This summer, NC State is set to break ground on a $140 million renovation project on Dabney Hall that is set to last through 2029. The renovation comes after years of complaints concerning Dabney’s conditions.

The occupied renovation of the building will work on floors in phases and will commence in the summer of 2025. The project will begin in June with the construction of swing space in Broughton Hall. While each floor of Dabney is renovated, faculty and research from the Department of Chemistry will be moved to Broughton.

The University has state legislature funding for two phases of construction: $60 million for general infrastructure amendments and renovation for the seventh and eighth floors, followed by an $80 million injection to work on floors three through six.

A third phase to round out the renovation, including changes to Cox Hall, will be contingent on further funding from the state. NC State spokesperson Mick Kulikowski said completing the renovation in its entirety is a high priority for the University and it plans to request additional funding for the project during the next state budget cycle.

Dabney was originally constructed in 1969. According to faculty in the chemistry department, the infrastructure and facilities of the building have not been up to standard for years.

“The current state of the facilities is terrible,” said Leslie Sombers, professor in the Department of Chemistry and university faculty scholar. “It’s ridiculously bad and embarrassing almost. I don’t want to bring people from other universities over. It’s not functional, and it just looks awful.”

A 2005 report conducted by a committee of external professionals from other universities said Dabney was “in extremely poor shape,” and stated there were “insoluble” problems with temperature control, AC failures, flooding, unbalanced air handling, chemical odors and an amount of fume hoods incompatible with modern standards.

A 2015 health and safety report from the Department of Chemistry cited 42 safety deficiencies from an annual inspection of fume hoods in the building. The report called these deficiencies “a constant feature of annual Dabney Hall inspections and points to what, to date, are intractable problems related to the design of the building.”

Air handling and HVAC issues have been a primary point of concern. Several large-scale renovations on the HVAC system have been conducted since the 1990s, but air condition issues have remained. A 2016 evaluation of the HVAC system from RMF Engineering highlighted dozens of issues within the building. Sombers said the air handling reports often “read like a horror novel.”

Jim Martin, professor in the department for over 30 years, used to have lab space situated on the eighth floor of Dabney. For years, Martin and his students reported questionable odors and recorded volatile organic chemical issues with air quality sensors in 2021.

Though the University dismissed concerns after conducting several air quality tests over the course of three years, Martin said he was relocated to Centennial Campus after a student reported becoming sick.

“Two years later, after spending $800,000, it was determined that the airflow in those labs would never be able to be balanced,” Martin said. “So for a year and a half now it’s been decided that I was going to be permanently in Partners III and my old labs in Dabney Hall had to be vacated … and those labs are not going to be occupied again until renovated.”

Martin’s former labs on the eighth floor will be one of the first areas addressed in the renovation project. A full HVAC overhaul was one of the initial prompts for funding the project. According to various construction managers in a town hall last month, the project will gut the building down to the structure floor by floor and also replace the mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems.

Reza Ghiladi, professor and director of graduate programs in the department, said mechanical and electrical issues amount to power outages several times a semester.

“We have a lot of sensitive instrumentation that isn’t on backup power because the building is ill-equipped for it,” Ghiladi said. “When power goes down, it could take hours to a couple of days to get back up running. Depending on the length of the interruption, it could be relatively minor — with the exception that it could burn out equipment — to relatively major and just destroy weeks or months of work.”

Inhabitants of the building also point to vibrations and noise permeation as being disruptive to research. Alena Joginant, a third-year PhD student in analytical chemistry, said these issues have been exacerbated by the construction of the Integrative Sciences Building next door.

“I would be graduated by the time that the actual renovation starts, but where I’m at in Cox we can hear the construction of the Integrated Science Building, and it’s not necessarily quiet, it is still disruptive,” Joignant said. “So I can only imagine what it would be like to be in the building during demo and renovation in the building that you’re in, whether it be the noise or vibration.”

Dabney and Cox are connected through a series of concrete balconies, and their floor plans are the result of a makeshift collaboration over the years. Joignant highlighted issues with the layout and structure of the buildings, citing the need for her to cross buildings to get to the nearest bathroom while working.

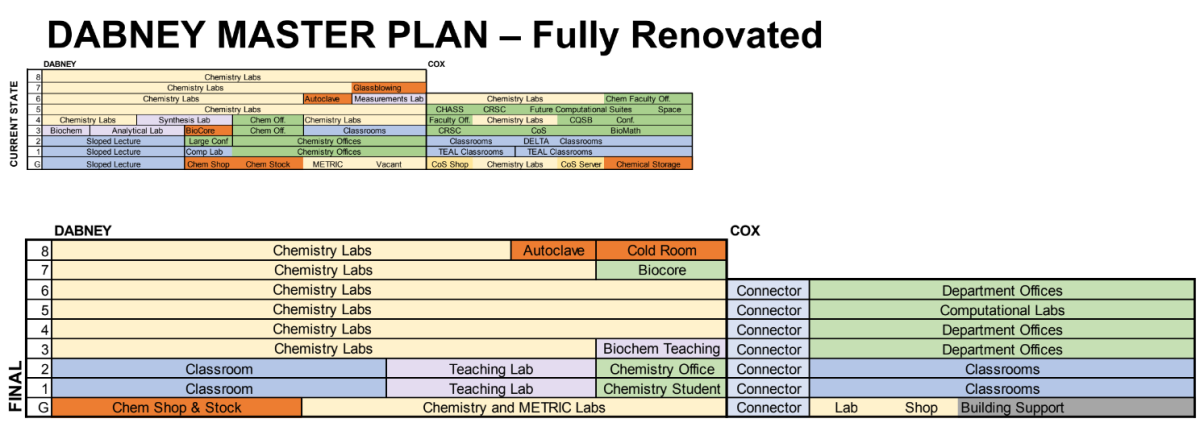

In the town hall last month, project managers from the architecture firm in charge of the project Lord Aeck Sargent outlined designs for Dabney and Cox. According to Lauren Rockart, principal-in-charge of the renovation, the primary intention of the renovation is to more effectively connect and integrate the two buildings.

This will include eliminating the balconies, creating more open floor concepts and conducting additional construction in between the two buildings to foster more seamless pathways for occupants. Whereas lab and office spaces are currently intertwined throughout both buildings, Rockart says the project plans to have all labs in Dabney and all offices in Cox by the end of the renovation.

Ghiladi and Martin said Dabney’s infrastructure is fundamentally unable to house the systems and facilities needed to make NC State a leader in chemistry research for the decades to come.

“Back in 1969, right, science wasn’t what it is today,” Martin said. “We didn’t understand what we needed to do in terms of a safety infrastructure. It’s a different world. So no, you never will be able to turn Dabney into a first-rate chemistry building.”

Ghiladi said Dabney was originally intended to accommodate more instruction than research, and the foundations of the building reflect this. He said the floor to ceiling height is inadequate, the aspect ratio is too square and the building is not designed to be energy efficient.

“But you’re still taking a building that should not be used for research and you’re trying to fit it into that sort of research regime,” Ghiladi said. “You’re basically holding back the department and the University from having a top chemistry program because you’re just putting lipstick on a pig essentially.”

Martin said he has been trying to get the University to replace Dabney since he came to the department in 1994.

“Chemistry is absolutely critical and central to a university like NC State, so why is it that NC State’s chemistry building is one of the worst in the entire 17 campus UNC system?” Martin said. “Why is it that you’ve got beautiful building after beautiful building built across Centennial Campus for engineering, the Plant Sciences Building and, you name it, and chemistry is the redheaded stepchild? … Dabney Hall, it’s not an architectural wonder. It should never, ever be a chemistry research building.”

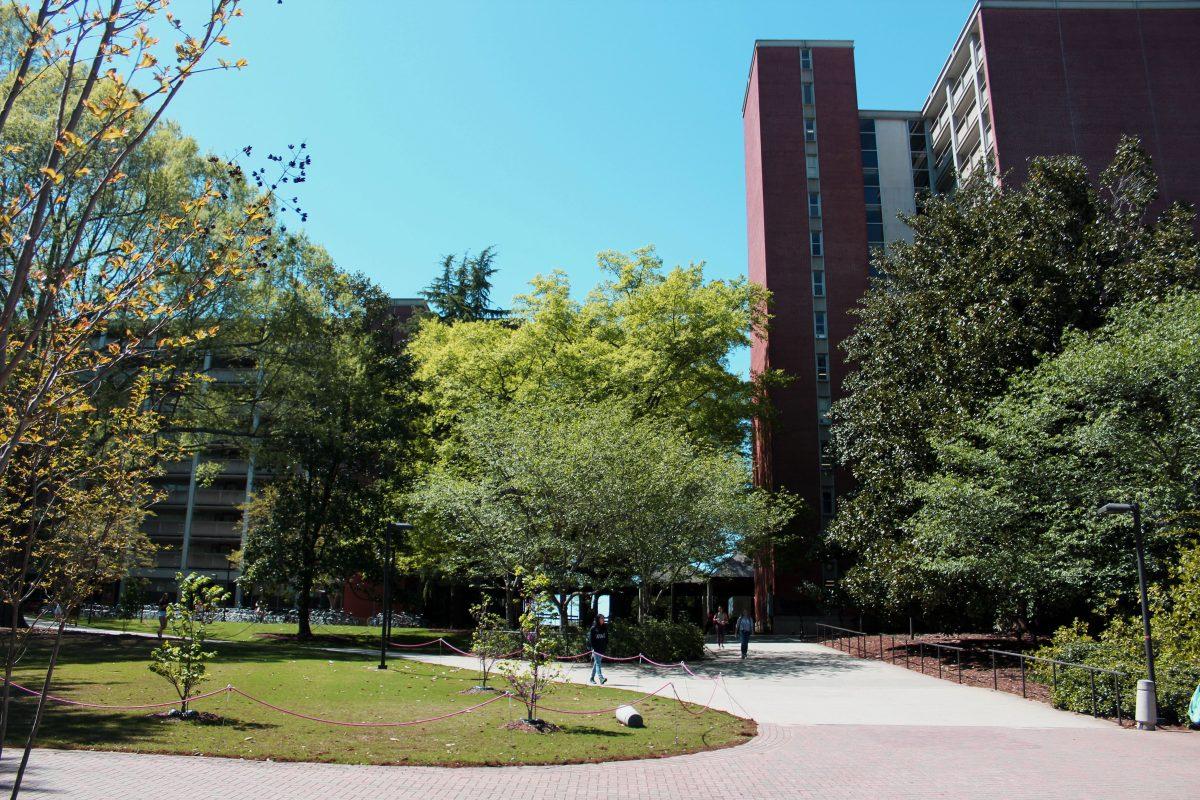

Dabney Hall, home to NC State's Department of Chemistry, situated between Harrelson and Williams Halls in 2010.