Many may know ESPN for Sports Center, but its second longest running show on is the STIHL Timbersports , the top-tier competition for lumberjacks across the world.

Hundreds apply each year, and only the top 40 competitors are accepted to compete for the championship title. N.C . State hosted the southern regional competition this year, and had several students and alumni competing.

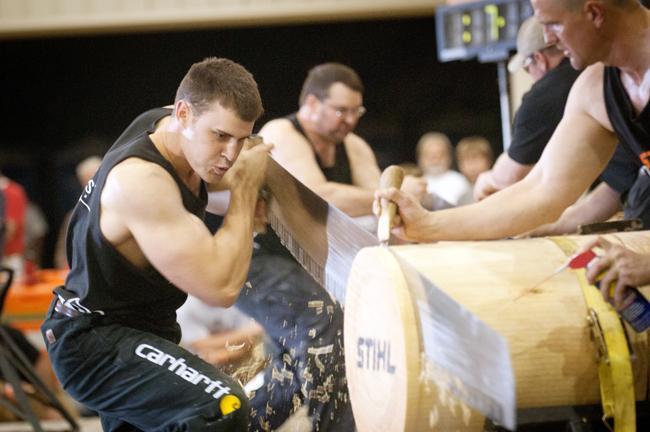

Six categories comprise the event: the springboard chop, the stock saw, the standing block, the single buck, the underhand and the hot saw. The most amusing for spectators to watch is probably the springboard chop event, which involves climbing up trees and cutting them down.

“What it used to be is a way to get around knots and trees and old broken timber… the old way to chop off wood at the top of the tree was to put these planks of wood in the tree,” Brad Sorgen, the producer of the STIHL Timbersports series, said.

The athletes chop small holes into the sides of trees and then jam in planks called springboards, which they use to climb up at least nine feet. There they race to chop off the 12-inch top of the tree.

“It’s entertaining and scary – if you don’t have your boards set into the tree very well you have the possibility of falling and getting injured,” Sorgen said. “And you’re not only falling nine feet, but you have planks of wood in the way and your axe in your hand.”

Logan Scarborough, an N.C. State alum and forestry consultant, admitted that it was a bit dangerous – he unfortunately fell off a board during the competition – but that doesn’t slow him down. Two years ago he earned the title of U.S. collegiate champion and is competing as a pro this year.

“If you play with sharp objects you’re going to get cut, you know?” Scarborough said.

If all the safety precautions are followed, there generally aren’t many mishaps.

“You don’t see injuries that often – you just see speed, power and precision,” Sorgen said.

Another one of the more exciting events is called the hot saw, in which the competitors race to make three six-inch cuts using their own custom-modified chain saws. The saw motors have been replaced, usually with outdoor watercraft engines or motorcycle engines, making them so powerful the world record for this event is only a little over five seconds.

“The chain speed is moving at around 200 mph and it’s got 6s horse powers,” Sorgen said. “These machines are loud, they’re screaming and they just burn through the wood.”

This was one of Scarborough’s favorite events because it combines ingenuity with athleticism.

“Hot saw is a lot of fun – it’s aggravating sometimes, but when things go your way it’s really self-gratifying. There are so many things that go into it,” Scarborough said.

Sorgen, however, favors the steel stock saw event, where athletes use identical chain saws to cut precisely measured “cookies” of wood off of a log.

“You can practice all of the rest of the disciplines until you’re blue in the face. The stock saw is one where no matter how hard you practice, anything can go wrong in it… ultimately it comes down to your precision at using a skilled tool,” Sorgen said.

Victor Wassack, a senior in forest management, competes in the four collegiate events — the single buck, the standing block chop, the stock saw and the underhand chop.

“I got into timbersports when I was a freshman in college,” Wassack said. “I was in the forestry program and one of the clubs was, of course, the forestry club.”

Wassack has a promising start as a timbersports athlete. Last year he finished second, and this year he won the Southern Qualifier and will be going onto the Collegiate Championship this summer.

“I would definitely like to go pro,” Wassack said.

Going onto timbersports seemed like a natural progression for Wassack, who played outfield on his high school baseball team and found himself in college without a sport to participate in.

“I played baseball through high school, and in college I wasn’t really doing anything, so instead of a baseball bat in my hand I had an axe,” Wassack said.

Scarborough also played baseball in high school, as a first baseman. While baseball does lead logically into timbersports, he said that it was a bit of a difficult transition. Scarborough recommends imagining that you are batting pop-flies as you swing your axe, rather than a more natural baseball swing.

“You have to break that swing completely,” Scarborough said.

However, many other aspects of baseball do carry over. Wassack believed playing baseball through high school has helped him in his timbersports career.

”There’s a lot… you’ve got to be very active and you’ve got to have good hand-eye coordination,” Wassack said.

Scarborough was in agreement with Wassack, saying that the sport has more precision to it than most people first believe.

”It’s a sport derived from lumberjacks back in the day, but when people hear that they think of it condescending a little bit… it’s a really fair sport, and it’s just like everything else – if you get good at it, it’s definitely worth watching,” Scarborough said.

‘Getting good’ at timbersports does mean being physically fit – one of the ways to train is weightlifting according to Wassack – but practice, skill, and strategy are the more important aspects.

“It’s completely different in timbersports. If you’re 53, 52… you can beat everybody,” Scarborough said.

Right now, despite its popularity on television, the sport is rather unknown, and so it forms a small, tight-knit community of competitors.

“The athletes that participate in the sport aren’t full time lumberjack professionals – a lot of them are teachers, we have a couple who are lawyers or construction men, and they just happen to do this for fun because it’s been in their history and the heritage that’s been passed down in their family,” Sorgen said.

Scarborough enjoyed the atmosphere this creates, saying that older competitors will help younger ones by teaching them how to modify chainsaws or by perfecting their swings.

“Everybody knows everybody,” Scarborough said.