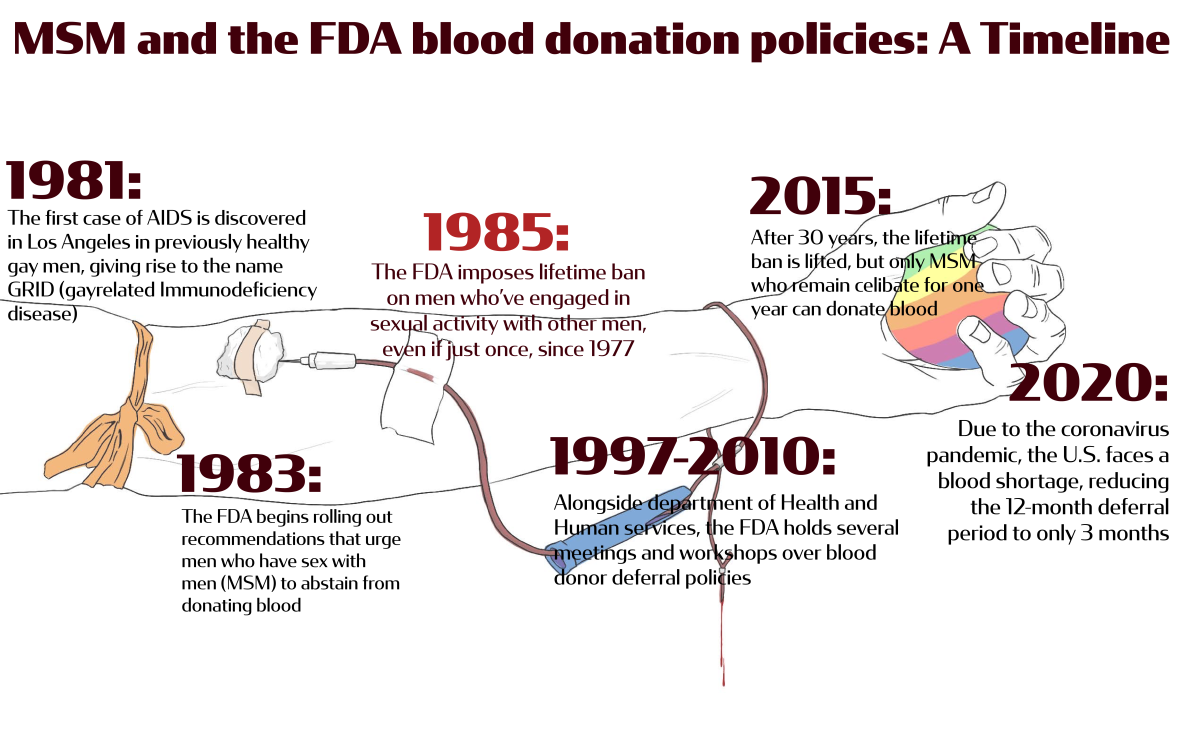

The current FDA policy is a remnant of the early 1980s, when the HIV/AIDs epidemic first took hold in the U.S. When it was discovered blood could transmit the virus in 1983, the FDA rolled out recommendations that deferred high-risk donors, which mainly consisted of gay and bisexual men. These recommendations became official in 1985, when MSM were permanently banned from donating blood.

At the time, the lifetime ban was arguably necessary, as little was known about HIV/AIDs, other than how it disproportionately affected MSM. In addition, no effective treatment existed, and testing for the virus was a lengthy process with unreliable results.

The ban was partially lifted 35 years later in 2015, and MSM were granted the ability to donate blood on the condition they remain abstinent for one year. In 2020, the deferral period was further reduced to three months in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, current testing methods can detect HIV, as well as other bloodborne diseases, well within a three-month period. For HIV in particular, the CDC requires donated blood to undergo two types of rigorous tests. One of those tests, the nucleic acid test, is able to provide a result in as little as 10 days.

With modern testing and screening procedures, it’s estimated that the risk of HIV transmission through blood products is one in 1.5 million. For comparison, the risk of infection in 1985 was approximately one in 10,000. While failures occur during blood analysis, overall, this process is far more effective than ever before.

In addition to being scientifically unsupported, the policy is rife with inconsistencies. One is the policy’s treatment towards self-identified males who have sex with men versus individuals with other gender identities. Under the current policy, someone assigned male at birth, who later identifies as non binary or a transgender woman, would be eligible to donate blood even if they have cis male partners. In this way, the policy neglects to make considerations for gender, creating an obvious loophole.

The policy also fails to account for individual differences in sexual behavior and unfairly discriminates against MSM in this regard. For instance, non-MSM who have had multiple sexual partners could be eligible to donate blood, whereas MSM in a monogamous relationship are denied outright.

For these reasons, several health and human rights advocates have pushed for a deferral system based on individual risk-assessment (IRA) rather than gender and sexual identity. In these kinds of assessments, donors are evaluated based on risk factors, such as number of sexual partners and drug use. Under an IRA model, low-risk individuals would be allowed to give blood, regardless of their sex partners.

Multiple countries have adopted this type of system already, including Spain, Italy, and more recently, the U.K. Research by the National Library of Medicine from Italy found that moving to an individual-risk based policy didn’t endanger the nation’s blood supply. Other countries have seen similar results, suggesting a gender-neutral approach to blood screening is not only equitable but safe.

For the U.S., transitioning away from a time deferral policy could not only add up to 600,000 more people to the blood pool, but it could also reduce stigmatization against MSM. The current policy perpetuates the myth that HIV is an inherently “gay disease” and MSM’s blood is dangerous. In addition to being homophobic, this type of thinking undermines progress towards overcoming the HIV epidemic, as discrimination can worsen health outcomes according to the CDC.

The call for an updated policy that doesn’t discriminate on the basis of gender and sexual orientation have long been made. In a time when doctors are forced to make decisions over which patients receive blood, it’s evident a change is long overdue. At this point, it’s no longer a matter of doing the right thing — it’s a matter of saving lives.