When the trailer for “Concussion,” a true-story-turned-movie starring Will Smith, was released in late August, it served as an encore performance at the figurative pity party for the NFL’s bigwigs and its franchise executives. As if the league hadn’t already been dramatized enough during the past year, the upcoming thriller — set for release on Christmas Day — will detail the story of Bennet Omalu’s research into the potentially deadly long-term effects of football-related brain trauma.

With a release that coincides with the penultimate week of the regular season, there’s no question the movie will be an unwelcome distraction for the league at its most critical time for engendering playoff viewership. The real concern for the NFL is far more long-term in nature: Will increased awareness of the game’s dark secret incite a moral tirade and force the league’s hand in adopting even more concussion-sensitive policies, potentially watering the game down beyond comprehension?

That obviously depends on several factors, chief among which is whether or not “Concussion” pulls any punches in its vilification of the NFL’s highest leadership, who were content with brushing this issue under the rug ad aeternum.

Since the trailer’s release, The New York Times has reported that some “unflattering” material was in fact cut from the movie’s final edition — as gleaned from the infamous mass-leak of Sony emails. But take this information with a grain of salt; not only is it vague, but it’s likely typical of any major studio release. This information just isn’t usually made public by a group of Korean hackers, meaning it might just amount to the removal of some borderline libelous content. This is, after all, the same studio that released “The Interview” amid highly aggrandized international controversy, so it’s doubtful that it would undermine its own film’s impact as some sort of favor to the NFL — an opinion bolstered by the trailer’s inclusion of a scene in which Smith’s character implores NFL representatives repeatedly to “tell the truth!” Spoiler alert: They don’t.

What’s working against “Concussion” is that much of the damning material to be presented has already been made public in the form of book and documentary “League of Denial,” as well as countless other mini-documentaries, where it has failed to instigate a meaningful reaction from the NFL. It’s even possible that the word “concussion” is losing efficacy in the battle for its prevention as its range of diagnosis expands to cover more mild head trauma. Potential evidence of this lies in high school football participation rates, which rose in 2014 following four consecutive years of decline. For 2015, rates dropped but by less than 1 percent.It seems parents have taken some time to consider whether dashing the risk of concussions is worth pulling their child out of the sport, and just a small portion have decided it is.

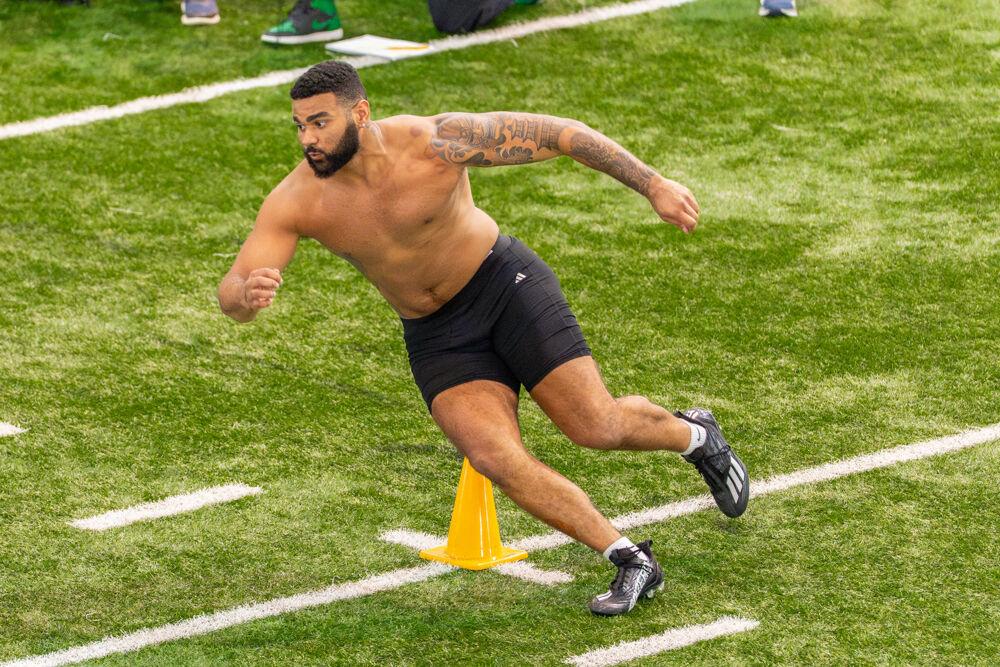

So, if parents aren’t going to use “Concussion” as fuel for igniting mass-adaptation of the game of football, who will? The answer: the athletes themselves. No, I’m not talking about little Timmy down the street. I’m talking about his big brother Jimmy who was 6-foot-2, 230 pounds with a full-grown beard by junior high and is now making a career for himself by using his body—including the head—as a weapon.

Professional athletes have to be the ones to take advantage of this film because they are the ones with the most at stake. Ironically, the central focus of “Concussion” is not concussions; it’s chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease that currently can only be diagnosed postmortem. It’s responsible for driving professional football players toward suicide later in life and the result of more excessive brain-beating than just a concussion or two.

While it’s unlikely that “Concussion” can be powerful enough to motivate millions of everyday Americans to adopt the cause, it’s possible that it will generate enough furor among professional athletes to make a meaningful difference which, quite sadly, is unlikely to come until the NFL and the Players Association renegotiate their collective bargaining agreement for the 2021 league year. Until then, it will be difficult for the players to leverage any significant revisions to the current safety protocol. The end result: at least six more seasons of the traditionally violent playing style that has blossomed into a now $11.2 billion industry that Americans just can’t get enough of.