Something had changed inside Aaron Bates.

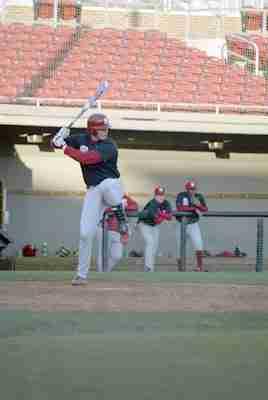

As he dug his feet into the Doak Field sand and shifted his colossal 6-foot-4 frame into a batter’s stance, everything about Bates appeared different.

His California-fueled smile and beaming blue eyes faded into a deadpan stare. A fierce determination replaced his casual antics and his go-with-the-flow demeanor.

It was as if the world around him and everything in it had disappeared — everything, that is, except the baseball.

The pitcher wound up and fearfully fired a pitch towards Bates. With a lightning-quick swing followed by a thunderous connection, Bates sent the helpless ball sky-rocketing over the center field wall. Put another tally in the homerun column for Aaron Bates.

The pitcher stood, staring out towards center field, as if waiting for a window at Lee Hall to shatter in the distance. After gathering himself, the pitcher closed his jaw and flashed a half-hearted grin at Bates. Bates’ California smile reappeared as he reset his feet for another pitch.

It was, after all, just batting practice.

But there won’t be many pitchers smiling when Bates is up to bat this season.

The returning All-American first baseman is coming off a season that was one of the best in Wolfpack history. Bates belted 12 home runs, 64 RBIs and he batted .425 — the second-highest average in the league.

State coach Elliot Avent linked Bates’ offensive abilities to legendary Red Sox slugger Ted Williams, whom some revere as one of the best hitters in baseball history. Though comparing anyone to Williams may seem suspect, Avent sees similarities between the two — most notably, their intelligence at the plate.

“The thing that separates Bates from a lot of hitters is his mental approach,” Avent said. “His hitting I.Q. is incredible.”

Bates said hitting is an intensely individual affair — an art that one ultimately has to master on his own.

With the field as his canvas and a bat for his brush, Bates has painted a picture of hitting perfection. While many in the baseball world were taking notice of Bates’ offensive artistry, others tried to purchase it with an eighth-round pick.

Major League Material

Bates was at teammate Brian Aragon’s house when he first got the call. It was June 2005, and the two had just returned from the Pack’s early and unexpected departure from the NCAA tournament following a loss to Creighton.

The Florida Marlins contacted Bates to inform him that he’d been drafted in the eighth-round of the 2005 Major League Baseball Draft. For Bates, the call was the culmination of a life lived in the weight room, film room and batting cage.

“I was extremely honored to be drafted by the Marlins,” Bates said. “Playing pro baseball was something I had been working for since I was little kid.”

But the little kid in Bates had grown up. Wanting to play in the majors, but also wanting to continue working towards an academic degree, Bates decided to talk things over with Avent.

After listening to Bates’ testimonies, Avent was confident his first-rate first baseman wasn’t going anywhere.

“Everyone had decided he was going to the Marlins — everybody was ready to sign him up to play,” Avent said. “But when I was sitting there listening to him, it was clear to me that I was talking to a guy who wanted to come back to college.”

The Marlins called Bates one last time to wish him good luck in the future. Financial talks had all but ended, and the team knew they wouldn’t be seeing Bates in Miami anytime soon.

With his major league aspirations put on hold, Bates had essentially chased, captured and walked away from a lifelong dream.

A California Dream

It was around kindergarten when Bates decided he was going to be a professional baseball player.

Growing up around the bay area of California in Santa Cruz, Bates started playing baseball at age five when his father, Mark Bates, snuck him onto a little league team.

The cutoff for the league was seven, but since Bates was one of the biggest kids on the team, no one questioned his eligibility.

The team eventually got wind of Bates’ age, but no one had the heart to tell the 5-year-old he couldn’t play anymore.

So Bates was allowed to continue playing. At the season’s conclusion, he made a claim to his parents.

“Aaron told us when he was six that he was going to be a pro-baseball player,” Aaron’s mother, Joann Bates, said. “He said it was his dream to play in the major league.”

While Joann admitted Bates was a chronic daydreamer as a child, she said she and her husband didn’t doubt their son’s assertion for an instant.

No sport was left unexplored by Bates while growing up. He was a goalie in soccer, a forward in basketball and the starting quarterback for California’s Archbishop Mitty High School — leading the Monarch to a 12-1 record his senior year.

But his dreams remained diamond-shaped. After a prestigious high school career, Bates accepted a scholarship to play baseball for San Jose State.

He enjoyed a successful freshman season at SJSU, where he was named second team All-WAC as a designated hitter.

While his life seemed solid on the field, things were getting shaky off of it.

His advisor at SJSU inexplicably told Bates to sign up for a class that he wouldn’t receive credit for. Bates, following the flawed advice, took the class, yet received no credit for it.

The move left Bates one credit short of a full course load. It also left him academically ineligible for the 2004 season.

Although the situation was eventually corrected by the SJSU staff, the resolution was too late. Bates had decided to pursue his college degree elsewhere.

Bates faxed his release to approximately 25 schools, and received interest from several programs, including N.C. State.

He took a recruiting trip to Raleigh the day before the Pack headed to Miami for the 2004 NCAA regionals.

Bates said he knew almost instantaneously that he belonged at NCSU. He fell in love with everything about the University and gave a commitment to the coaches while on the visit.

“I just went with an impulse, a gut feeling that told me that [Raleigh] was the place I belonged. Plus, I needed to get out of California,” he said with a grin. “I was getting spoiled over there.”

Joann, who had attended nearly every one of Bates’ games since his renegade little league days, was initially apprehensive about the distance between her and her son. But she eventually warmed to the idea of her son living and learning in a different part of the country.

“I was happy that he had found a place [where] he really wanted to be,” Joann said. “I decided that if N.C. State was going to make him happy, I didn’t care how far he was from home.”

With a new lease on his baseball life, it seemed the pieces were finally falling in place for Bates. Then in June 2004, just when things were looking up, Bates got a call from his mother. His father had suffered a heart attack.

A Hero Lost

Bates was in Los Angeles with his older brother when the two received the news that their father was in the hospital. The brothers drove up the golden coast through the night, and arrived at the Santa Cruz hospital at 3 a.m.

But they were too late — Mark Bates had already passed away.

“It just all happened out of nowhere,” Bates said. “It was just out of left field.”

Bates said he lost more than a father that day. He lost an advisor, a coach and a close friend.

With the fall semester starting back in a few months, Bates had a decision to make — stay in California, or make the cross-country trek to North Carolina.

Joann talked the situation over with her son and the two came to a harmonious decision. He would continue down the path that Mark Bates would have wanted him to take.

“Before [Mark] passed away, he had set up a path for Aaron to follow,” Joann said. “N.C. State was on that path, and he had to put things in motion and follow it.”

So Bates packed up his cleats with the rest of his life, and made the 2,800-mile shoot across I-40 towards Raleigh. The rest of the story is in the record books.

As Bates now digs his cleats into his second season of ACC baseball, he’s excited for a number of reasons about the year to come.

He’s excited to be surrounded by a team he loves and a community he embraces.

“The whole community around here has been amazing” Bates said. “I’ve never been part of something that so many people care about and support.”

Bates is also excited that his mother will finally get a chance to see him play for the Pack. She’s making her first trip to Raleigh in mid-March with her daughter, who has also applied to State.

Rarely has Joann seen Bates play without her husband alongside. Without him, she predicted her first game at Doak Field to be somewhat bittersweet.

But she knew she wouldn’t be alone watching the game for the same reason she knew her son wouldn’t be alone in North Carolina. His father, she said, has been beside him all along.

“I truly think his father has been right beside him at every single game, and I think he’s smiling the whole time,” Joann said. “He knows his son is exactly where he’s supposed to be, and that’s playing for N.C. State.”