It was about 2 p.m. July 12 when she first heard about it.

Danielle Touma, a sophomore in civil engineering, listened as a reporter on the news informed her that Hezbollah forces had kidnapped two Israeli soldiers.

It wasn’t incredibly important to many American citizens — just another news flash. Even to Touma, who arrived in Lebanon June 23 to visit her parents, it wasn’t quite cause for alarm.

“You always hear about conflicts in the south of Lebanon that [don’t] usually affect anyone else,” Touma said.

But a day later, all that changed.

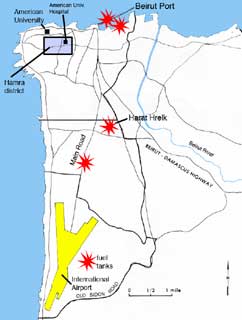

After fighting in southern Lebanon throughout the night, Israeli jets bombed the runways of Beirut’s international airport the next day.

From her parent’s house in the middle of Beirut, Touma said she heard the attack and went to a friend’s house who lived on the 13th floor. From her vantage point, she said she could actually see what was happening.

It was an experience she said is hard to imagine.

“The bombings are just scary — I can’t describe it,” Touma said. “To put it in blunt terms, I just want to throw up each time I hear something.”

Over the next few days, the bombing continued.

Her father stayed home from work since the road to his office passed by the bombed airport. The streets of the city emptied. The shops closed down.

Beirut had become a ghost town.

“The thing is, you can hear two things: either the sonic boom from the planes or the bombs,” she said. “It’s hard to tell the difference, so we always assume the worse.”

In the meantime, Touma said she spent a lot of time with her family — especially her cousins, who were in town from Canada to see their uncle get married. They mostly watched the news, and when their parents got tired of it, they watched movies.

Occasionally, though, the power would go out. “That’s when we read a lot.”

“I guess it has been a bonding experience except for a really bad reason,” she said. “We just keep ourselves occupied so we don’t think of it.”

Although she said she is concerned about her safety, her parents house is in the Hamra district and very close to the American University Hospital. She said her mom is convinced they are safe where they are.

Actually, Touma said, there are much bigger concerns on her mind than safety.

When will the conflict end? How will she leave if the conflict lasts for a while? What will her parents do if she evacuates?

All are questions, Touma said, that are constantly running through her mind.

One of her cousins has family in the U.N., and because he was under 18, he needed someone of age to escort him to a bus waiting in Syria. Given the option of evacuating, though, Touma declined.

“I would have gone if I knew about it at least a day in advance, but I couldn’t emotionally leave my family, or physically pack my stuff after being woken up at 9 a.m. and being told about it,” she said.

Although she had registered with the U.S. Embassy when she spoke with Technician via instant message Sunday night, she said she hoped to learn of evacuation plans over the course of the week.

“I’ll probably go for it, it just hurts to leave my parents in a situation like this,” she said.

But if her parents have anything to say about it, Touma will be leaving as soon as possible.

“They want me out of here ASAP basically,” she said. “They’re scared [my sister and I] will wait too long to leave and then it will be too late for a while.”

Critics have chided the U.S. for its slow response in evacuating its 25,000 citizens from the area. But according to Akram Khater, associate professor and director of international programs, this may be partially due to the weak position the U.S. is in with many factions in the Middle East.

“We have involved ourselves in the Middle East in such a manner as to not have a lot of credibility,” he said.

According to the Web site of the U.S. embassy in Lebanon, about 6,000 U.S. citizens will be evacuated over the next two days. Technician, however, could not confirm whether Touma had evacuated by press time Wednesday.

In the meantime, however, Touma said her wish is that Hezbollah and Israeli forces will stop the violence, which she said has sent Lebanon back in time 20 years or more.

“Like a lot of people, I want Hezbollah out. But then again, I don’t think it should be done through war and violence,” Touma said. “This is one of the very few regions where conflicts still happen like this. It’s ridiculous.”

Ceasing the conflict might be difficult now, especially according to the beliefs of some analysts, who said that Israel is now less concerned with the return of its soldier and more about driving out Hezbollah.

“As all Lebanese know, this war isn’t about their soldiers. Even if Hezbollah returned their soldiers safe and sound, Israel would continue the attacks until Hezbollah was fully unarmed,” Touma said. “The capturing of the soldiers was just a trigger.”

Khater said this was “absolutely the case,” especially given the speed and ferocity with which Israel launched their attacks.

“You don’t go around ad hoc picking targets,” he said.

He said the only way to stop the violence is to force the two sides back to the negotiating table and to peace talks, instead of the situation now where Israel sets all the terms.

“There has been a stalemate,” Khater said. “That is not satisfactory to the other parties.”

The U.S., however, is the only country that can push Israel into this position, Khater said, especially since the U.S. is often Israel’s only ally.

“The U.S. needs to be an honest broker for peace in the Middle East,” Khater said.

Despite the escalation of violence over the last few days, and in the face of speculation from some that Syria and Iran may enter the conflict, Khater said he only expects the fighting to go so far.

“The rhetoric, in many ways, is for local consumption,” he said. “They’re willing to bluster but not willing to go into direct confrontation.”