In response to the controversy spurred by the release of the abuse-glorifying “Fifty Shades of Grey” movie, fans of the original books often relay, “They’re just books. They don’t mean anything.”

This is a popular mindset to adopt. It is comforting to think that we can compartmentalize our mental processes to the extent that the content we imbibe makes no lasting effect on us. We can watch violent movies, keep up with racist television shows and read books that support systems of abuse and claim that we, as individuals in charge of our own person, maintain the sole responsibility for how we learn and grow. But that simply isn’t true.

While entertainment can influence trends, it can also reflect them while further perpetuating them. In response to “American Sniper,” many people made racist asides on Twitter, such as the following statement: “American sniper made me appreciate soilders [sic] 100x more and hate Muslims 1000000x more.” Though it cannot be rightly said that “American Sniper” instilled such values directly, its content further encouraged pro-war and anti-Muslim sentiments.

Although most may not perceive films as propaganda, many movies hide agendas while claiming to only be entertainment. Movies that openly tout their progressive nature (such as “12 Years a Slave” and “Milk”) use this to their advantage while movies hiding harmful propagandist substance carefully shift discussion away from anything problematic that might be contained within their scenes. Filmmakers claim their products mean nothing if they encounter negative criticism. Meanwhile, they wear positive comments like badges.

The problematic content in “Fifty Shades of Grey” should not be dismissed as “just” entertainment.” Entertainment has the power to transform people, as well as shape history itself. The “Harry Potter” series created a generation of fantasy lovers who continued to read into adulthood. “To Kill a Mockingbird” caused many to pay further attention to the racism strongly permeating the American South. “Mein Kampf” greatly influenced the growth and corruption of a nation, in addition to leaving a catastrophic stain on history itself.

The “Twilight” saga largely ignited the current trend of romanticized abuse in genre fiction (those readers have since graduated to “Fifty Shades,” the fanfiction based on the characters of Bella and Edward).

On Tuesday, police arrested a 19-year-old student at the University of Illinois at Chicago for raping and beating his fellow student. Prosecutors have identified the attack as “a re-enactment of scenes” from the movie adaptation of “Fifty Shades of Grey.”

In addition to misrepresenting the inherent importance of consent in sadomasochistic practices, “Fifty Shades” tells a story of abuse insidiously disguised as romance. “Twilight” and “Fifty Shades of Grey” are not merely pieces of smutty romance that we may enjoy without concern; they have become justification for assault. One should not desire to have a relationship like Bella and Edward’s, in which the power dynamic is so one-sided and patriarchal that it seems Bella never acts without permission. Yet so many people aspire to obtain this perverse, dangerous ideal.

Though many may be tempted to categorize this assault as a rare occurrence and mark the aggressor as unstable, it is essential that we recognize such events as symptoms of a larger issue rather than completely remove context and ignore that something is wrong. Myriad women have come forward addressing how their “Twilight”-esque relationships do not reflect romance, but rather reflect their abusive circumstances. These women have not found the love of their life. They are scared.

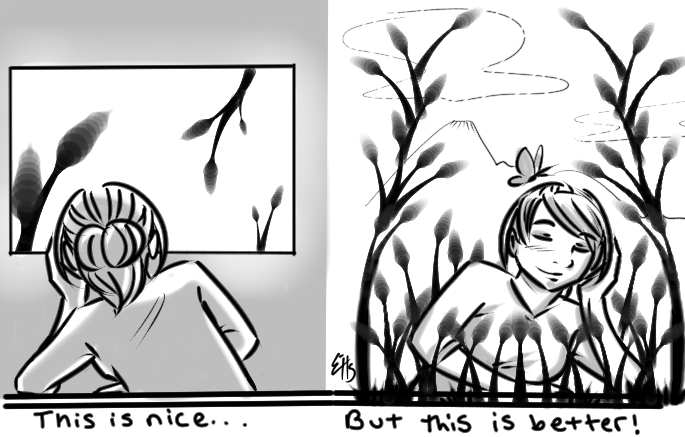

Everything we consume may very well possess an idea, and we must acknowledge how ideas spread. It isn’t enough to believe that the media we enjoy will not affect us in the end. To ignore the impact popular entertainment plays in our culture is to ignore the consequences that it may bring about as we unconsciously absorb problematic content.

It is necessary that we learn to consume entertainment with a sense of awareness. A book is not “just a book.”