The North Carolina Museum of Art will feature the “Codex Leicester,” a personal manuscript from Leonardo da Vinci, for a limited time. Accompanied by an exhibit of work by artist M.C. Escher, the museum focuses on ideas of innovation and how logic and reasoning can be incorporated into art.

The “Codex Leicester” is da Vinci’s only manuscript in North America. Currently owned by Bill Gates, the “Codex” has been displayed in museums around the world from the Chateau de Chambord in France to the Phoenix Art Museum. However, this is the first time in seven years it has been debuted, and the North Carolina Museum of Art was chosen as one of three locations in the United States to display the manuscript on this limited tour.

According to David Steel, the curator of the exhibit, the Bill Gates Foundation chose the museum to host the “Codex” because they felt that the NCMA, being in the Research Triangle area, was the center of a “community of innovation.”

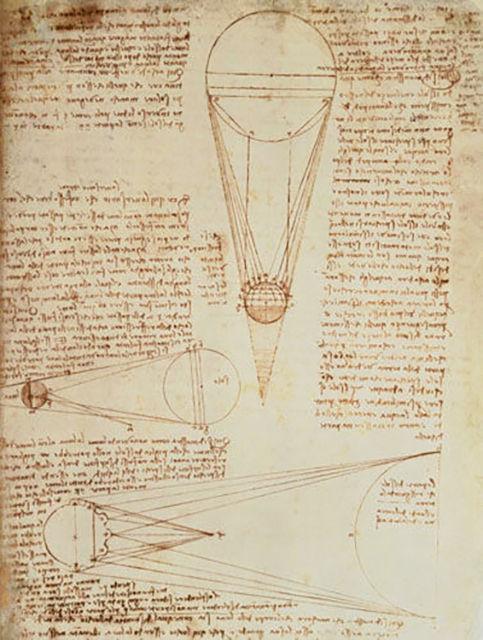

Innovation, thinking and design are the main themes that come across in the “Codex” exhibit. It provides a look into the detailed observations, speculations and hypotheses of a man who is considered one of the greatest minds in history. Questions and explanations about topics of the physical world—from water and how it moves, to building canals and questions of Earth’s functionality—are written out in da Vinci’s impeccably neat, mirrored handwriting across a series of 36 pages, with detailed drawings and notes in the margins as well.

In the museum’s exhibit, “Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester and the Creative Mind,” the pages of the manuscript were displayed each in its own glass casing. Visitors could walk up and closely analyze the pages, being able to read them right at eye level. Though da Vinci wrote in Italian and backward, under each display the words are explained in a brief description that describes the ideas he wrote about as well as their connection to the rest of the work. The museum features tablets, called Codascopes, where guests could look at an individual page in a translated version to get a deeper look into da Vinci’s thoughts.

Leonardo often talked about these topics in both a scientific and a philosophical way. Chris Vitiello wrote in a review for Indy Week, “ … his poetic moments are just as instructive, if not more so, in their fusing of art and science into inspired inquiry.”

The room was dark to minimize light exposure to the pages, giving off the illusion that each page was glowing in its display, intensifying the feeling of importance about what you were looking at and who this person was.

“People should come away with seeing how his brain jumps from one thing to another,” Steel said. “You can understand how Leonardo thought, and this was the man who invented thinking on paper.”

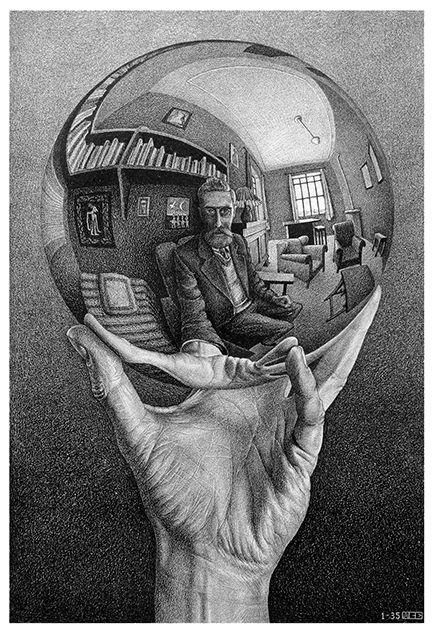

The “Codex Leicester” accompanies another exhibit at the museum titled “M.C. Escher: Nature, Science and Imagination,” which displayed the works of M.C. Escher, an artist from the early 1900s. Escher was known for his mathematically inspired woodcuts, graphic designs and tessellations.

In this exhibit, which was more visual in nature than da Vinci’s, guests can walk through a number of rooms, each with various works by the artist, ranging from a number of different mediums and a variety of techniques. Accompanied with some of the finished works are sketches of drafts where he practiced drawing specific sections of the picture, helping viewers see the progression of how each piece came together to make the final picture.

Escher focused so much on small details that even pictures that are just pencil sketches on paper have intricate designs, and when looking closely, you can see took careful and organized planning. In the exhibit, there is a description of Escher that said the artist felt he had more in common with mathematicians than his fellow artists, and guests can see that by his emphasis on geometrics in the designs of his pieces and the way each work seemed calculated down to every line.

By going through the exhibit, guests get a strong sense of what went on in the mind of Escher when he approached his pieces and learned who he was as an artist.

Steel, who is the curator of the Escher exhibit as well, said there is a strong similarity between the two shows and the two artists.

“They are both keen observers of the world around them and use mathematical logic to view the world, and we can see that in the way they think on paper,” Steel said.

When the opportunity to display the codex was presented to the museum, Steel said he knew this would be a great addition to the Escher exhibit. The exhibits demonstrate how two artists from completely different eras both can show innovation and design in the displayed works. In both, he said we are seeing how these men think and can see the value of what thinking on paper was. Both artists used logic and reasoning in artistic ways to express different elements of the world around us.

A quotation displayed on one of the walls of the museum by Escher read, “When you read Leonardo’s notes, you can hear him speaking like a lonely, wise and melancholy great man … I seem to recognize the same silent wondering as my own.”

See “The Worlds of M.C. Escher: Nature, Science, and Imagination” and “Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester and the Creative Mind” on display at the North Carolina Museum of Art until Jan. 17.

M. C. Escher, Hand with Reflecting Sphere (Self-Portrait in Spherical Mirror), 1935, lithograph, 12 1/2x 8 3/8in., Collection of Rock J. Walker, New York, © 2015 The M.C. Escher Company, The Netherlands. All rights reserved. www.mcescher.com