Nasher Museum

Grant Hill has jokes. Even amidst the chaotic scene of his art exhibit, standing in front of a large crowd of cameramen, pushy reporters and timid high school kids, Hill just seems like a normal guy talking to some friends. Never mind the microphones thrust in his face, the herd that follows his every move or the massive television cameras causing every other person to duck as they swivel for Hill’s best angle.

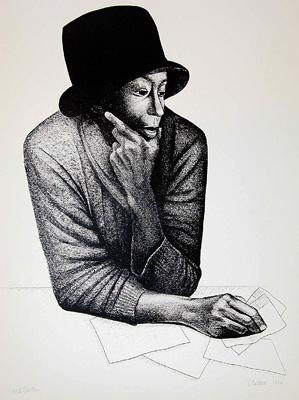

For him, this media circus has become standard routine; he focuses instead on communicating with the faces around him, speaking softly with a grin on his face about John Coleman’s Coffee Break.

“My dad likes to say as a parent there [are] six inches between a pat on the back and a pat on the butt, and sometimes as a parent you have to do both,” Hill said.

Hill’s contribution to the art community entitled Something All Our Own: The Grant Hill Collection of African-American Art has traveled around the United States for the past two years, making stops everywhere from the Basketball Hall of Fame to the Dallas Museum of Art. Hill’s alma mater is last stop on the tour, the collection settling in from now until July 16 at the Nasher Museum of Art.

Looking at his grey power suit, fashionista pink shirt and tie and large frame, most would expect something entirely different from the incredibly friendly, soft-spoken man before them.

As Megan Hotchkiss, a junior in English put it, “What in the world would make a basketball star collect art?”

Hill’s story begins with a big house and a lot of wall space.

“For me,” Hill said, “[art collecting] started as wanting to decorate — it’s as simple as that.”

The desire and appreciation for art did not hit Hill until after collecting began, even though he had been exposed to wonderful art from a young age.

“I grew up in a household where there was a lot of art, not just African American but Native American and African art, third world art, and I didn’t particularly enjoy it,” Hill said, smiling. “I didn’t have an appreciation or understanding of it. It’s pretty safe to say I didn’t like it at all.”

“But it does have an effect,” Hill said, launching into a story about his daughter. “When this exhibit first opened in Florida, a lot of these pieces were on the wall of our home before. And my daughter, who is now four, was probably almost two, was able to remember the pieces. And just as I have gotten older, I have caught on a lot of what my parents tried to do.”

The collection Hill has built in the past 10 years has become an intimate look into his soul through the works he finds beautiful. He has gone beyond the stereotypes of what creates fine art, instead desiring works that speak to him. And he wants to share these words with everyone.

“I didn’t come from a technical side; I didn’t take any art history courses. I’ve done a little reading and studying over the past 10 years, but for me it’s really a matter of what I like,” Hill said. “I have some pieces by some artists [who] are considered masters, and then there are some by artists like Edward Jackson [who] are more contemporary, maybe not as known… [but] they are snapshots of our history… they remind me of something I read about, remind me of stories my parents, my grandparents, my great grandmother shared with me about our family, our history, our race.”

The foyer of Hill’s home used to display a rather dominating portrait of Malcolm X expressed in a spectrum of blues by Edward Jackson. “I bought this the same time I bought my first house and I hung it on the wall right when you walked in the front door,” Hill laughed. “I don’t know if it scared people or not.”

For Hill there is always a much deeper meaning, even if he talks about being ignorant of accepted professional terms.

“I bought [Malcolm X] at the San Antonio gallery in 1996 at the NBA All-Star game,” Hill recalled. “When I was in 1993, the movie about Malcolm X by Spike Lee came out, and I had read the autobiography, and I just felt the ways he was portrayed are my reasons, he was always serious, very stern, and militant. I felt that this piece softened him up a little bit, shows the human side; the colors, the smile on his face, relaxing enjoying himself.”

The immersion of his self into art began with his parent’s influence, but branched to include his wife Tamia, his daughter and now the nation. Hill’s love for his family can be observed through the way he describes art, the way he adds stories about his family to explain a piece and the way he praises his wife’s accomplishments.

“The only art I try to do is on the basketball court, and lately I haven’t been too successful at that because of injuries,” Hill joked. “But my wife is a recording artist, and I have a healthy appreciation and respect for what she does and for what these artists in the museum are doing.”

Hill doesn’t hide his desire for the exhibit to spread the joy he has found in African American art with the world, especially with students.

“I hope, in my celebrity, that maybe people who wouldn’t normally visit a museum will come,” Grant said. “And just like my experience at museums and galleries had a lasting effect, hopefully it will have that on those who normally wouldn’t visit; I just think exposure is important.”