On Thursday the Federal Communications Commission approved one of the most intrusive and expansive regulations in the agency’s history—to treat net neutrality as a public utility. To avoid the obstacle of reading through dense legal and technical material, the jargon used here needs a clarification. According to the FCC, net neutrality is referred to as “the principle of Open Internet,” in which consumers can make their own choices about what applications and services to use and are free to decide what lawful content they want to access, create or share with others. Both Republicans and Democrats agree that the Internet should be representative of one’s right to freedom of speech, but many disagree as to how the principle can be achieved.

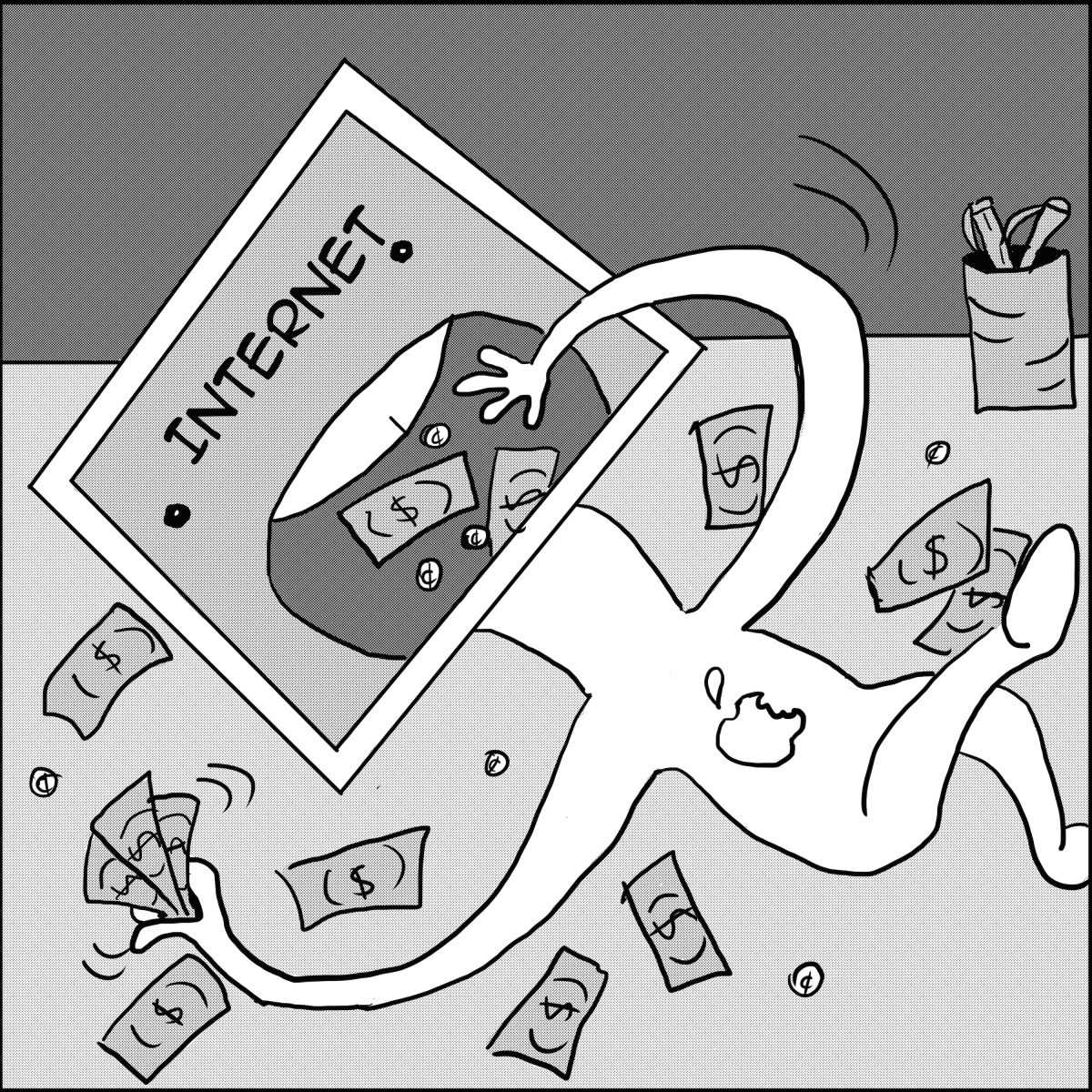

When people surf the Internet, depending on how much they pay for the speed to their Internet Service Provider, or “ISP,” they generally think that every website they access has the same speed. But things don’t work that way. Different sites use different access speeds; though, the difference is small to such a degree that most people can’t tell the difference. Almost all ISPs discriminate websites in accordance to the related traffic and charge higher rates for higher speed.

In 2010, the FCC issued a regulatory order that was intended to prevent broadband ISPs from blocking or interfering with traffic on the Web. Originally, the FCC’s rules prohibited wired ISPs from blocking and discriminating against content, while allowing wireless ISPs to discriminate against but not block websites. However, In January 2014, the court ruled against the FCC’s ability to enforce net neutrality because the legal framework was considered to be questionable and ambiguous. The FCC might face the lawsuits again this time as the new rules have sparkled fierce opposition from several wireless giants.

Michael Powell, chairman of the FCC from 2001 to 2005, told CNET that consumers would not see much difference in terms of quality and prices in the short run. But as the new rules go into effect, Powell said consumers are likely to see “higher bills from new taxes and fees and expenses related to regulatory compliance.” The FCC’s vote last week will allow it to regulate rates, set terms and conditions of business relationships, granting federal and state governments to impose taxes and fees on consumer bills. The cost of regulation will end up placing a burden on consumers.

But are consumers willing to pay the extra cost? Certainly, not all of them. But the new rules push the cost to a higher level for all wireless users. Some consumers will have no choice but to pay it eventually.

From an economic point of view, it is not difficult to see why ISPs discriminate websites based on traffic. ISPs have the technology to transform scarce resources into Internet services for consumers. But different websites have different frequency of visits. Popular social network sites such as Facebook, Twitter and news websites such as CNN have millions of visitors every day, whereas sites that specialize in smaller areas have fewer visitors per day. This frequency of visits can be seen as the force of demand. ISPs are motivated to put more resources and speed to support websites that attract more visitors than those with fewer visitors per day.

The FCC’s rules place constraints on an ISP’s ability to make decisions based on the data that it is more familiar with. Net neutrality ensures that ISPs treat all websites equally in terms of speeds, but doesn’t make efficient use of resources when considering websites that receive less traffic. These idle resources could have been used in websites where traffic is significantly greater. The increased cost will be transferred to consumers’ due to the monopolistic nature of the industry.

Besides, the more extensive a regulation becomes, the more difficult to implement and comply. The FCC rules give the agency substantial power and leave huge room for lobbying and distorting terms.

Send your thoughts to Ziyi at technician-opinion@ncsu.edu.