Following the deeply divisive era of apartheid in South Africa, the nation embarked on a groundbreaking and compassionate path toward healing and unity. In an unprecedented move, they established the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, aimed at reconciling with their white neighbors and addressing the injustices of the past.

The TRC was characterized by two distinctive features: First, it undertook an examination of war crimes and human rights abuses committed by all parties, including those done by Black anti-apartheid activists. Second, the commission adopted principles of restorative justice, facilitating direct encounters between offenders and victims to uncover the truth. Offenders who sincerely admitted to their involvement in relatively minor crimes were eligible for amnesty.

This approach differs immensely from the retributive justice model employed by the former World War II allies against Holocaust offenders during the Nuremberg trials. In the Nuremberg trials, high offenders were sentenced to death or life imprisonment to deter future offenders.

In contrast to retributive justice models, what distinguishes restorative justice is its focus on healing and providing resolution for the victims and their relatives. This approach seeks to clarify what happened to the victim and facilitate a cathartic moment to improve victims’ lives over punishing the offenders.

During my research for this article, I experienced profound emotional responses while observing the trials. I was deeply moved, almost to the point of tears and felt chills during the shocking testimonies that described barbaric acts of violence, ranging from genital mutilation to amputation.

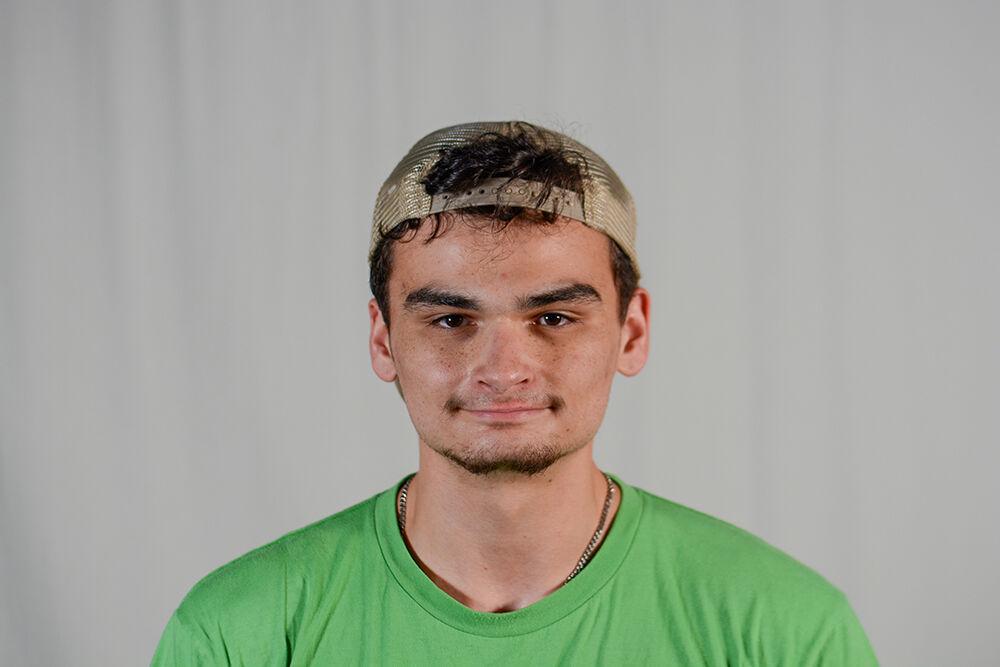

Not only did these poignant moments contribute to the healing of individual victims, but they also played a significant role in the broader healing of the nation. Timothy Hinton, an NC State professor of philosophy and a white South African anti-apartheid activist, highlighted the testimony concerning the death of Matthew Goniwe as one such impactful instance. Goniwe was a member of the Cradock Four, an anti-apartheid group that became idolized through their death.

“[Goniwe] was an activist from the Eastern Cape, and I remember vividly when he disappeared,” Hinton said. “I think that [the testimony] was very transformative because you had to pretend that it wasn’t so bad. But by looking at this graphic testimony of what they do — they were continuing to have what you would call a barbecue, the cops, while he was dying. … It was the most hideous kind of callous disregard of his humanity. So, I think that moments like that were very transformative for the people who were open to being transformed.”

Unfortunately, the success of the TRC program is debatable, especially when you consider the data. Out of 7,112 amnesty applications, only 849 were granted.

Hinton slightly hints at why the TRC’s success is often considered limited. The absence of sincerity, he said, was a key factor in the TRC’s limited success as it hindered the full potential for national healing and reconciliation.

“I think success would require a certain willingness on the part of most people in the country to take the process seriously,” Hinton said. “There’s the … moral or a spiritual question like how, as a society, do we confront the evils of the past?”

Despite only being partially successful, the TRC offers a valuable blueprint for implementing restorative justice more effectively. It suggests that for restorative justice to be more effective, it requires comprehensive participation, absolute transparency and a collective commitment to addressing past wrongs.

Applying these principles in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States could have facilitated crucial conversations, fostering reconciliation among various ethnic groups. By acknowledging injustices and facilitating dialogue, a similar commission could have bridged divides and initiated healing much earlier in American history.

Our nation is beginning to recognize and amend its previous missteps by increasingly incorporating restorative justice techniques into the legal system, though only gradually.

Our country’s drug courts are integrating aspects of restorative justice in a way that ultimately benefits the individual facing substance abuse issues. In these courts, the concept of punishment is reframed to support the rehabilitation of the drug user. Their sentences usually include providing access to substance abuse treatment programs. Additionally, these courts enforce retributive measures through accountability. Offenders are regularly drug tested, and other minute punitive measures are taken to encourage compliance with treatment and recovery.

Unfortunately, the integration of mixed models of retributive and restorative justice remains uncommon in our country, with there only being 4,000 drug courts across the United States. It is not too late. Implementing methods inspired by the TRC into the current justice system, especially where minority groups are disproportionately affected, will lead to significant positive changes. By adopting restorative justice principles, the U.S. can address systemic biases and reduce mass incarceration to promote a more equitable society.