“What are you?”

It’s a question that has tested me for the past two decades. Explaining my identity to others has become a routine, an unraveling of nested dolls, each layer revealing another question.

Out of simplicity — or maybe spite — I like to stress others out by asking, “You tell me. What do you think I am?”

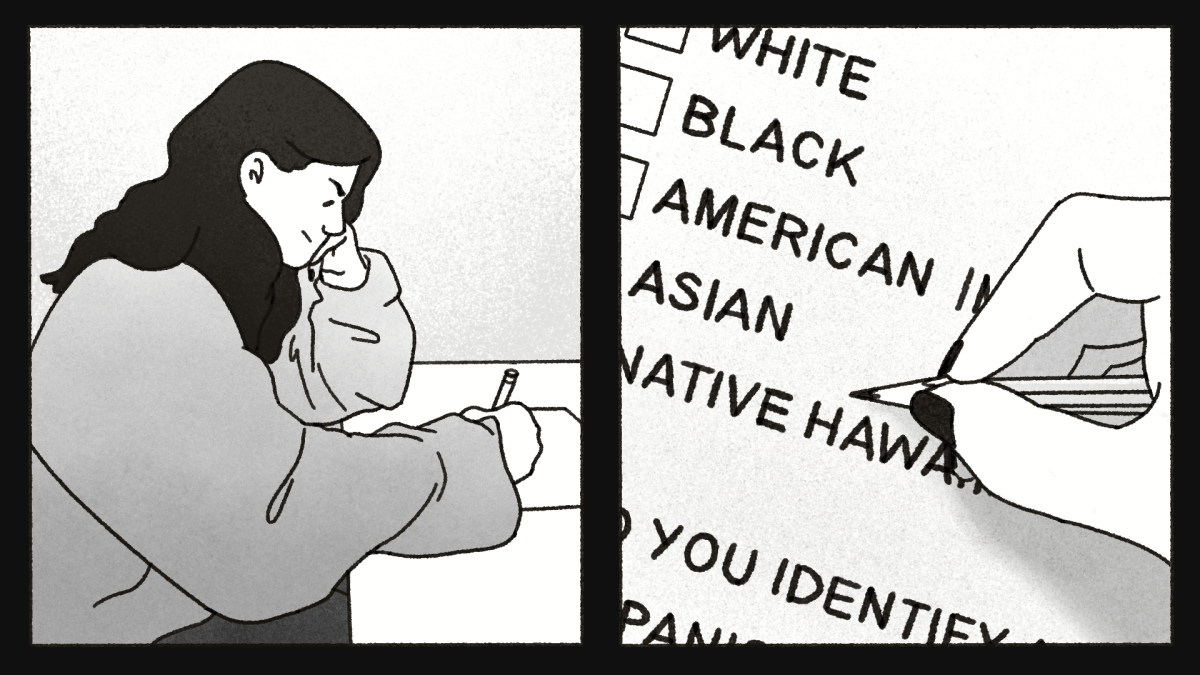

As an Guyanese-American person of Indo-Caribbean descent, the labels available to me have never quite fit. Filling out racial and ethnic information on official documents is a familiar nightmare.

White? Check. Asian? Check. Asian Indian? Well, technically.

Most of the time, I end up defaulting to “Prefer Not to Answer.”

When I tell people I’m Asian, their eyes narrow in confusion. My family is Indo-Caribbean; ethnically Indian, but not from India. Guyana complicates the narrative further — a South American country with Caribbean cultural ties, neither Hispanic nor widely recognized. The census forces me to choose one box: Asian. But marking that box feels like a half-truth.

Indo-Caribbean people are often erased from the broader Asian narrative — a reminder that the diaspora is more fractured and diverse than the categories we’re expected to fit into. My ancestors were Indian indentured laborers, brought to the Caribbean under British colonial rule.

That history isn’t widely taught, leaving people like me to explain ourselves over and over again. Even then, the explanation feels incomplete.

One of the strangest parts of navigating my identity is the shadow of Jonestown. When I mention Guyana, people either don’t know where it is or immediately ask, “Are you familiar with Jonestown?”

No. Heavy on the sarcasm.

The Jonestown massacre looms large in American memory, reducing an entire country to a singular tragedy. It eclipses the vibrant culture, resilience and history of Guyana itself. My family’s homeland is more than a single horrific event — but that’s rarely how others see it.

These experiences have made me hyper-aware of how the world perceives race and ethnicity; how people expect identities to fit into neat, predefined boxes. But the Indo-Caribbean identity defies those expectations. It’s a hybrid, a testament to resilience and adaptation. Yet the structures that define race and ethnicity in the U.S. rarely make room for people like me. My identity exists in liminal spaces; between continents, between races, between languages.

The older I get, the more I realize how important it is to keep explaining. If I don’t, who will?

The “Asian” box on the census doesn’t tell the full story. It doesn’t acknowledge the histories of indentured servitude, forced migration or the vibrant cultures that emerged from those legacies. It doesn’t account for the feeling of invisibility, of knowing you belong to a community that is rarely represented or understood.

To be Guyanese-American is to be a question mark in other people’s minds. But my identity isn’t something that needs to be simplified for the sake of others. It’s something to be celebrated in all its layered, complicated beauty.