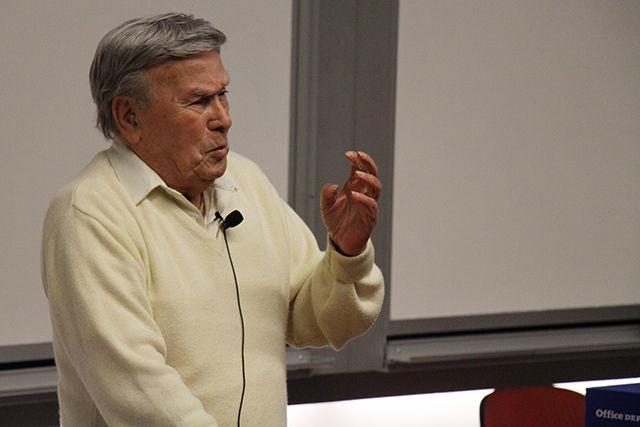

Holocaust survivor and the author of “Chosen for Destruction,” Morris Glass, spoke to more than 500 students and guests in SAS Hall Wednesday night.

In honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day, NC State’s Department of History invited Glass to share his story of survival.

“Morris Glass was 11 years old when the Nazis invaded Poland,” said Aaron Sugar, the nephew of Glass and a senior studying environmental technology.

After spending four-and-a-half years in ghettos, Glass spent two months in Auschwitz and eight months in five camps that were a part of the Dachau camp system, according to Sugar.

“During those years, he lost his youth, his father, his mother and his two sisters,” Sugar said. “Out of 42 close family members, only he, his brother and his cousin survived.”

Glass described his life before the war as a happy childhood, spent playing soccer and enjoying the company of his loving family.

“All of this came to an end on the September in 1939 when the Second World War broke out,” Glass said. “I was 11.”

The Nazis occupied Morris’ hometown within a week of the outbreak. They burned the city’s synagogue to the ground, and confiscated radios and books.

“A short while later, the ghetto was formed,” Glass said. “We were all forced to work for the Nazi regime, producing many valuable items, such as shoes and boots, to be sent to the eastern front.”

Glass said that what kept him going was his faith and the fact that he was still with his family.

When it came time for Glass’ hometown to be liquidated, he, along with all of the others currently living in the ghetto, were marched to a soccer field.

“To describe that night —the crying, the pleading— is almost impossible,” Glass said. “I remember one incident in particular. This SS Stormtrooper grabbed a baby out of its mother’s arms and threw it against the concrete wall. The baby fell lifeless.”

The able bodies were then moved by cattle cars to the Lodz ghetto. Here, there were anywhere from 200 to 300 people dying every day, according to Glass.

“It was not unusual when someone passed away for the family to keep the body for a week or so until the rations came out,” Glass said. “This way, they could benefit from the additional food.”

In the spring of 1944, Glass, along with his father, mother and two sisters were put into cattle cars and sent to Auschwitz.

“When we disembarked, the men went to the right, the women to the left,” Glass said. “I saw my mom and my two sisters. I waved at them and I never saw them again.”

Glass and his father were led into a small room where they were forced to undress completely, have their heads shaven, shower and dress in a striped outfit.

Glass and his father spent the next two months at Auschwitz, a place that Glass said is indescribable.

“The women, I saw them,” Glass said. “Their heads shaven, their faces showed unreliable pain. Walking on all fours, not the slightest resemblance to humans.”

After Glass and his father were moved out of Auschwitz to another concentration camp in Germany, Glass watched in unbelievable horror as his father was murdered for his gold crowns.

“They were pulling the teeth from his mouth, his body still warm,” Glass said.

Glass recalled the painful lashings he received from Nazi commanders, as well as his bout with dysentery.

On April 28, 1945, after escaping from the Nazis while on a death march to southern Germany, Glass saw an American tank.

“I cannot possibly describe the feeling of seeing an American tank,” Glass said. “We ran out and we hugged them and kissed them. We went bananas.”

Seventy years later, Glass is grateful for the opportunity that the United States has given him.

At the end of his speech, Glass asked the audience for one favor.

“On behalf of all of the millions who perished in the Holocaust, and on behalf of the survivors who are no longer with us, I ask you to never forget the Holocaust,” Glass said.