When people think of animatronics, they likely picture the creepy band from Chuck E. Cheese or the infamous horror video game Five Nights at Freddy’s. However, many NC State students may not know that animatronics were a part of the university in 1946 with the creation of “Hell,” a robotic mascot towering over seven feet tall.

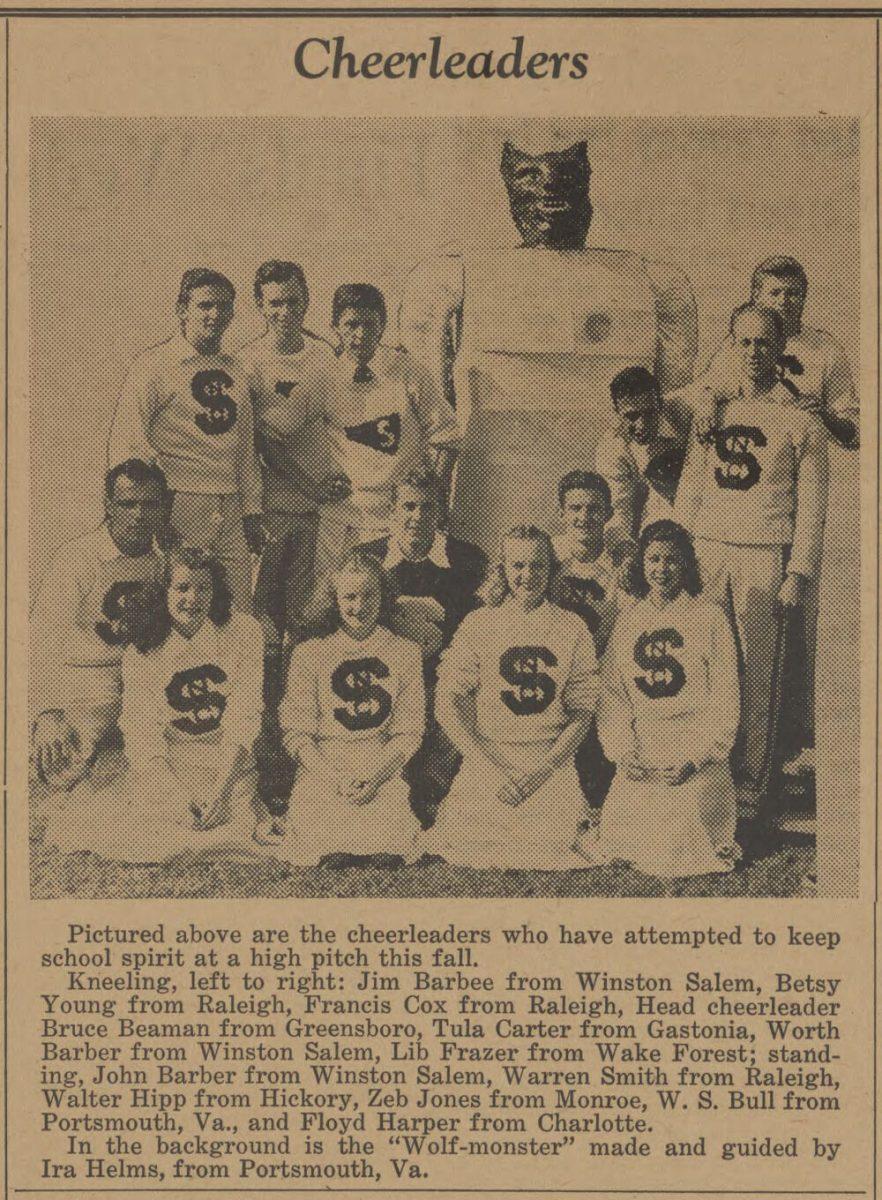

The NC State mascot has undergone many changes since the school first adopted the title in the early 1920s, but the uncanny robot took intimidating opponents to a new level. Hell — also referred to as “Wolf-monster” — was created in 1946 by Ira Helms, a mechanical engineering student and instructor in the Mechanical Drawing Department.

Special Collections librarian Taylor Wolford said before the establishment of the Wolfpack, students introduced a variety of mascots to campus.

“Before we even were a Wolfpack, we had whatever mascots the students could devise to demonstrate their school spirit,” Wolford said. “Some examples include the 5-year-old son of former NC State President Wallace Carl Riddick and a pair of bulldogs named Togo and Tige.”

Helms brought Hell to life amid post-World War II excitement for NC State. Tim Peeler, a writer and editor for University Communications and Marketing, said the student population jumped from about 500 during the war to around 5,100 in 1946.

Peeler said during this time campus bustled with increased activity and the university revitalized its athletics reputation, hiring coaches and growing its teams.

Under head coach Beattie Feathers, the football team qualified for a bowl game in 1946 after not having won a conference championship for nearly 20 years.

“Those times in the aftermath of World War II were some of the most electric ever,” Peeler said.

Helms constructed his mechanical wolf entirely from scratch and made plans to showcase his creation at a football game against Wake Forest, in the wake of the rise in school spirit on campus. The name was supposedly a shortened version of its creator’s surname.

Wolford said Helms ran out of time to finalize the mechanics of the mascot and resorted to standing inside the structure to move it manually. Another student followed closely behind with a fake control device to maintain the facade of a fully mechanized robot.

Faking Hell’s autonomy came with challenges at times, such as when Helms decided to touch up the robot with spray paint on the way to a game in Jacksonville.

“[Helms] was kind of overwhelmed by the fumes of the paint when he got in there and had to take the costume off,” Peeler said.

Hell made regular appearances at football games during the 1946 season, but was retired only a year later.

The exact cause of death remains somewhat of a mystery, but Wolford said she guesses it may have been a result of faulty mechanics.

“It was supposed to be able to operate on its own, and maybe after wearing it over time, it started to lose some of its mobility,” Wolford said.

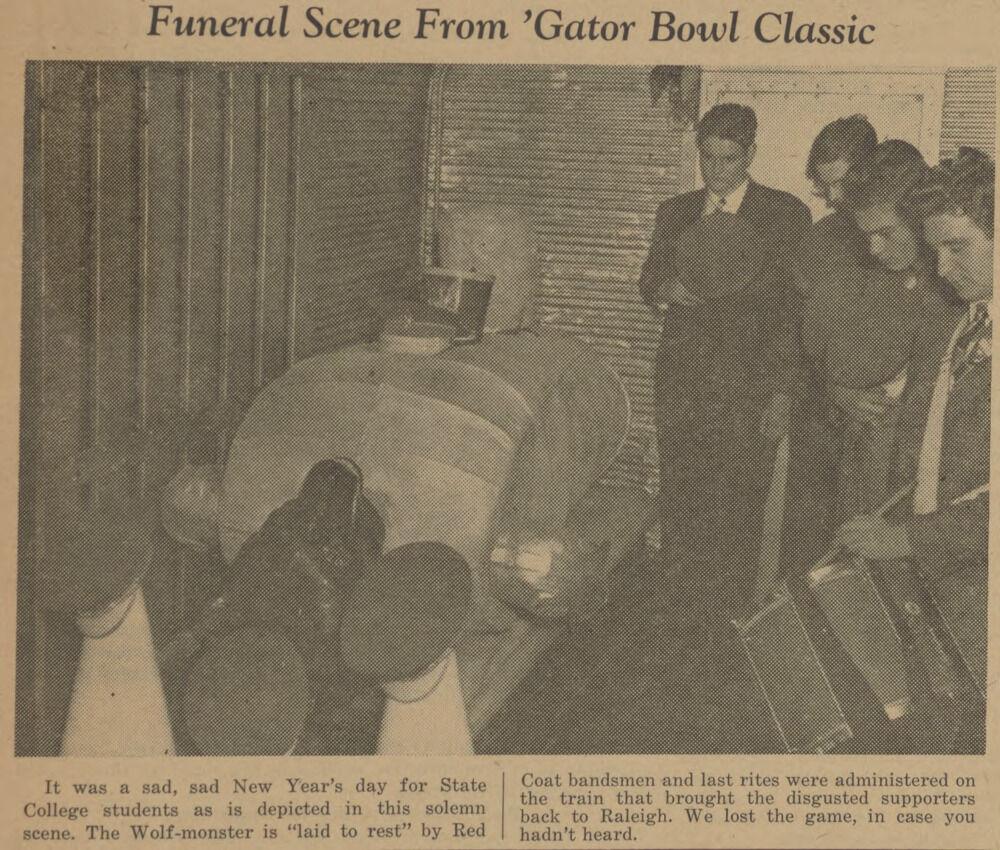

In a train car bringing NC State fans back to Raleigh from the 1947 Gator Bowl, the Red Coat Bandsmen paid their respects in a formal funeral for the Wolf-monster. A somber photo of the service was featured on the front cover of The Technician along with a snarky comment about losing the game to the Oklahoma Sooners.

“I think that really invokes that kind of community, but also silly and irreverent aspect of NC State’s history,” Wolford said.

Since the Wolf-monster’s fifteen minutes of fame, NC State has yet to see another rendition of a robotic mascot. The closest attempt was made 50 years later by a group of students who created a robotic model of the iconic NC State Memorial Belltower.

“There was a belltower that students put together in the early 2000s … and it was kind of a robotics-automated kind of thing,” Peeler said.

While Hell may have been unconventional, its story offers a glimpse into NC State Pride. The University has a history of demonstrating school spirit, from live mascots to the beloved Mr. and Mrs. Wuf we know today.

“It just is one of those experiential branding opportunities that the university has cultivated through the years to say, ‘This is who we are and what we are,’” Peeler said.