During the past 13 years, we have become inured to the fact that we are at war. The citizens of the United States have all but accepted the constant state of wartime, and, in many cases, we can ignore it completely.

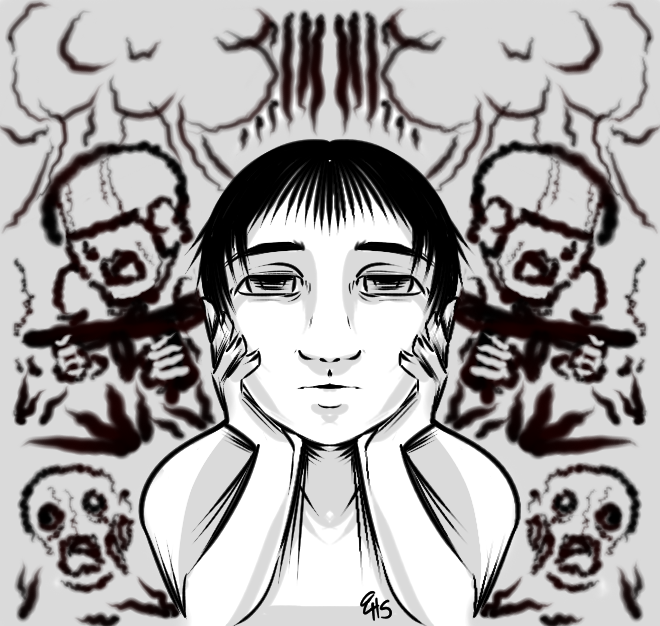

Many factors contribute to the overall desensitization of the U.S. public regarding the so-called “Global War on Terror.” Though I will hardly be able to touch on most of them, I hope to highlight a few, including the omnipresence of dramatized, often violent images and the overt glorification of the war effort.

I hardly want to assert that violent content instills violent character or directly makes people who absorb it do violent things. Though many researchers have endeavored to prove a link between the consumption of violent media and violent actions, few have done so without incorporating personal bias. However, a common thread that connects many studies seems to indicate that consuming violent content does increase the likelihood of believing a violent act to be acceptable.

A group of scientists led by Craig Anderson, a distinguished professor of psychology at Iowa State University, found that while children who played video games in general actually demonstrated a decline in aggression with age, children who played violent games habitually displayed an increase in aggressive thinking. Along these lines, in being constantly bombarded by violent media and exaggerated news stories, we develop a tolerance to what should naturally be shocking or upsetting. Violence becomes noise in the background.

In addition to the desensitization stimulated by the omnipresence of sensationalized, violent content, the media frequently numbs us to the more serious (and often sacrificial) aspects of the war effort. Movies like “Act of Valor,” “Lone Survivor,” and, most recently, “American Sniper” serve as propaganda with a dual focus—to both glorify soldiers, thereby promoting them to sainthood, and to support the war effort without criticizing any aspect of it.

The vague “Support Our Troops” ideology has become incredibly pervasive as well as mindless. It has become an oft-repeated mantra, and though it trivializes the state of war and compartmentalizes the war effort as something entirely separate from regular citizens, it is considered sacrilegious to question it.

People who question the slogan are deemed “un-American” and accused of apostasy (which regularly seems to be the worst thing one can do as a United States citizen). “Support our troops,” though they may be violating human rights overseas. “Support our troops,” though we might not agree with the current manifestation of the war effort. “Support our troops,” though those troops might be being mistreated by their country rather than by those “enemies” we trust to exist.

We reiterate “support our troops” to bolster the already illustrious reputations of the faceless sainted soldiers who, generically, “fight for our country.” Yet when veterans return from their battles and their status of soldier is essentially removed, they are systematically shunned from the notion of glory that their role promised them. Such was the case of Omar J. Gonzalez, the war-damaged veteran arrested for trespassing at the White House after years of being refused the medical attention he needed.

It is problematic, to say the least, that we have adopted a general complacency towards our nation’s extensive involvement in other countries, and perhaps even more so that we venerate soldiers in lieu of actually thinking of them as people that are often discarded for the sake of justifying causes that perhaps should have already been concluded.

Through our being surrounded by the sensationalized media we view as separate and “fake” and the combined glorification and commodification of soldiers (amongst other enumerable factors), we are able to separate ourselves from the reality of war. And it seems that we can’t find it within ourselves to care.