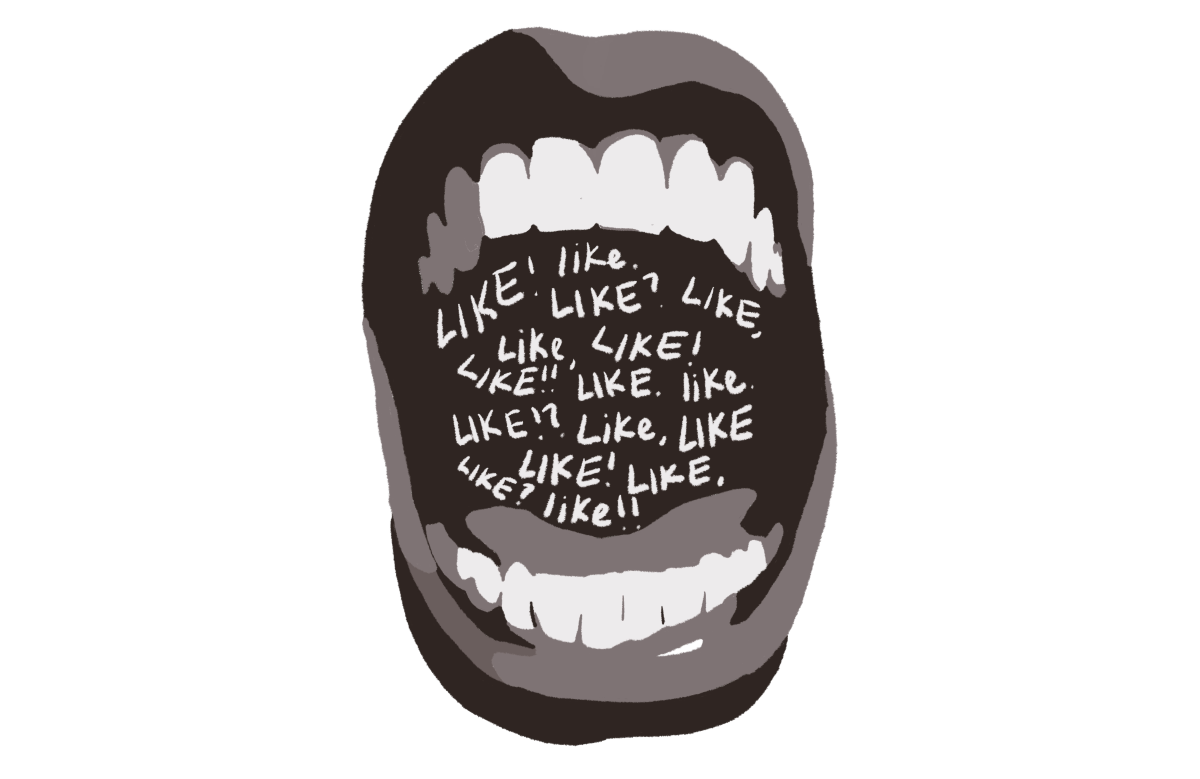

For most of my life, I’ve been told to stop using the word “like,” as it may make me sound less confident or educated in daily conversations. In fact, there’s quite a bit of online discussion about the use of the word and how people will benefit from not saying it. Even WikiHow has a “How to Stop Saying the Word ‘Like’” page. However, I think it’s time we look back at how this word has historically been used by all, not just by young women — contrary to popular belief.

I spoke with Robin Dodsworth, professor of linguistics, about the use of the word “like” and how it has changed over time.

“The word ‘like’ has actually been evolving for several hundred years, even as much as 800 years,” Dodsworth said. “Early on it was a verb, and later on it started to acquire other syntactic functions including preposition. There is now an adverbial use, there’s a discourse marker used in a discourse, particle use, but those different syntactic functions have evolved at different times over the course of the last several hundred years.”

I also asked Dodsworth if she knew why the word has garnered such hatred or disdain in recent history. She noted that one of the reasons she thinks it’s been criticized is because it’s such a syntactically flexible word. It’s incredibly multifunctional, so why should we not all use “like” more? Dodsworth also referenced the newest use of the word is called quotative like, which refers to saying something, like — no pun intended — “They were like, ‘Hey, how are you?’”

This quotative like may have originated from the West Coast, which may have caused an association to certain people, such as valley girls, who have often received the short end of the stick in media representation and in general. Dodsworth said this connection is what also caused “like” to have criticism, despite it being widely used in other cases everywhere else throughout history. She also said that the other syntactic uses of “like” did not originate from the West Coast and have nothing to do with the valley girls.

Dodsworth also talked about the criticism that the high-rising terminal, or better known as “uptalk,” receives. Uptalk is essentially when a clause ends on a high inflection point, like a question. Similar to how “like” is criticized, uptalk is often associated with the valley girl persona and is seen as less professional or as a lack of confidence.

“There came to be an association between saying ‘be like,’ and the valley girl persona or other kinds of people they didn’t take very seriously,” Dodsworth said. “What happens is people tend to be ready all the time to criticize the way that young females talk. Anytime there’s some new thing in language or something that people think is new, they just kind of go ahead and associate it with young females. And why that is? We don’t know. But, we think it has something to do with people’s willingness to criticize young females in general.”

Criticizing the way young women speak is not unheard of at all. It’s important to acknowledge the age-old argument about who talks more: men or women. I’m sure many will recognize the redundant claim that women speak 20,000 words a day and men speak a mere 7,000. Claudia Hammond from BBC noted that this stereotype has no basis in scientific evidence. In some of the studies she referenced, where men’s and women’s communication had been analyzed, there’ve been differences, but they’ve been negligible.

However, in a study from 2020, researchers sat in college classrooms to see who talked more: men or women. The findings confirmed that male students talked 1.6 times more often than female students, and they often speak without raising their hands, interrupting the class and engaging in more prolonged conversation than their female counterparts.

Women were also found to have a less assertive tone than men when answering questions, which leads me to consider the fact that women may feel less inclined to speak in a room where men take up more of the vocal space and ask the questions first. This is seen in work settings as well, as noted by Elizabeth Weingarten from Behavioral Scientist.

The way women, especially young women, speak and answer questions has been scrutinized without any scientific or linguistic evidence. Using the word “like” often is not something that only young women practice, and it’s certainly not something that should continue to be critiqued or seen as lesser than. In fact, this incredible change of language and multifaceted uses of “like” should be celebrated, as language is constantly evolving and linguists are studying this on a day-to-day basis.

“If we transcend popular ideology, there’s absolutely no sense in which using the word ‘like’ a lot means that you are not confident or not educated or something like that,” Dodsworth said. “It’s simply a word that has taken on many different syntactic functions.”

So, just remember that using “like” in your daily conversations is more than OK; the word has way more historical significance than others might understand. “Like” is multifaceted, and if someone criticizes your use of it, pay them no mind at all.