April is Arab American Heritage Month featuring a HistTalk event to educate the NC State community on Arab history.

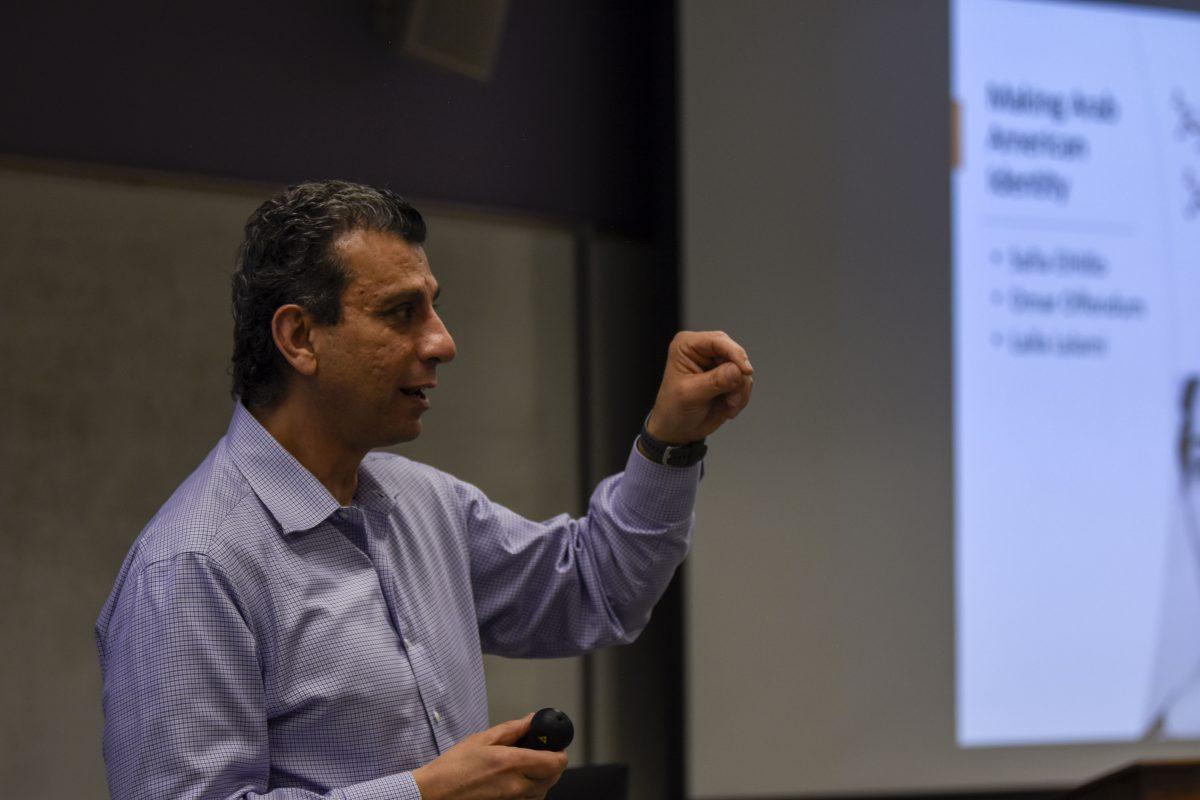

The event began with exploring the definition of Arab, a group that seems white on paper, but is not in reality. Akram Khater, the event’s speaker and director of NC State’s Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora studies, expanded on this definition.

“To be Arab in America is to be in a liminal state — to belong and not belong, to be accepted and not accepted, to be racialized legally as white and to be racialized in practice as non-white,” Khater said.

The U.S. considers Arabs white on census forms and any documentation that requires a race or ethnicity to be filled out. The origin of this categorization goes back to the case of Dow v. United States, where a Syrian defendant was fighting for U.S. citizenship on the basis of being white, a socially beneficial distinction then and now.

“It’s really kind of funny actually,” Khater said. “They argued, ‘If Christ is white and we’re Christian, we’re the original Christian. Therefore, we are white.’ And the two people arguing the case in South Carolina were two Jewish lawyers from New York because they were worried that if Arabs are going to be considered not eligible for citizenship, the Jewish community is going to be next.”

They won, and ever since those who would fall under Middle Eastern or northern African categorization have been deemed white in official documentation.

Even within the community there is confusion and tension surrounding what it means to be Arab and who that includes. “Arab” covers a vast geographic area from Arabic speaking countries in the Middle East, like Lebanon, to northern African countries like Egypt. In a geographic area that large, the culture is not homogenous throughout.

“Within the community, they are trying to figure out who they are as well,” Khater said. “Are they Lebanese? Are they Arab? Are they Syrian? It’s not straightforward. It’s not like it was a prepackaged identity.”

Ultimately, one of Khater’s goals is to reinsert Arabs into American history, where they have been historically erased apart from violent events.

“You can open textbooks, college and undergraduate, K-12 textbooks about the history of America,” Khater said. “[Arabs] are nowhere to be seen, and wherever we emerge, we emerge in relationship with some sort of violent act. Our story, whatever it’s called, is highly skewed and more often than not we’re not allowed to tell it.”

Khater, born and raised in Lebanon, broke down some of the biggest immigration myths.

“Part of the myth of immigrating to the United States is that people came escaping persecution and they want to stay [in the U.S.],” Khater said. “This idea that somehow immigrants come and completely abandon who they are is nonsense. Rather, they try to build a sense of community, maintain a sense of identity and in the process create some sort of hybrid.”

Savannah Wade, student services coordinator for the Department of History, said the goal is to have two HistTalk lectures per semester and have them line up with the heritage months happening.

“I think the most important part of HistTalks is people outside of history being able to engage with history, being able to be introduced to marginalized communities, to be introduced to perspectives that they’re not used to being introduced to,” Wade said. “I think doing it through the lens of history is what makes it so valid and important.”

HistTalks allow professors to bring content they would normally only talk about in a classroom setting to the public and educate the community on important topics outside of graded coursework.

“[The history department] wants to be engaged with the world as it is,” Wade said. “We want to bring history to the forefront of being part of the conversations about marginalized communities, being part of the conversations about public history and its involvement in museums. These conversations that people are not sure how to have, we want to facilitate them.”