The largest language learning model is humans, and I’m feeding my robot code of dramatic quarrels from “Love Island” and love professions from the classics here.

Is there more value in everything that happens before and after the profession of “I love you?” Like a car, the minute you purchase, its value diminishes each time it’s tossed around the block.

Reality TV confessionals break the fourth wall, speaking to the audience, coaxing them into rooting for them, seeing their inner workings and surrendering to their imperfections. Yet why are we surprised when Bachelor couples don’t work out, and why are we elated when fights break loose?

Scripted or caught in the act, what is this desire to see it all, entitled to connection with the figures on our screen, hate watching and hate to love, what is love doing on our screen?

Ludwig Wittgenstein was a philosopher concerned with communication who posited that good communication is about humility and discipline. He was also interested in what can and can not be communicated effectively; in this way, how do we describe love to each other, how do we profess it?

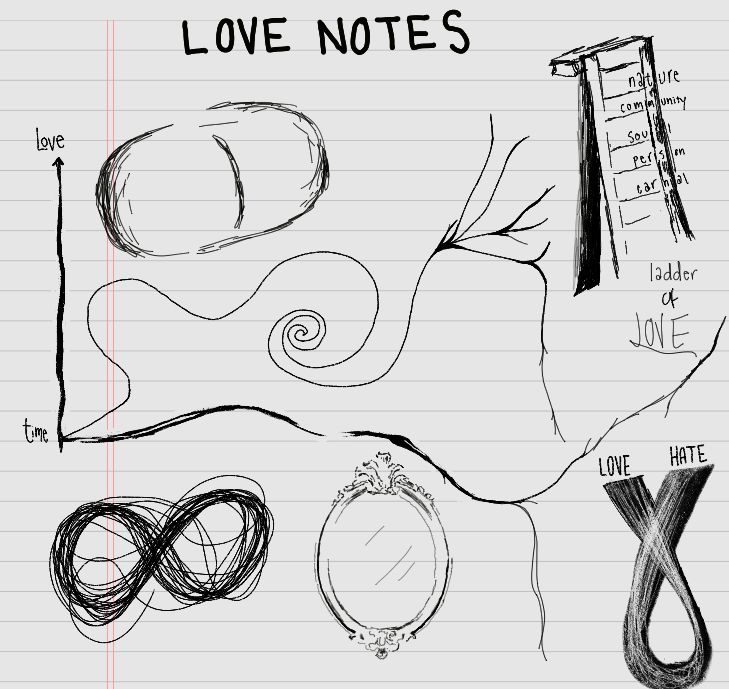

Plato’s Symposium prances around the idea of love — comedians, doctors, lawyers and more describe what love is in their eyes. The comedian posits love is a search for wholeness, fulfillment from reunification with the soulmate; the lawyer concerned with lust versus love; the doctor suggests that love is an equilibrium that exists in all things. Some say love is a spirit, a mediator between people and their desires.

Plato’s ultimate conclusion for what love is coined — Platonic love — is the idea that people rise through levels of closeness to wisdom and true beauty. It starts with the carnal attraction of bodies, then moves to the attraction of souls, and eventually union with the truth. In this way, truth, harmony, balance and nature seem integral to our ideas of love.

I’m concerned with how professions of love are depicted in media. Why did Glen Powell’s profession in “Anyone But You” flop, while “When Harry Met Sally” makes us weep? How does the spectator-prey dynamic in reality TV shows complicate our understanding?

Retelling Shakespeare’s “The Taming of the Shrew,” the film “10 Things I Hate About You” depicts, through tears, Julia Stiles’s character Kat Stratford proclaiming, “I hate your big dumb combat boots and the way you read my mind. I hate you so much it makes me sick. It even makes me rhyme. … But mostly, I hate the way I don’t hate you, not even close, not even a little bit, not even at all.”

Similarly, “When Harry Met Sally” discusses visceral responses to a significant other, Harry says, “I love that you get cold when it’s 71 degrees out. I love that it takes you an hour and a half to order a sandwich. I love that you get a little crinkle above your nose when you’re looking at me like I’m nuts. … And I love that you are the last person I want to talk to before I go to sleep at night.”

The art of noticing, the act of care, the integration of nurturing their nature is what makes these professions so compelling. It is the knick knacks and trinkets of someone, collecting oddities of another, being proclaimed and professed as truth, beauty, natural and just that captivates us.

So, I have beef with Powell, and more so with Will Gluck the writer, who plays the adaptation of Shakespeare’s “Much Ado About Nothing” in “Anyone But You” as “I love the way we fight. I love how smart you are. I love the weird way you stick your hands down my pants. And I love how you know what you don’t want.”

What is he even saying? Fluff, a display of grandeur performance in front of the Sydney Opera House upon helicopter arrival. He outlines general and not-so-astute observations, so maybe a profession of like or interest would be enough. It hits all the notes, but the flavors are unsavory. There is a lack of tension and a sense of unearned inevitability.

How do we reconcile the gap between productions of love and the realities we live in? What is love doing in our real day-to-day lives?

Lola Young’s “Messy” grapples with the lines between flaws and quirks, the spectacle of being loved and projected upon. I think this conflation of appreciating the individual unsavory is why we can see the thin line between love and hate, enemies to lovers; an imperfectly humane multi-dimensional feeling. In her rejection of her suitors’ projections, she sings an ode of self-love, reveling in her contradictory, complicated nature.

You can only know someone as well as you know yourself, and in this way, you can only love someone as much as you love yourself. We’re all just looking for ways to bend our time. Love or drugs — what’s the difference? As Murakami said in “Kafka on the Shore” — “Times rules don’t apply here. Time expands, then contracts, all in tune with the stirrings of the heart.”