In literature and film classes, we learn that books and movies frequently follow a formula. It seems like every detail must have a meaning, whether it’s the color of Gatsby’s eyes, or the way Sofia Coppola directed her latest film.

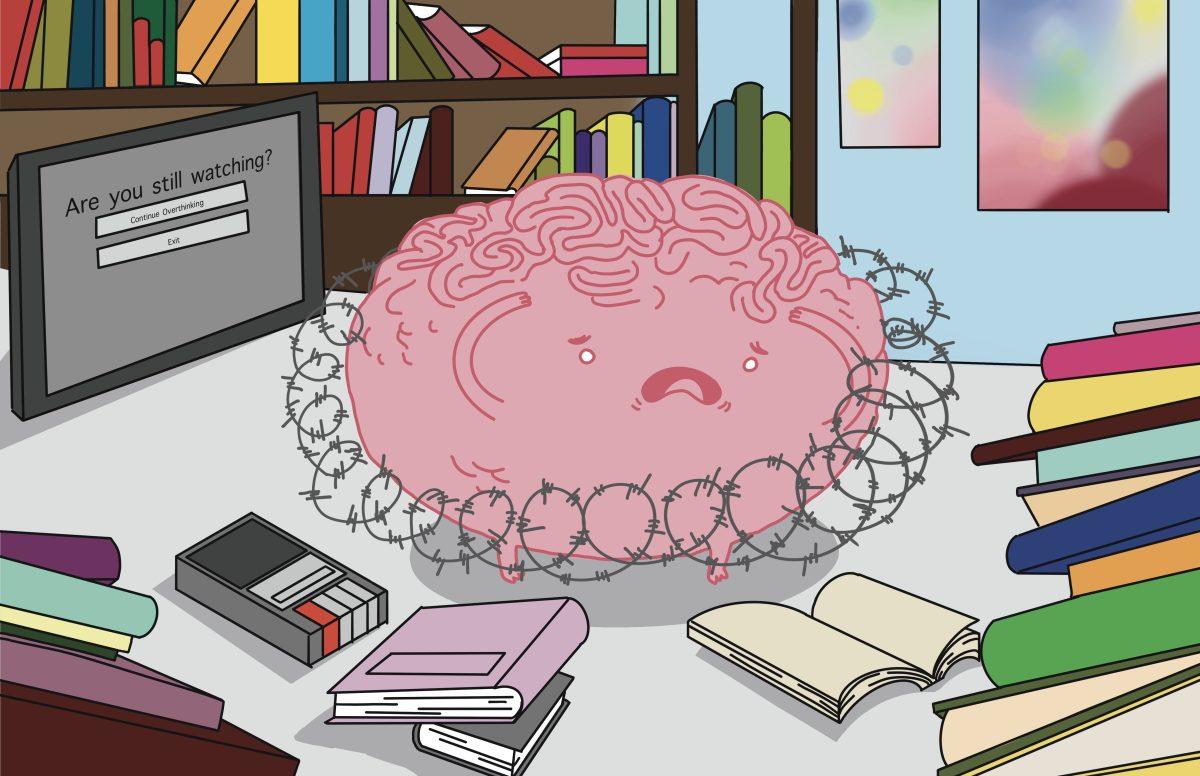

In certain contexts, intellectual speech makes sense but placing public media and content on such a high level makes it inaccessible to many people. Media, critical text and literature focus on bringing people together and diversifying the world, but it’s reaching a point where over-intellectualization is doing the opposite.

Theory is meant for the classroom and should not be pushed onto people who are just trying to have fun. Someone may want to watch something for entertainment, or even the pure aesthetics of it, and that shouldn’t be a problem.

Andrew Johnston, an associate professor of film studies in the Ph.D. program at NC State, focuses on film theory and animation studies. His classes are oriented around special topics such as film aesthetics, history of technologies in film and future classical methods.

“I think that often the word aesthetics becomes really loaded,” Johnston said. “It’s something that people think it’s got to be a serious image or something that has kind of like, a weight behind it, and it’s got some sort of importance associated with it. I don’t approach things in that way.”

One can’t help but ask the question, can I watch something purely for enjoyment, without the extra baggage attached?

NC State’s Bad Film Club goes against the grain of what you would expect a film club to cover. They screen objectively bad films, finding entertainment and community through movies that almost everyone would deem terrible.

Kevelle Wilson, a third-year studying business administration and Student Media employee, shares his thoughts on popular films and critical thinking when it comes to media.

“It’s just a unique perspective [that is important in a film], like I don’t want to see another movie that feels like a bunch of other movies,” Wilson said. “People should just enjoy movies for the reasons they enjoy them and don’t bash other people for that.”

Communities and critiques often participate in gatekeeping culture, leading to an in-group mentality that creates camaraderie between those with the same niche interests.

“Everybody gets caught up in hype, and sometimes it’s just fun to get caught up in the hype of something. People just want to be in a conversation about something,” Johnston said. “Not just because they want to see it, but because they want to talk to their friends about it.”

Johnston is less interested in critique culture and is more curious to know why someone decides to associate themselves with a certain form or genre of media.

“I am really interested in pleasure, right? Like: what people like when they’re watching something, whether it’s an animation or a film or video game, why they like it, and that often doesn’t become associated with a meaning that they’re deriving from it,” Johnston said. “What if we just looked at the immediate experience of doing something like how it makes us cry or laugh, or whatever, right?”

Idolization plays a big role in why people consume certain forms of media.

“Why do you go to movies you go to?,” Johnston said. “Producers are asking this all the time and it’s usually for one of two reasons. The first reason is stars. There’s a name attached with a particular production. And you’re familiar with that name and what they do. The second is genre right? The type of film that you enjoy.”

Although there is frequently an intended meaning behind a lot of details in the things we read and watch, it doesn’t mean they have to be over analyzed at every given moment we consume these things. We have the ability to enjoy art, without overintellectualizing it — and that may be the most freeing, therapeutic way to do so.