Many students take exams and turn in assignments through platforms such as Cengage, Pearson and McGraw Hill, which sometimes come at a cost.

Kate Sappenfield, a second-year studying business administration, said her course materials this semester were costly.

“I had to pay around $500 this semester,” Sappenfield said. “A lot of it was online connect materials where you had to buy the textbook and the platform. I think that’s too expensive.”

Kaushya Bhattu, a second-year studying chemistry, said she bought unlimited Webassign access for $120 when she started college and bought a physics textbook for $90 this semester. Still, high costs remain a concern.

“All of the homework is on the online platform, so we don’t have an option but to pay for it,” Bhattu said.

However, some students must also pay for plain text documents, including Youssef Kozman, a second-year studying chemistry.

“My textiles in-class labs, which are just a couple of documents that could have been uploaded to Moodle, were $15,” Kozman said. “When there are documents that can be easily uploaded without a rights issue, there is no reason for us to be made to buy it, I think.”

Kozman said he had to pay $125 to use Cengage unlimited for one semester and still had to pay an extra $90 for a Webassign access to his physics class, despite the fact that Webassign is owned by Cengage.

“I am completely opposed to the idea of paying more than that Cengage unlimited subscription,” Kozman said. “It is already very expensive. To have a class that, for some reason, is just not included in it even though it uses the same website, to me makes no sense.”

This is also a challenge for the library, which traditionally helps students pay less for materials by lending them physical textbooks. David Tully works to address this as a librarian for student success and affordability.

“If an instructor requires students to purchase a digital access code as part of their course materials, then the library isn’t able to provide alternate support,” Tully said.

That’s one of the reasons the library launched the Alt-Textbook Project almost 10 years ago. The library cooperates with faculty members so that they can develop their own digital materials and make them available to students free of charge.

Tully said the program also gives faculty members greater control over the learning content for their class.

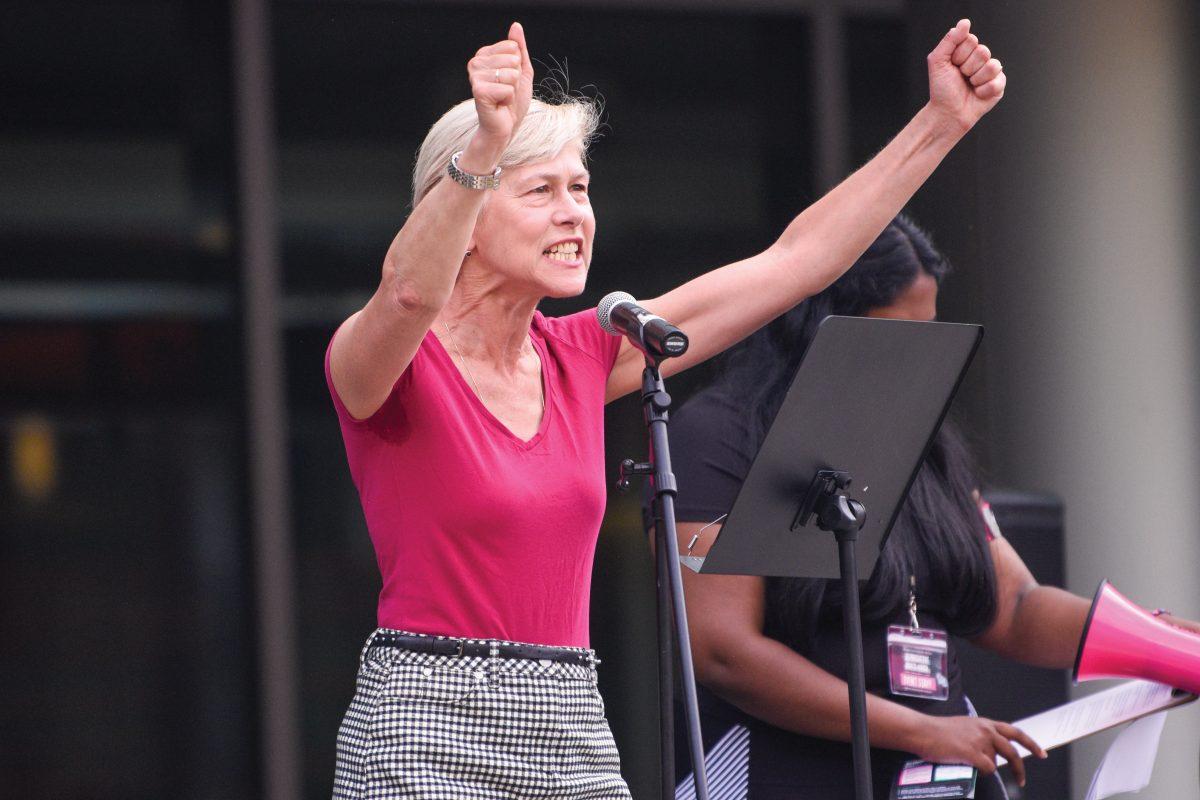

Cassie Lilly, an associate teaching professor of chemistry, is working on making the materials for her course available through the Alt-Textbook Project beginning in spring 2024.

“I wanted to make sure that the textbook for this course is accessible to my students at no cost,” Lilly said. “Another advantage is that I have the ability to manually change the content of the textbook, so I have it in my own hands.”

Tully said last year, over 3,600 students were enrolled in a course where the materials were free of charge thanks to the Alt-Textbook Project. Tully said the program has saved students $11.7 million.

Tully said the three main reasons there are not more courses with free materials are the limited time of faculty members, the limitations of copyright law and the lack of awareness about the program.

Kevin Oliver, department head of Teacher Education and Learning Sciences, said he isn’t aware of alternatives to paid online platforms, but they’re a useful learning method because they can be interactive.

“Quality distance education shouldn’t be independent reading online,” Oliver said.

Tully said he is optimistic the program will help more students reduce their total expenses in the future and more courses were converted to the Alt-Textbook Program last year than in any previous year.

More information about the Alt-Textbook Project can be found on the library’s website.