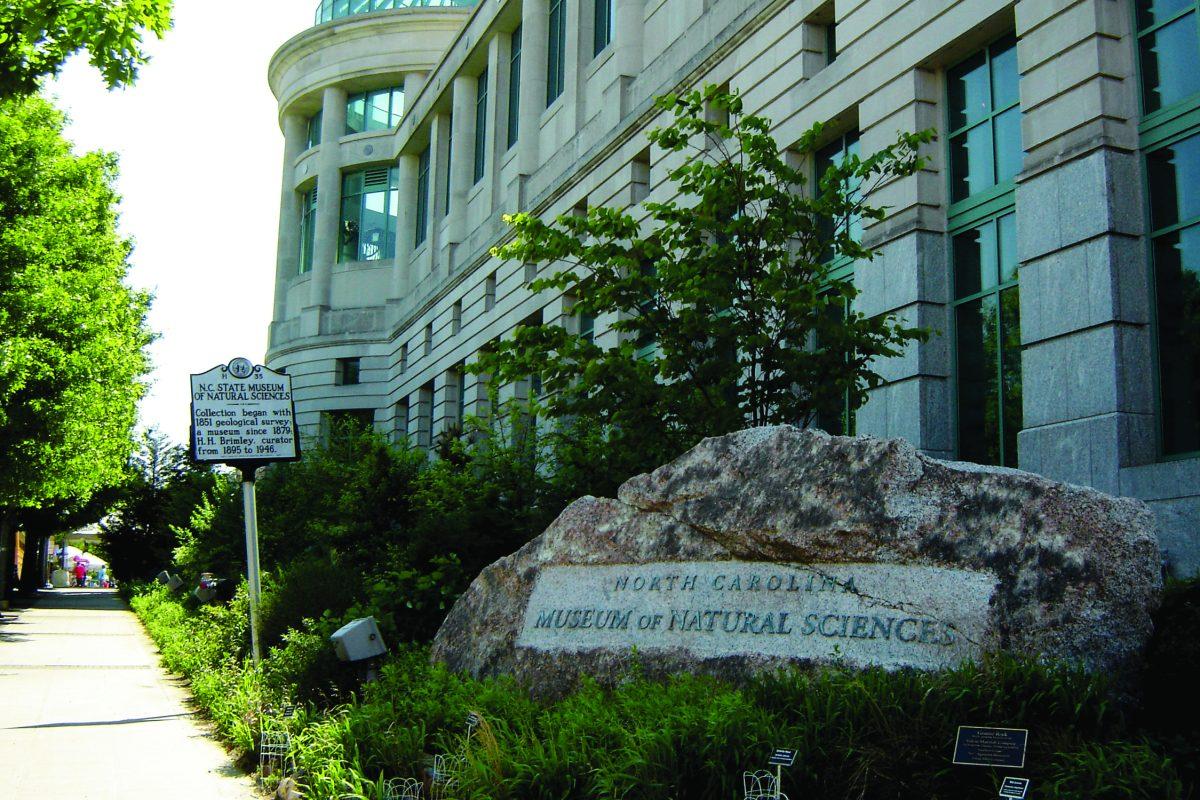

African American artists and educators gathered at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences for the 24th Annual African American Cultural Celebration to commemorate heritage, health, history and more.

Throughout the day, there were performances by drama groups, spoken word artists and storytellers. Intermixed between the museum’s dinosaur exhibits were presenters teaching about Black history, selling art and talking about local educational resources.

Belinda Alston was a presenter with the Heritage Quilters, a group of textile artists who create a diverse range of stitched works. The organization hosted tables with crafts and had many quilts on display in the first-floor lobby.

Alston said quilting has a historical significance to Black communities because of its origin. Typically, white families could buy new fabric and customize colors for their textiles, but this wasn’t always the case for Black families.

“You would take cloths and flour sacks and whatever materials that you had access to,” Alston said. “If you worked in the house where they gave you the scraps of the fabric that they didn’t want anymore, you took that. And you repurpose it for your family because that was a need.”

Somewhere along the line, the irregular, non-traditional quilting of Black communities became recognized as legitimate art and expression. The Heritage Quilters used both traditional techniques and unconstrained methods that were consistent with Black communities.

Members of the organization spoke to onlookers and helped children glue triangles of fabric to templates. Next to one of their quilts was another table hosting Alfreda Johnson, a sweetgrass weaver from South Carolina, showcasing another multi-generational art form that has roots in the unique African American experience.

The Heritage Quilters tables were popular with children and adults, both excited to take part in an art that might seem intimidating.

“This was a special opportunity, an honor, for us to be able to present quilting and to carry on the tradition,” Alston said.

Pinkie Strother is a multi-talented artist who was also presenting at the celebration. Her exhibit was meant to explore a historically significant piece of North Carolina Black history: Palmer Memorial Institute.

Palmer Memorial Institute was a prestigious college located in Sedalia, North Carolina, operational from 1902-1971. It was a preparatory school for Black students, where they could study specialties like ministry and nursing.

Strother had sculpted a miniature classroom full of Black students and a teacher moving throughout, powered by an electrical circuit she built. There were posters and images exploring the history and significance of the school.

“So many people came through here and never heard of the place,” Strother said. “That means that history, Black history, is not being taught.”

Strother said events like the Annual African American Cultural Celebration are important because it is one of the only places guaranteed to teach about authentic Black history.

A few floors up, tables were showcasing several specialized sects of the libraries of North Carolina. These included Accessible Books and Library Services, the Government and Heritage Library and the State Archives. There were quizzes about Black historical figures from North Carolina, displays of accessible library tools and a hands-on Wheel of History for kids to learn about specific events.

In another section of the museum was Willa Brigham, an artist, writer, storyteller and speaker who had a table with a range of her works, including CDs, textile arts and children’s books.

“As a speaker and storyteller, I have an opportunity to plant seeds of love, communication, connection, diversity, inclusiveness, equity, all in stories, songs and poems,” Brigham said.

Her art arose out of a love for reading, music and teaching in a way that children enjoyed. She found that her kids listened much better if she sang instead of scolded. She always made up stories instead of reading them from books. Above all, she found it essential to teach joyfully.

“The bottom line is, we are all on this great planet together,” Brigham said. “And it’s necessary to cooperate and move forward in a positive manner together.”

Across from Brigham’s table was a separate room, packed full of children. They crowded around a speaker from the North Carolina Association of Black Storytellers.

“A little girl came by, white as snow,” Brigham said as she gestured to the rack displaying her textile prints. “She picked the blackest [illustration] I’ve made. That’s the one she loved. She hasn’t been told any difference. It’s all taught, so why can’t we choose to teach love?”