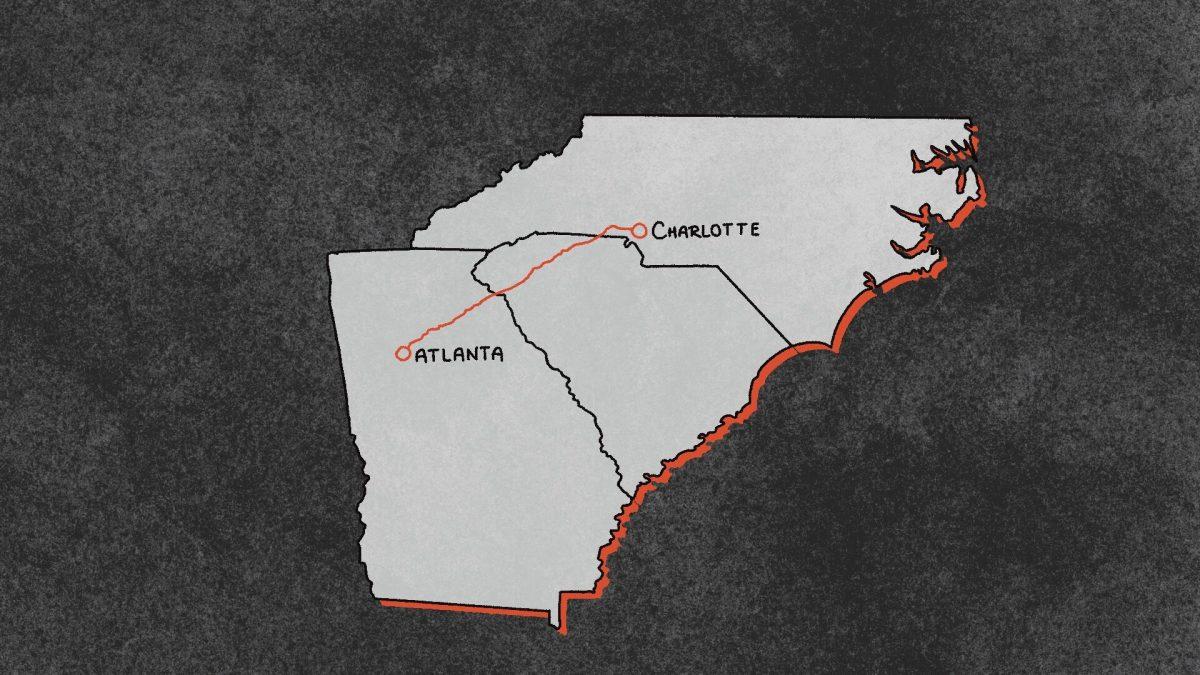

The Office of University Interdisciplinary Programs hosted an event in Hunt Library on Nov. 13 titled “Envisioning Urban Futures: Charlanta,” a presentation and demonstration-focused exploration into urban planning of a projected megapolis extending along Interstate 85, from Charlotte, North Carolina to Atlanta, Georgia.

In the auditorium were several speakers and presenters, including Raleigh mayoral-elect Janet Cowell, Dara Bloom, Francis de los Reyes, Liz McCormick, Dan Burden and Adam Terando.

Terando, the lead author and an adjunct professor with the Applied Ecology Department, initially described the potential megapolis in a 2014 paper titled “The Southern Megapolis: Using the past to predict the future of urban sprawl in the Southeast U.S.”

“What is the future of humanity?” Terrando said. “I’m really going to talk about this in terms of Charlanta. What type of cities do we want for a 10 billion person Earth?”

Prior to the TED-style talks, the band Red Nucleus played music in the auditorium, where several groups, organizations and people presented their ideas relating to the future of urban planning.

At a nearby table sat Roger Magarey, a senior researcher at the Center for Integrated Pest Management, and his son Sam, a middle school student, who shared their ideas of a new neighborhood design that emphasizes safety and walkability. The need for redesigned neighborhoods, Magarey said, comes from a near fatal encounter experienced on Hillsborough Street.

“We’re going to take the house, we’re going to turn it around so that the garage and the driveway are in the back of the house and connect to the road,” Magarey said. “When you go out the front of the house, there’s this nice green space and the kids can play together.”

AI-generated images displayed on a TV of the neighborhoods, designed by the fractal patterns found in the veins of a leaf or the air sacs in lungs, with text that read, “Can we get back to the idea of a village?”

“I was almost killed by a car when walking down Hillsborough at night,” Margarey said. “The sky was dark and a guy drove a million miles an hour into a parking lot and almost cleaned me up. That sowed the seed that separates cars and people, and then I came up with this design about four or five years ago. … I thought this is a great opportunity to get my son involved and actually take her from a crude drawing on a piece of paper to this graphical design.”

Magarey, who is originally from Australia, thinks that for a country as developed as America, there are many issues regarding the country’s transit.

“I see America as an advanced country, but we have a lot of problems where technology, such as the car, has created its own problems and now needs a solution,” Margarey said.

Across the room, on the wall was a quote from former chairman and CEO of Bank of America, Hugh L. McColl Jr., reading: “Brainpower doesn’t only come in blue pinstripe suits.” Directly underneath the quote sat a board game titled “FutureScape,” designed by an interdisciplinary team of coastal resilience and geospatial scientists, coastal planning specialists, storytelling and engagement experts.

Lexi Boudreau, a second-year studying applied mathematics and industrial engineering, presented the game. She works as a research assistant for the Center for Geospatial Analytics.

“The goal of the game is for people to have conversations so that it’s like gamification of a real situation,” Bourreau said. “It’s about talking about what our values are, our greater plan, in a more relaxed environment. Do we want to resist climate change or do we want to accept it?”

Three sophomores at Wake Stem Early College High School, Garrett Frasure, Youssef Aboutikab and Patit Saha, were tasked with researching data in the Charlanta region with a focus on housing concerns, economic opportunities and disparities, predominantly amongst Black and Hispanic communities.

“Redlining is a discriminatory practice of denying people mortgage loans or insurance loans based on their ethnic background,” Aboutikab said. “Even though the practice was outlawed through the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the problem persists. We found low-income areas weren’t as highly affected by flood zones as low-income areas that had a Hispanic population. We were wondering, well, why is this so? Looking into it, we found redlining has a major effect.”

Saha explained some of the ways to effectively respond to such discriminatory practices, placing an emphasis on community building.

“We want to work closely with the community on itself to grow its own needs so it doesn’t need people in industries to move in and colonize the region,” Saha said. “Instead, we want to work with professionals in the region to create jobs that are appealing to the people living in the county. We can approve this by using the government and levers of power by voting for legislators who would want to work on plans, redevelop plans and provide funding for these communities to increase economic opportunities.”

At the end of the auditorium presentations, audience members passed around a microphone to ask the speakers questions. The last question was asked by Andre Taybron, a contract negotiator with NC State’s Research Administration and Compliance division.

“Have you had the opportunity to work in a predominantly Black or historically Black community, and if so, what were some of the successes and some of the challenges that you can bring to this conversation,” Taybron said.

A few seconds of silence ensued until Dan Burden responded. Burden is the director of Inspiration and Innovation for Blue Zones and a world renowned civic innovator. In the late 1990s, he helped redesign Hillsborough Street to be safer, after being a street responsible for claiming more lives than any other street in N.C., Burden said.

“Parkland-Spanaway in Tacoma is a neighborhood that got overlooked forever and it has the highest fatality count and security issues,” Burden said. “Our challenge in that neighborhood is getting people to regain hope. They’ve lost hope. Everything was done against them, and we have to invent new techniques to reach out to people, meet them, one-on-one and regain some footing for them. I’ve worked in all Hispanic communities. I’ve worked in Black communities. The process is similar. It’s just that you have to work harder when folks gave up on the fact that anyone is going to help them.”

On their way out, Taybron clarified their reasoning in asking the question.

“I didn’t see but maybe one or two people that looked like me in the presentation,” Taybron said. “Historically, communities of color have been left out of the conversation, or they may surface later in the process instead of early on, and maybe not throughout the full process. Even if they are part of the process, funding plays a part in who can make decisions. I recommend there is just more mindfulness and awareness when speaking or approaching communities either left out or maybe on the fringe for developments.”