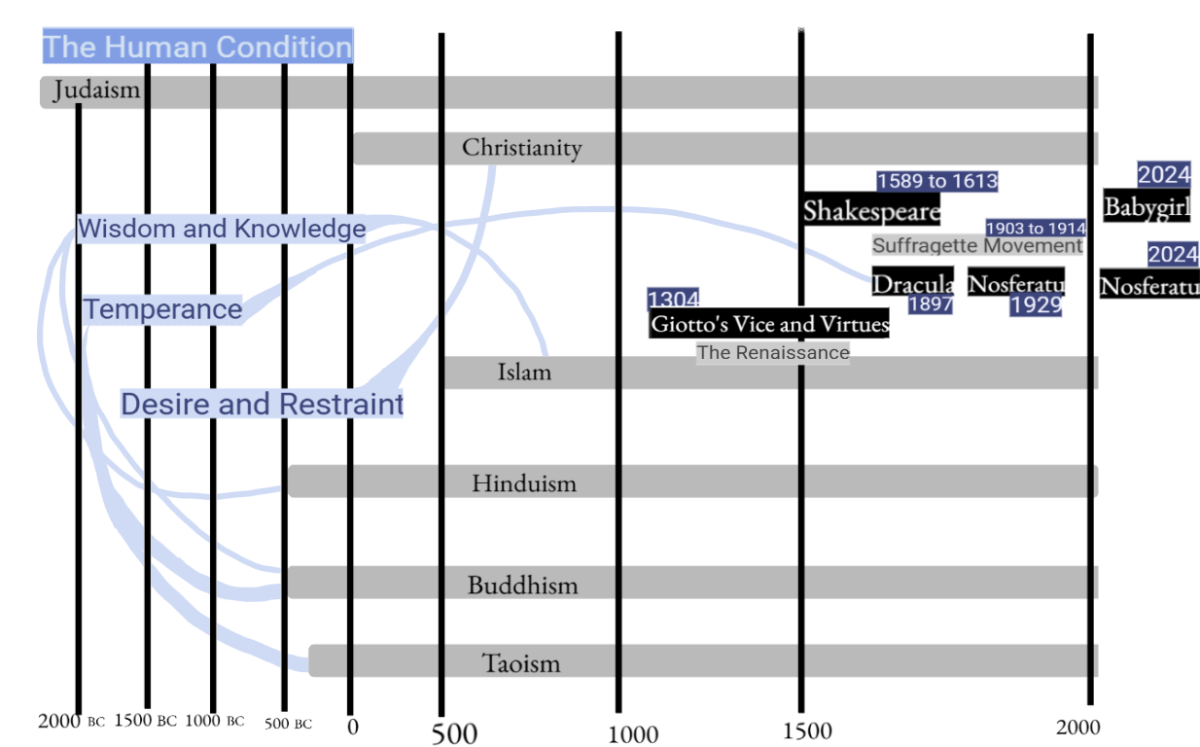

Art thrives on the tension between opposing forces: desire and restraint, justice and injustice, vice and virtue. From Giotto’s frescoes to the silver screen, stories like “Nosferatu” and “Babygirl” engage with these conflicts, offering critiques of societal norms and explorations of the human condition.

Giotto’s 14th-century chapel frescoes, a spatial and architectural medium, present the seven vices and virtues as allegorical figures. These panels, a distant ancestor to modern film, share a thematic lineage with Shakespearean drama and contemporary cinema. For example, Giotto’s “Inconstancy,” precariously balanced, mirrors Macbeth’s descent into chaos, both embodying the destructive nature of unchecked ambition.

This connection highlights how different mediums — painting, theatre and film — can explore similar thematic concerns and shared ideals.

The interplay of vice and virtue often hinges on the concept of desire and makes one wonder if desire is inherently destructive. Religious traditions, emphasizing virtues like chastity and wisdom, offer a moral framework for interpreting narratives as both cautionary and redemptive. These virtues such as prudence, temperance, fortitude and justice resonate across cultures and faiths.

Prudence, wisdom and knowledge are universal virtues that manifest differently across traditions. Hinduism’s viveka, discernment when translated to English, and the goddess Saraswati embody this ideal, while Buddhism’s prajna, wisdom, on the Eightfold Path emphasizes understanding reality. The Quran speaks of hikmah, wisdom as divine guidance. Giotto’s “Prudentia,” holding a mirror of self-knowledge, connects introspection to prudence and wisdom.

This resonates with the arcs of female protagonists facing societal constraints. Ophelia in “Hamlet,” and the heroines of “Nosferatu” and “Baby Girl,” grapple with inner desires versus external expectations. This pursuit of balance connects these characters across time and medium.

Temperance, self-control and balance find expression in Taoism’s harmony with the Tao, Islam’s taqwa, self-restraint, and Buddhism’s Middle Way. Giotto’s “Temperantia,” embodying measured action, parallels Prospero’s journey from vengeance to forgiveness in “The Tempest.” In “Babygirl,” the protagonist’s navigation of stigmatized female sexuality embodies this struggle for balance. Conversely, “Nosferatu’s” vampiric figures, driven by unrestrained desire, serve as a cautionary counterpoint, highlighting the dangers of unchecked impulses.

The specter of gynophobia, the fear of women, casts a long shadow across these narratives. Shakespeare’s “Othello” reflects this fear, as does the predatory Count Orlok in “Nosferatu,” who embodies societal anxieties surrounding female autonomy. This connects to the stigmatization faced by the protagonist in “Babygirl.” Giotto’s vices, like “Despair” and “Inconstancy,” further illuminate the double bind imposed on women.

This fear, whether rooted in classism or a broader anxiety surrounding female power, is a recurring motif across these works.

From Giotto’s frescoes to Shakespeare’s plays and modern cinema, cultural narratives evolve, repurposing ancient symbols to address contemporary issues. The vampiric nature of power, where one’s rise necessitates another’s fall, echoes across these mediums.

These stories, guided by universal religious values — humility, charity, forgiveness, prudence, fortitude, temperance and justice — compel us to reflect on our own moral struggles, reminding us that while the medium may change, the fundamental themes of the human experience remain eternal.